Blog

Biosimilars 2022 Year in Review

Fish & Richardson

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

2022 heralded the next chapter for biosimilars in the United States, including U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of biosimilars in new therapeutic areas, additional interchangeable designations, and litigation relating to biosimilars of more recent biologics. Regulatory agencies and legislators also renewed their focus on access to lower-cost biologics, including biosimilars.

Here, we review the developments in 2022 in the biosimilar field, including FDA approvals, new biosimilar product launches, Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act and biosimilar-related antitrust litigation, post-grant challenges to biologic drug patents, and legislative and regulatory efforts implicating biosimilars.

Table of Contents

I. Biosimilar Approvals and Launches in 2022

III. Antitrust and Competition

IV. Post-Grant Challenges at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board

V. Biosimilar Regulatory Updates

VI. Legislation Affecting Biosimilars

I. Biosimilar Approvals and Launches in 2022

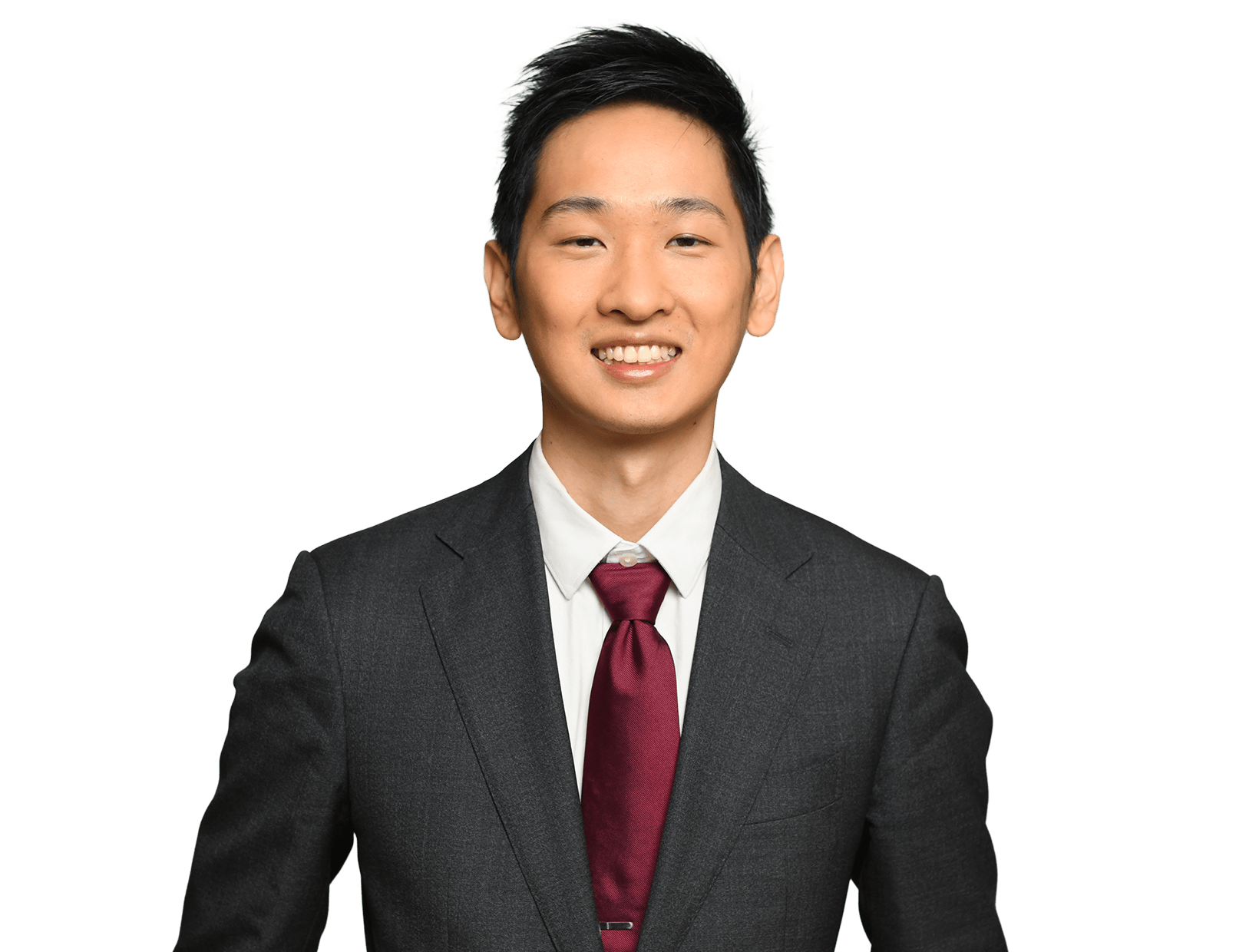

To date, FDA has approved 40 biosimilars, and 25 have launched in the U.S. (See Appendix A (summarizing publicly available information regarding biosimilars approved as of 2022)). While FDA approvals slowed significantly during the height of the global COVID-19 pandemic, approvals rebounded in 2022, with seven new biosimilar approvals. All seven biosimilars approved in 2022 referenced products with previously approved biosimilars; there were no biosimilars approved in 2022 referencing new reference products. 2022 also saw four new product launches, including the first two Lucentis® (ranibizumab) biosimilars.

Figure 1 below summarizes FDA biosimilar approvals and product launches in the U.S. from 2015 through 2022.

Figure 1. Biosimilar Approvals and Launches by Year

In 2022, FDA designated two new interchangeable biosimilars: Rezvoglar™ (referencing Lantus® (insulin glargine)) and Cimerli™ (referencing Lucentis® (ranibizumab)). This doubled the number of FDA-approved biosimilar products with an interchangeability designation, bringing the total number to four: two insulin products referencing Lantus®, an anti-inflammatory product referencing Humira®, and an ophthalmology product referencing Lucentis®. The FDA-approved biosimilars with interchangeable designations are summarized below in Table 1.

Table 1. Approved Biosimilars with Interchangeable Designation

| Biosimilar | Reference Product | Interchangeable Approval Date |

| Rezvoglar™ (Eli Lilly) |

Lantus® (Sanofi) |

November 16, 2022 |

| Cimerli™ (Coherus / Bioeq) |

Lucentis® (Roche / Genentech) |

August 2, 2022 |

| Cyltezo® (Boehringer Ingelheim) | Humira® (AbbVie) | October 15, 2021 |

| Semglee® (Mylan (Viatris) / Biocon) | Lantus® (Sanofi) |

July 28, 2021 |

Additional biosimilars remain in the pipeline. The number of development programs enrolled in FDA’s Biosimilar Biological Product Development Program—FDA’s program for expediting the process for the review of submissions in connection with biosimilar biological product development—has risen again. As of Q4 of Fiscal Year 2022, FDA reported 106 development programs participating in its BPD Program.

Table 2 summarizes publicly available information regarding select pending Biologics License Applications. The list includes biosimilars of new reference products, including Stelara® (ustekinumab), Actemra® (tocilizumab), and Tysabri® (natalizumab).

Table 2. Select Pending Biosimilar BLAs

| Proposed Biosimilar | Reference Product | Nonproprietary Name | FDA Status |

| AVT04 (Alvotech / Teva) |

Stelara® (Janssen) |

ustekinumab | BLA Accepted: January 2023 |

| BIIB800 (Biogen / Bio-Thera) |

Actemra® (Roche / Genentech) |

tocilizumab | BLA Accepted: December 2022 |

| MSB11456 (Fresenius Kabi) |

Actemra® (Roche / Genentech) |

tocilizumab |

BLA Accepted: August 2022 |

| PB006 (Sandoz / Polpharma) |

Tysabri® (Biogen) |

natalizumab | BLA Accepted: July 2022 |

| M710 (Mylan) |

Eylea® (Regeneron) |

aflibercept | BLA Accepted: December 2021 |

| EGI014 (Sandoz / EirGenix) |

Herceptin® (Roche / Genentech) |

trastuzumab | BLA Submitted: December 2021 |

| TX05 (Tanvex) |

Herceptin® (Roche / Genentech) |

trastuzumab | BLA Accepted: October 4, 2021 |

| Pegfilgrastim biosimilar (Lupin) | Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim | BLA Accepted: June 2, 2021 |

| BAT1706 (Bio-Thera) |

Avastin® (Roche / Genentech) |

bevacizumab | BLA Accepted: January 28, 2021 |

| AVT02 (Alvotech / Teva) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab | BLA Accepted: November 2020; delayed due to COVID-19 pandemic |

| TX01 (Tanvex) |

Neupogen® (Amgen) |

filgrastim |

BLA resubmitted: Nov. 22, 2020 Complete Response Letter reported May 2021 |

| MYL-1402O (Mylan / Biocon) |

Avastin® (Roche / Genentech) |

bevacizumab | BLA Accepted: March 2020 FDA Goal Date: December 27, 2020, but delayed due to COVID-19 pandemic |

| SB8 (Samsung Bioepis) |

Avastin® (Roche / Genentech) |

bevacizumab |

BLA Submitted: September 2019 |

In addition, more biosimilar product developers have initiated studies to support interchangeability or submitted applications to FDA seeking interchangeability status. For example, both Alvotech and Pfizer have announced that FDA accepted interchangeability applications for their respective Humira® biosimilars, AVT02 and Abrilada™. Celltrion has announced that it will pursue a Phase III clinical trial to support interchangeability of its Humira® biosimilar, Yuflyma®. And Samsung Bioepis and Amgen have announced that they will pursue interchangeability designations for their Humira® biosimilars, Hadlima® and Amjevita™, respectively. New launches and approvals of interchangeable biosimilars in other therapeutic categories are likely to follow.

Back to top ↑II. BPCIA Litigation

Below, we briefly summarize overall statistics regarding BPCIA District Court litigation to date, and in the subsequent sections, we review (a) ongoing BPCIA District Court cases, (b) BPCIA District Court cases that settled or resolved in 2022, and (c) non-BPCIA decisions that bear on biosimilars. Note that the Federal Circuit did not decide any BPCIA appeals in 2022, and there were no BPCIA appeals pending before the Federal Circuit at the end of 2022.

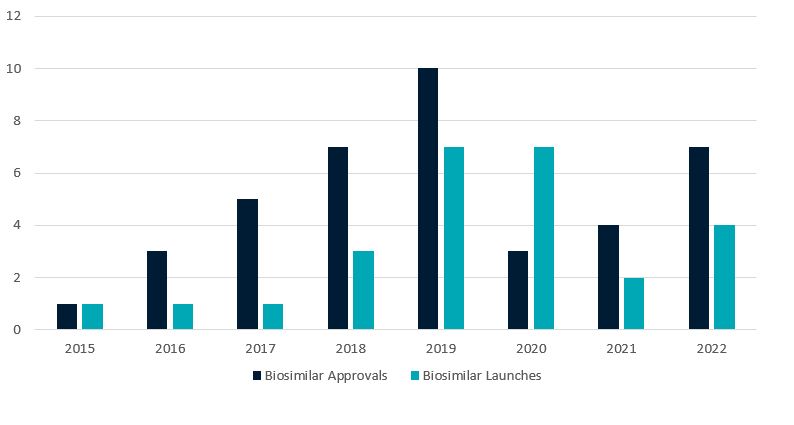

Since the BPCIA’s enactment in 2010, more than 50 BPCIA cases have been filed in District Courts. (See Figure 2.) Many of these cases involve the same parties and the same biosimilar products (e.g., an infringement action filed by a reference product sponsor and a declaratory judgment action filed by the accused biosimilar developer). Amgen and Genentech (with 16 cases each) are the most active plaintiffs in BPCIA litigation. Amgen is also the most common BPCIA defendant (with nine cases), while Celltrion and Sandoz (each defendant in seven cases) are not far behind. Janssen and AbbVie have also been active in BPCIA litigation with eight and six cases, respectively (Janssen as plaintiff in six cases and as declaratory judgment defendant in two cases, AbbVie as plaintiff in five cases and as declaratory judgment defendant in one case).

Figure 2. BPCIA Cases Filed by Year Since BPCIA Enactment

Prior to 2022, all BPCIA litigation involved biosimilars of the same nine different reference products: Remicade®, Neulasta®, Neupogen®, Avastin®, Herceptin®, Rituxan®, Humira®, Enbrel®, and Epogen®. These reference products had been on the market a relatively long time, and many were long past the twelve years of marketing exclusivity afforded by the BPCIA—for example, Epogen® was first FDA-approved in 1989, Neupogen® was first FDA-approved in 1991, and Remicade®, Herceptin®, Rituxan®, and Enbrel® were all FDA-approved in the 1997–1998 timeframe.

In 2022, a new wave of lawsuits were filed for more recent reference products, including, Tysabri® (first FDA-approved in 2004), Stelara® (first FDA-approved in 2009), and Eylea® (first FDA-approved in 2011). As discussed below, these newer reference products have introduced new issues in BPCIA litigation. We now turn to these new cases and other recent litigation activity.

A. Ongoing BPCIA District Court Litigation

Four new BPCIA cases were filed in 2022. Those four new cases make up all of the ongoing BPCIA litigation, as all of the cases filed prior to 2022 have been resolved. The ongoing cases are identified in Table 3.

Table 3. BPCIA Cases Filed in 2022

| Case Name | Court | Filing Date | Biosimilar at Issue | Reference Product at Issue | # Asserted Patents1 |

| Genentech v. Tanvex (3:22-cv-00809) |

S.D. Cal. | 6/2/2022 | TX05 |

Herceptin® |

3 |

|

Regeneron v. Mylan |

N.D. W. Va. | 8/2/2022 | M710 |

Eylea® |

24 |

|

Biogen v. Sandoz and Polpharma |

D. Del. | 9/9/2022 | PB006 |

Tysabri® |

28 |

|

Janssen v. Amgen (1:22-cv-01549) |

D. Del. | 11/29/2022 | ABP 654 |

Stelara® |

2 |

We discuss each briefly below.

Genentech v. Tanvex (22-cv-00809 S.D. Cal.)

This case involves Tanvex’s proposed biosimilar of Genentech’s Herceptin® (trastuzumab) called TX05. Tanvex is the fifth trastuzumab biosimilar developer against which Genentech has brought BPCIA litigation, following litigation against Pfizer, Celltrion/Teva, Amgen, and Samsung Bioepis, all of which settled between 2018 and 2020. In 2017, Genentech also reached a settlement with Mylan in relation to Genentech’s patents for trastuzumab, in which Mylan agreed to withdraw two inter partes review challenges. Each of these companies has commercially launched its trastuzumab biosimilar in the U.S. (See Appendix A, below.)

On June 2, 2022, Genentech filed a complaint against Tanvex, asserting U.S. Patent Nos. 8,574,869 (“the ’869 patent”), 10,662,237 (“the ’237 patent”), and 10,808,037 (“the ’037 patent”). (Dkt. 1 at ¶ 63.) These patents are directed to methods of manufacturing. (Id. at ¶¶ 64–66.) Genentech previously asserted both the ’237 and ’869 patents against various biosimilar companies. (See Dkt. 20 (Notice of Related Cases).) The ’037 patent had not been previously asserted.

The parties engaged in the patent dance and agreed to litigate these three patents in the first wave of litigation. (Dkt. 1 at ¶ 3; see also id. at ¶¶ 53–62.)

The initial pleadings raised themes common in BPCIA cases. For example, Genentech alleged deficiencies at each step of the patent dance, such as Tanvex’s alleged failure to provide “other” manufacturing information as required under 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(2)(A). (Id. at ¶¶ 54–56.) Genentech therefore claimed that Tanvex’s document productions “failed to fully describe Tanvex’s manufacturing process, such that Genentech was unable to evaluate many of Tanvex’s non-infringement arguments.” (Id. at ¶ 57.) Tanvex disputed that its productions under (2)(A) were deficient. (See, e.g., Dkt. 17 at ¶ 54.)

The parties also disputed whether Tanvex could raise invalidity theories in litigation that were not included in the patent dance statements, an issue that has been before the courts in several other cases. (E.g., Genentech v. Amgen, 17-cv-01407, 2020 WL 636439 (D. Del. Feb. 11, 2020); Genentech v. Samsung Bioepis (20-cv-00859 D. Del.);2 AbbVie v. Alvotech hf. (21-cv-02258 N.D. Ill.; 21-cv-02899 N.D. Ill.), discussed below.) Here, Genentech alleged that during the patent dance Tanvex “failed to provide any statements of invalidity … for any of the patents.” (Dkt. 1 at ¶ 58.) However, Tanvex’s counterclaims of invalidity, filed September 1, 2022, included exemplary invalidity theories and identified prior art. (See, e.g., Dkt. 17 at ¶¶ 33–34.) In answering the counterclaims, Genentech objected to Tanvex’s approach, claiming that “[w]here Tanvex could have, but did not, provide the required detailed statement on invalidity [during the patent dance], Tanvex has waived any invalidity arguments in future litigation or in an administrative proceeding based on information that was available when Tanvex served its contentions.” (Dkt. 32 at ¶ 31.)

Although a claim construction and tutorial hearing were scheduled for May 4, 2023 (Dkt. 41 at 3), the deadlines were vacated when the parties notified the court they had reached an agreement-in-principle to resolve their claims and expected to file a joint stipulation to dismiss sometime in January or early February 2023. (Dkt. 55; Dkt. 58.)

Regeneron v. Mylan (22-cv-00061 N.D. W. Va.)

On August 2, 2022, Regeneron filed a complaint against Mylan asserting infringement of 24 patents. (Dkt. 1.) The case relates to Mylan’s Eylea® (aflibercept) biosimilar called M710. This is the first BPCIA litigation filed in the Northern District of West Virginia, the first BPCIA litigation involving Regeneron, and the first BPCIA litigation involving a proposed biosimilar of Eylea® (aflibercept). Eylea® (first FDA-approved in 2011) is the newest biologic to be subject to BPCIA litigation, raising issues of first impression for the courts.

Regeneron’s complaint alleges that Mylan submitted its biosimilar BLA in October 2021, and the parties engaged in the patent dance from December 2021 through July 2022. (Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 3–5; see also id. at ¶¶ 18–22.) During the dance, Regeneron proposed litigating “a targeted subset of the listed patents,” but Mylan maintained that all 25 of the relevant listed patents should be included. (Id. at ¶ 21.) Thus, at the end of the patent dance, Regeneron filed suit on the full portfolio of patents. (Id.) Regeneron no longer asserted one of the patents against Mylan, so its complaint included 24 patents. (Id. at ¶ 22 & n.3.)

On August 5, 2022, Regeneron filed a motion requesting an expedited status conference “under Rule 40 and 28 U.S.C. § 1567 to position this case for trial no later than June 2023, so that Regeneron may avail itself of the relief provided by 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(4)(D).” (Dkt. 7 at 1.) The statutory provision of § 271(e)(4)(D) provides for an injunction when BPCIA exclusivities have not yet expired, a situation that did not arise in previous litigations involving older biologics. Specifically, § 271(e)(4)(D) states that for the artificial act of infringement of filing a biosimilar BLA:

the court shall order a permanent injunction prohibiting any infringement of the patent by the biological product involved in the infringement until a date which is not earlier than the date of the expiration of the patent that has been infringed under paragraph (2)(C), provided the patent is the subject of a final court decision, as defined in section 351(k)(6) of the Public Health Service Act, in an action for infringement of the patent under section 351(l)(6) of such Act, and the biological product has not yet been approved because of section 351(k)(7) of such Act.

(Emphasis added.) Regeneron explained that this statutory permanent injunction “requires resolving the parties’ disputes through final judgment and appeal before the date on which FDA may approve the biosimilar product for marketing.” (Dkt. 7 at 1 (bold emphasis added).) Regeneron alleged that its marketing exclusivity and additional pediatric exclusivity will run through May 2024. (Id. at 1, 5.) Regeneron therefore asked for trial in June 2023 (either on a subset of patents or all patents), so that any appeals could be exhausted by May 2024 and the statutory injunction could be available. (Id. at 5–6.) Regeneron also acknowledged the novel questions presented by this case, alleging that “[t]his is the first biosimilar patent case that will proceed while the innovator product’s regulatory exclusivity remains in place.” (Dkt. 41 at 5.) Mylan opposed the motion. (Dkt. 26.)

On October 25, 2022, at Regeneron’s request, the court entered a scheduling order proceeding on a subset of patents with a trial scheduled for June 2023. (Dkt. 87 at 1–2.) As required by the court, Regeneron identified six patents from three patent families for these initial proceedings. (Dkt. 88.) According to Regeneron, the six patents include: one patent covering the “drug product” (specifically “the actual solution in a vial that maintains the drug’s stability for months”), two patents directed to the use of aflibercept (specifically “how much and how often the drug should be administered to permit more time between doses than patients enjoyed with previous treatments while achieving therapeutic gains”), and three patents concerning “methods for making aflibercept.” (Dkt. 124 at 1.) Regeneron will need to narrow its patent selection down to no more than three patents and 25 claims before the June trial. (Dkt. 87 at 2.) Regeneron also stipulated that “it will not seek injunctive relief on the other 18 patents asserted in its Complaint (ECF 1) with respect to the United States marketing or sales of Mylan’s current aBLA Product (BLA No. 761274).” (Id. at 1 (emphasis omitted).)

On December 9, 2022, Mylan filed a motion for leave to amend its answer, defenses, and counterclaims to add a declaratory judgment counterclaim of no lost profits or injunctive relief with respect to the patents that Regeneron did not select to proceed in the first stage of litigation. (Dkt. 164 at 1–2.) Mylan alleged that Regeneron had “effectively dismisse[d] those [18 other] patents without prejudice from the (l)(6) suit” and was therefore limited to a “reasonable royalty” pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(6)(B). (Dkt. 163-1 at ¶¶ 216, 226.) The court has not yet ruled on the motion.

On December 16, 2022, Regeneron filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings as to Mylan’s inequitable conduct defenses and counterclaims. (Dkt. 176 at 1.) Regeneron argued that (1) Mylan failed to plead any of its theories of inequitable conduct with particularity; (2) any non-disclosure of materials to the United States Patent and Trademark Office in earlier applications was cured because Regeneron later disclosed those materials when applying for the relevant patents-at-issue; and (3) the “purported misrepresentations [to USPTO] Mylan cites were not material assertions of fact but mere attorney argument, which cannot form the basis of an inequitable conduct claim or defense.” (Id. at 2–3.) Mylan filed a motion for extension of time to file its response until January 13, 2023 (Dkt. 189), which Regeneron did not oppose (Dkt. 196), and the court granted (Dkt. 198).

A Markman hearing is scheduled for January 24, 2023, and a trial is scheduled for June 12, 2023. (Dkt. 87 at 2; Dkt. 209.)

Biogen v. Sandoz and Polpharma (22-cv-01190 D. Del.)

Biogen filed a sealed complaint against Sandoz and Polpharma on September 9, 2022, related to the defendants’ Tysabri® (natalizumab) biosimilar PB006. (Dkt. 2, 10 (redacted version).) Biogen’s complaint asserted 28 patents relating to natalizumab and associated manufacturing and testing methods. (Dkt. 10 at ¶¶ 2, 4, 112–167.) This is the first BPCIA litigation involving Biogen as the reference product sponsor, the first BPCIA litigation involving Polpharma, and the first BPCIA litigation involving a proposed biosimilar of Tysabri® (natalizumab).

The heavily redacted filings suggest that the parties engaged in some steps of the patent dance, but did not complete the entire process. According to the complaint, Sandoz announced that FDA accepted the biosimilar BLA on July 25, 2022. (Id. at ¶ 27.) Sandoz provided some confidential information to Biogen, but refused Biogen’s requests for any additional information. (Id. at ¶¶ 103–104.) Biogen served a (3)(A) patent list, but Sandoz declined to participate in any other steps of the patent dance. (Id. at ¶¶ 105–107.) Biogen therefore was entitled to file a declaratory judgment complaint under 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(9)(B). (Id. at ¶ 108.)

On October 5, 2022, Sandoz filed an answer, affirmative defenses, and counterclaims. (Dkt. 14, 19 (redacted version).) Sandoz counterclaimed for invalidity of each of the 28 asserted patents. (Dkt. 19 at Counterclaims.) On October 26, 2022, Biogen moved to dismiss Sandoz’s counterclaims of invalidity under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) for failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. (Dkt. 29.) Biogen alleged that “Sandoz’s counterclaims of invalidity are merely threadbare legal conclusions devoid of any supporting factual allegations.” (Id. at 1.) The motion to dismiss was subsequently mooted because, on December 1, 2022, Biogen filed a first amended complaint, reducing the number of asserted patents from 28 to 17. (Dkt. 51, 56 (redacted version).) Sandoz answered the amended complaint on January 4, 2023. (Dkt. 63, 68 (redacted version).)

As of mid-November 2022, Biogen had not yet served Polpharma, a Polish company, with the original or amended complaint. On October 19, 2022, Biogen filed a motion for alternative service, seeking “entry of an order pursuant to Federal Rule Civil Procedure 4(f)(3), authorizing alternative service on Polpharma” by email to U.S. counsel. (Dkt. 30 at 1; see also Dkt. 24.) Sandoz opposed the motion. (Dkt. 34, 37 (redacted version).) The court has not yet ruled on Biogen’s motion for alternative service.

On October 14, 2022, Biogen and Sandoz filed a joint stipulation and scheduling order for expedited preliminary injunction proceedings. (Dkt. 20, 22 (redacted version).) According to a letter from Biogen’s counsel, Biogen “intend[s] to seek a preliminary injunction in advance of the launch of defendants’ biosimilar product.” (Dkt. 27; see also Dkt. 21.) The court entered a sealed order on October 20, 2022. (Dkt. 26.) According to publicly available information, Biogen needed to elect up to five patents and 10 claims for the preliminary injunction proceedings by November 2022. (Dkt. 22 at 2–3.) Briefing on Biogen’s motion for preliminary injunction is scheduled to be completed by April 2023, and a preliminary injunction hearing is to be scheduled thereafter. (Id. at 3.)

Janssen v. Amgen (22-cv-01549 D. Del.)

Janssen filed a complaint against Amgen on November 29, 2022, alleging infringement of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,902,734 (“the ’734 patent”) and 10,961,307 (“the ’307 patent”). (Dkt. 1 at ¶ 5.) The ’734 patent covers ustekinumab, and the ’307 patent covers methods of treating ulcerative colitis with ustekinumab. (Id.) This is the first BPCIA litigation involving a proposed biosimilar of Stelara® (ustekinumab).

The parties did not engage in the patent dance. According to the complaint, on November 7, 2022, “Amgen informed Janssen of its intention, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(8)(A), to begin marketing its biosimilar version of STELARA® in 180 days (i.e., on May 6, 2023) or immediately upon receiving FDA approval thereafter.” (Id. at ¶ 4.) “Amgen further stated that it intends to market ABP 654 for all indications for which STELARA® is approved.” (Id.) On November 11, 2022, “counsel for Janssen asked Amgen’s counsel whether Amgen had filed its aBLA with FDA, whether and when FDA had accepted Amgen’s aBLA application, whether Amgen intends to participate in the BPCIA ‘patent dance,’ and whether Amgen would provide its aBLA to Janssen.” (Id. at ¶ 25.) According to the complaint, “Amgen refused to disclose when it filed its aBLA, whether the FDA has accepted it, whether Amgen intends to participate in the BPCIA ‘patent dance,’ or whether the BPCIA’s deadline by which Amgen must provide Janssen with a copy of its aBLA has passed.” (Id.) “Amgen also refused to provide Janssen with either a copy of its aBLA or any other requested information.” (Id.) As of the filing of the complaint, FDA had not yet approved Amgen’s proposed ABP 654 biosimilar product. (Id. at ¶ 23.)

On December 20, 2022, the parties filed a joint stipulation to extend the deadline for Amgen to move, answer, or otherwise respond to the complaint through and including January 23, 2023. (Dkt. 8.) On the same day, the court ordered the extension.

B. BPCIA Litigation Settled or Resolved in 2022

BPCIA cases settled or otherwise resolved in 2022 include:

- Amgen v. Hospira (20-cv-00201 D. Del.); Neulasta®/Nyvepria™

- Genentech v. Samsung Bioepis (20-cv-00859 D. Del.); Avastin®/SB8

- AbbVie v. Alvotech hf. (21-cv-02258 N.D. Ill.); Humira®/AVT02

- AbbVie v. Alvotech hf. (21-cv-02899 N.D. Ill.); Humira®/AVT02

We discuss each of these resolved cases briefly below.

Amgen v. Hospira (20-cv-00201 D. Del.)

This case involved Hospira’s biosimilar of Amgen’s Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim). Amgen filed a complaint against Hospira and Pfizer on February 11, 2020, asserting U.S. Patent No. 8,273,707 (“the ’707 patent”), which is directed to methods of protein purification requiring a certain combination of salts at certain concentrations. (Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 8, 54, 61–62.) Amgen previously asserted this patent in BPCIA litigation against two other biosimilar developers, Coherus and Mylan, and both of those cases were resolved in 2019.

Before the case was dismissed, the court issued several orders. First, the court denied a motion to dismiss brought by Hospira and Pfizer. The defendants had argued that prosecution history disclaimer and estoppel precluded infringement for the same reasons as the Coherus decision. (Dkt. 19 at 1–4.) The court also construed a disputed term, leading Amgen to confirm it would only seek a finding of infringement under the doctrine of equivalents, not literal infringement. (Dkt. 75 at 1.)

Hospira and Pfizer had also filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement, arguing that there was no infringement under the doctrine of equivalents because the accused manufacturing process uses a “low” salt concentration below the claimed “intermediate” range. (Dkt. 84 at 7–8.) Amgen responded that genuine disputes of material fact precluded summary judgment. (Dkt. 91 at 2.) While fully briefed, the court did not rule on the motion.

On March 18, 2022, the parties filed a stipulation and order of dismissal with prejudice, stipulating and agreeing that all claims and counterclaims between the parties in this action be dismissed with prejudice, with each party to bear its own costs, expenses, and attorneys’ fees. (Dkt. 100.) On March 21, 2022, the court ordered the dismissal.

Genentech v. Samsung Bioepis (20-cv-00859 D. Del.)

This case involved Samsung Bioepis’s proposed biosimilar of Genentech’s Avastin® (bevacizumab). Genentech filed a complaint against Samsung Bioepis on June 28, 2020, alleging infringement of 14 patents covering methods of manufacturing bevacizumab and methods of treating patients with bevacizumab. (Dkt. 1.) Samsung Bioepis is the third bevacizumab biosimilar developer against which Genentech has initiated BPCIA litigation, following litigation against Pfizer and Amgen, which settled in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Except for one discrete issue related to a protective order dispute, the case had been stayed since February 2021.

On September 7, 2022, the parties filed a joint stipulation of dismissal, stating that the parties had “entered into a Bevacizumab Settlement Agreement, and mutually agree[d] to voluntarily dismiss all claims and counterclaims asserted in [this] case with prejudice.” (Dkt. 72 at 1.) The parties stipulated that “[i]n the event Genentech files a patent infringement action based on the asserted patents of [this] case against Samsung [Bioepis], nothing in this Order shall prevent Samsung [Bioepis] from challenging the validity, noninfringement, or enforceability of any of the asserted patents in such action.” (Id. at 2.) On September 8, 2022, the court ordered the dismissal. (Dkt. 73.)

AbbVie v. Alvotech hf. (21-cv-02258 N.D. Ill.; 21-cv-02899 N.D. Ill.)

These cases involved Alvotech’s AVT02, a proposed biosimilar of AbbVie’s high-concentration (100 mg/mL) Humira® (adalimumab). On April 27, 2021, AbbVie filed a complaint against Alvotech hf., alleging infringement of the four patents that resulted from the patent dance. (‑2258 Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 61–62.) This was the first BPCIA litigation filed in the Northern District of Illinois, but the fourth BPCIA litigation brought by AbbVie against an adalimumab biosimilar manufacturer following litigation against Amgen, Sandoz, and Boehringer Ingelheim, which settled in 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively.

On May 28, 2021, AbbVie filed another suit (the ‑2899 case) against Alvotech hf. In its complaint, AbbVie stated that Alvotech USA’s Notice of Commercial Marketing triggered AbbVie’s ability to file suit on all patents identified in AbbVie’s (3)(A) list during the patent dance. (‑2899 Dkt. 1 at ¶ 17.) AbbVie initially asserted 58 additional patents, but subsequently amended its complaint twice to add newly issued patents. (‑2899 Dkt. 77, 130.)

On September 20, 2021, the court ordered a trial on 10 patents (three from the ‑2258 case and seven from the ‑2899 case) starting on August 1, 2022 (about 16 months after the initial -2258 complaint was filed). (‑2258 Dkt. 63; see also ‑2258 Dkt. 54.) The court stated it planned to issue a trial decision by the end of October 2022, and, “[i]n light of that, [Alvotech] agreed not to launch AVT02 in the United States prior to the issuance of the Court’s decision.” (‑2258 Dkt. 63 at 4.) The 10 patents spanned technologies including autoinjector devices, methods of treatment, antibody purification, and pharmaceutical formulations.

Before the cases were dismissed, the court denied two motions to dismiss brought by Alvotech hf.:

- On June 2, 2021, Alvotech hf. filed a motion to dismiss the ‑2258 case, arguing, inter alia, that: (1) the court lacked subject matter jurisdiction and the complaint did not state a claim under the BPCIA because AbbVie failed to sue Alvotech USA, the subsection (k) applicant for the AVT02 biosimilar at issue (and instead sued Alvotech USA’s Icelandic parent company, Alvotech hf.); (2) AbbVie’s complaint failed to name a necessary party, Alvotech USA; and (3) AbbVie’s complaint should be dismissed for lack of personal jurisdiction over Alvotech hf. (‑2258 Dkt. 27.) In opposition, AbbVie argued that (1) Alvotech hf. was a proper defendant because it was the “submitter” of the AVT02 BLA; (2) Alvotech USA was not a necessary party to the litigation; and (3) the court had personal jurisdiction over Alvotech hf. (‑2258 Dkt. 31.) On August 23, 2021, the court denied Alvotech hf.’s motion to dismiss, finding that (1) “Abbvie’s complaint adequately alleges that Alvotech hf. is a ‘submit[ter]’ of the aBLA within the meaning of 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2)(C)”; (2) “Alvotech hf. [] failed to meet its burden of establishing that this case must be dismissed for failing to join Alvotech USA”; and (3) the court has specific jurisdiction “because the aBLA submission indicates Alvotech hf.’s intent to market and distribute its biosimilar drug in Illinois.” AbbVie Inc. v. Alvotech hf., 21-cv-02258, 2021 WL 3737733, at *9–12 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 23, 2021).

- On July 29, 2021, Alvotech hf. filed a motion to dismiss the ‑2899 case pursuant to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1)–(2) and (6)–(7). (‑2289 Dkt. 29.) Alvotech hf. renewed its motion on December 3 and 29, 2021. (‑2289 Dkt. 91, 138.) Alvotech hf. argued, inter alia, that the BPCIA does not provide for “1) simultaneously filing claims under both 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2) and the Declaratory Judgment Act in a ‘second phase’ case; and 2) asserting ‘second phase’ claims against a party that neither provided a notice of commercial marketing under the BPCIA nor applied for approval for the contested biosimilar drug.” (‑2289 Dkt. 29 at 1.) Alvotech hf. argued that “the BPCIA provides no basis for claims under § 271(e)(2)(C) in this second phase,” and instead “requires the second phase suit to be one for declaratory judgment to determine potential future infringement.” ( at 1, 4.) In opposition, AbbVie argued, inter alia, that the BPCIA does not limit phase two to declaratory judgment actions. (‑2289 Dkt. 43 at 3–4.) The parties debated whether allowing 271(e) causes of action for second phase litigation would disrupt the structure of the BPCIA in future cases. (See, e.g., ‑2289 Dkt. 45 at 2 (alleging that AbbVie’s approach would “vitiate the clear two-phase structure that Congress created in the BPCIA”); ‑2289 Dkt. 43 at 5 (AbbVie responding that “Alvotech’s ‘doomsday’ scenario is … specious.”).) On January 26, 2022, the court denied Alvotech hf.’s motion to dismiss, finding that AbbVie could bring infringement claims under § 271(e)(2)(C)(i) during the second phase of litigation. AbbVie Inc. v. Alvotech hf., 582 F. Supp. 3d 584 (N.D. Ill. 2022). The court also rejected Alvotech hf.’s reading of the BPCIA that would “preclude the RPS from seeking injunctive relief pursuant to § 271(e)(4) during the second phase and limit[] second phase relief to a declaratory judgment and preliminary injunctive relief.” (Id. at 591.)

Numerous other issues had been briefed, but remained undecided when the litigations were dismissed. For example, on February 18, 2022, AbbVie filed a motion to strike Alvotech hf.’s final invalidity and unenforceability contentions in both cases, arguing that the court should strike, inter alia, contentions that were not included in Alvotech hf.’s patent dance disclosures, initial contentions, or “unenforceability claims and defenses pleaded in [its] two answers.” (‑2258 Dkt. 256 at 1–2; ‑2899 Dkt. 242 at 1–2.) In opposition, Alvotech hf. argued, inter alia, that it was “permitted to raise additional prior art and arguments from those contained in the initial contentions and patent dance.” (‑2258 Dkt. 262 at 3–4; ‑2899 Dkt. 250 at 3–4.) In support, Alvotech hf. cited Genentech v. Amgen, 17-cv-01407, 2020 WL 636439 (D. Del. Feb. 11, 2020), where the court found that a biosimilar applicant is not precluded from raising a defense not disclosed during the patent dance. (‑2258 Dkt. 262 at 4; ‑2899 Dkt. 250 at 4.)

On March 9, 2022, the parties filed a joint stipulation of dismissal, dismissing all claims, affirmative defenses, and counterclaims in both actions without prejudice, with each party to bear its own attorneys’ fees and costs. (‑2258 Dkt. 276; ‑2899 Dkt. 262.) The court entered the dismissal on the same day. (‑2258 Dkt. 278; ‑2899 Dkt. 264.) AbbVie announced that it “resolved all U.S. HUMIRA (adalimumab) litigation with Alvotech,” and “[u]nder the terms of the resolution, AbbVie will grant Alvotech a non-exclusive license to its HUMIRA-related patents in the United States, which will begin on July 1, 2023.”

C. Section 112 Issues at the Supreme Court

This year, the Supreme Court granted a petition for writ of certiorari to consider the standard for enablement under 35 U.S.C. § 112 in a dispute related to antibodies. Although not a BPCIA decision, this case may have implications in the biosimilars context.

The Supreme Court will be reviewing the Federal Circuit’s decision in Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, Aventisub LLC, 987 F.3d 1080 (Fed. Cir. 2021), addressing the § 112 enablement requirement. The case involves Amgen’s Repatha® (evolocumab), an antibody product for treating high cholesterol. The Federal Circuit held that functionally defined claims covering a genus of antibodies were not enabled because undue experimentation would be required to practice the full scope of the claims. Id. at 1088. The relevant claims defined the claimed antibodies by their function: “binding to a combinations of sites (residues) on the PCSK9 protein, in a range from one residue to all of them; and blocking the PCSK9/LDLR interaction.” Id. at 1083. The court explained that functional limitations “pose high hurdles in fulfilling the enablement requirement for claims with broad functional language.” Id. at 1087. The court also concluded that the functional limitations here were “broad,” “the disclosed examples and guidance [were] narrow,” the invention was “in an unpredictable field of science with respect to satisfying the full scope of the functional limitations,” and “no reasonable jury could conclude under these facts that anything but ‘substantial time and effort’ would be required to reach the full scope of claimed embodiments.” Id. at 1087–88.

On June 21, 2021, the court denied Amgen’s petition for panel rehearing or rehearing en banc. Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, Aventisub LLC, 850 F. App’x 794 (Mem) (Fed. Cir. 2021). Judge Lourie, joined by Judges Prost and Hughes, authored a separate opinion on the denial of the petition for panel rehearing to reject Amgen’s argument that the court created a new test for enablement. Id.

On November 18, 2021, Amgen filed a petition for a writ of certiorari, presenting the following questions:

- Whether enablement is “a question of fact to be determined by the jury,” Wood v. Underhill,46 U.S. (5 How.) 1, 4 (1846), as this Court has held, or “a question of law that [the court] review[s] without deference,” Pet. App. 6a, as the Federal Circuit holds.

- Whether enablement is governed by the statutory requirement that the specification teach those skilled in the art to “make and use” the claimed invention, 35 U.S.C. § 112, or whether it must instead enable those skilled in the art “to reach the full scope of claimed embodiments” without undue experimentation-i.e., to cumulatively identify and make all or nearly all embodiments of the invention without substantial “‘time and effort,”’ Pet. App. 14a (emphasis added).

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, Aventisub LLC, No. 21-757, 2021 WL 5506421 (U.S. Nov. 18, 2021).

On November 4, 2022, the Supreme Court granted the petition for a writ of certiorari limited to Question 2. Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, 143 S. Ct. 399 (Mem) (2022). Amgen’s brief on the merits was filed December 27, 2022. Amgen argued that (1) “the Federal Circuit’s reach-the-full-scope standard defies text, precedent, history, and policy”; (2) “the statutory ‘make and use’ standard should govern”; and (3) Amgen’s patents are enabled. (Brief at iii–iv.) On January 3, 2023, 14 amicus briefs were filed, and the Chemistry and the Law Division of the American Chemical Society moved for leave to participate in oral argument in support of Amgen. Amgen opposes the motion. Sanofi’s brief on the merits is due February 3, 2023.

While the Supreme Court has taken up the issue of enablement, the Court has declined invitations to review § 112 written description this term. In August 2021, the Federal Circuit issued a decision in Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc., 10 F.4th 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2021), addressing written description. The case involves chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies. The Federal Circuit reversed a jury award of over $1.2 billion because the jury’s written description verdict was not supported by substantial evidence. Id. at 1332. The claims at issue were genus claims that used functional language (binding function of single-chain antibody variable fragments (scFvs), a part of the CAR that determines what target molecule or antigen the CAR can recognize and bind to). Id. at 1333–34, 1335. The Federal Circuit pointed out that the specification identified only two exemplary scFvs for two different targets, which “[did] not provide information sufficient to establish that a skilled artisan would understand how to identify the species of scFvs capable of binding to the limitless number of targets as the claims require.” Id. at 1337. Further, “[e]ven accepting that scFvs were known and that they were known to bind, the specification provides no means of distinguishing which scFvs will bind to which targets.” Id. at 1338. The court also found that the specification “[did] not disclose structural features common to the members of the genus to support that the inventors possessed the claimed invention,” for example those structural features that distinguish between scFvs that bind and those at do not. Id. at 1338–39, 1342. On January 14, 2022, the court denied Juno’s petition for panel rehearing or rehearing en banc (No. 2020-1758). On November 7, 2022, the Supreme Court denied Juno’s petition for a writ of certiorari. Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc., 143 S. Ct. 402 (Mem) (2022). On November 23, 2022, Juno filed a petition for rehearing at the Supreme Court, arguing:

These two cases [Juno v. Kite and Amgen v. Sanofi] involve the very same sentence of the very same statute, 35 U.S.C. § 112(a). Both ask whether the “make and use” language from the statute provides the proper statutory test, and both ask whether the Federal Circuit’s addition of a “full scope” requirement is an appropriate addition to Congress’s language choice. The issues presented are tightly related, and the outcome in Amgen is likely to at least affect, if not be outcome-determinative of, this case.

Motion at 2. Juno therefore requested that “the Court grant rehearing of its order denying the petition for certiorari, vacate that order, and hold this case in abeyance pending the resolution of Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi.” Id. at 8. The Supreme Court denied Juno’s motion on January 9, 2023. Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc., No. 21-1566, 2023 WL 124509 (Mem) (U.S. Jan. 9, 2023).

Back to top ↑III. Antitrust and Competition

Humira®: Patent Thickets and Pay-for-Delay Settlements

In 2022, the Seventh Circuit affirmed the dismissal of an antitrust case brought against AbbVie related its practices surrounding Humira® (adalimumab), one of the highest grossing biologics. The Seventh Circuit’s decision struck a blow to antitrust claims based on “patent thickets” and novel “pay-for-delay” theories. It also appeared to endorse—or at least not deter—a patent prosecution strategy based on obtaining large numbers of patents to deter competition.

In June 2020, U.S. District Judge Manish Shah dismissed a complaint brought by indirect purchasers of Humira® (adalimumab) against AbbVie alleging federal antitrust violations based on two theories: (1) that AbbVie had constructed an anticompetitive “thicket” of weak patents and (2) that AbbVie had entered into anticompetitive pay-for-delay agreements with adalimumab biosimilar manufacturers by allowing earlier entry in Europe in exchange for staying off the market in the United States until 2023. In re Humira (Adalimumab) Antitrust Litig., 465 F. Supp. 3d 811 (N.D. Ill. 2020).

On August 1, 2022, a Seventh Circuit panel affirmed the district court’s dismissal. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. AbbVie Inc., 42 F.4th 709 (7th Cir. 2022).

The Seventh Circuit rejected the plaintiffs’ patent “thicket” theory based on the sheer number of AbbVie’s patents:

But what’s wrong with having lots of patents? If AbbVie made 132 inventions, why can’t it hold 132 patents? The patent laws do not set a cap on the number of patents any one person can hold—in general, or pertaining to a single subject. Tech companies such as Cisco, Qualcomm, Intel, Microsoft, and Apple have much larger portfolios of patents. Thomas Edison alone held 1,093 U.S. patents.

Id. at 712 (internal citation omitted). The panel was also unconvinced by the argument that AbbVie’s patents were too weak to monopolize the sales of such an important drug, holding: “[w]eak patents are valid; to say they are weak is to say that their scope is limited, not that they are illegitimate.” Id. at 713.

Lastly, the panel held the challenged settlement agreements were lawful. AbbVie agreed in each agreement to biosimilar entry in each geographical region (Europe and the U.S.) before the last patents expired in that region. AbbVie also did not pay anyone to delay entry. The panel noted that the district judge saw this as “0 + 0 = 0” and concluded “[w]e see this the same way.” Id. at 715.

Outside of the courts, lawmakers and regulators have also continued to raise concerns about patent thickets. In a letter dated May 25, 2022, a bipartisan pair of Senators asked USPTO and FDA questions about how the agencies coordinate and review patent applications related to small-molecule drugs and biologics. The Senators’ letter was prompted by their belief that “[d]rug manufacturers are increasingly relying on patent thickets—dense webs of overlapping patents protecting a single drug—to evade competition.” On June 8, 2022, a different bipartisan group of Senators sent a second letter to USPTO Director Katherine Vidal, expressly urging USPTO to take action on patent thickets, defined as “large numbers of patents that cover a single product or minor variations on a single product.” The Senators quoted a statement from President Biden that patent thickets “have been misused to inhibit or delay—for years and even decades—competition from generic drugs and biosimilars, denying Americans access to lower-cost drugs.” The letter requested that USPTO issue a notice of proposed rulemaking or public request for comments based on certain questions directed to issues concerning terminal disclaimers, obviousness-type double patenting, and examination requirements for continuation patent applications.

Remicade® and Praluent®/Repatha®: Anticompetitive Exclusionary Contracts

In 2022, Johnson & Johnson and Janssen reached a proposed settlement for $25 million in a class action lawsuit relating to Remicade® (infliximab) brought by consumers and third-party payors. The litigation, In re Remicade Antitrust Litigation, No. 2:17-cv-04326-KSM (E.D. Pa.), was brought over four years ago and alleged that Johnson & Johnson and Janssen violated federal and state antitrust and consumer-protection laws by engaging in anticompetitive devices, such as “a web of exclusionary contracts” (Dkt. 1 at 1), to block competition by lower-cost biosimilar competitors in the infliximab market. The Pennsylvania court has tentatively approved the proposed settlement and has scheduled a Fairness Hearing for February 27, 2023.

Anticompetitive exclusionary contracts related to biologics have cropped up in other contexts as well in 2022. For example, on May 27, 2022, Regeneron filed an antitrust lawsuit against Amgen in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware alleging that Amgen used an “unlawful, anticompetitive bundling scheme” and “substantial rebates on entirely unrelated medications in Amgen’s portfolios” to protect Amgen’s Repatha® (evolocumab) product and deprive patients of the benefits of Regeneron’s cholesterol-reducing medication Praluent® (alirocumab). (1:22-cv-00697 D. Del., Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 1–4.) Amgen has moved to dismiss and stay the case. (Dkt. 17, 27.) While not a biosimilar case, this dispute could shed light on acceptable practices in the biologics and biosimilars space.

Relatedly, on June 16, 2022, the Federal Trade Commission issued a policy statement on “Rebates and Fees in Exchange for Excluding Lower-Cost Drug Products” to “explain its enforcement policy” with respect to these practices. FTC noted that “rebates and fees may shift costs and misalign incentives in a way that ultimately increases patients’ costs and stifles competition from lower-cost drugs, especially when generics and biosimilars are excluded or disfavored on formularies,” highlighting the example of insulin. FTC stated that it intends to closely scrutinize the impact of rebates and fees on patients and payers to determine whether the antitrust laws have been violated and monitor private litigation and file amicus briefs to aid courts in analyzing unlawful conduct that may raise drug prices.

Also in June 2022, FTC, citing “the urgent problems Americans have encountered in accessing and paying for insulin, among other drugs,” authorized, after a 5-0 vote, initiation of a study of the contracting practices of Pharmacy Benefit Managers “to evaluate whether and how PBMs contribute to competitive distortions in pharmaceutical markets.” FTC described PBMs as “unavoidable intermediaries in U.S. pharmaceutical markets” who “contract on behalf of payers—including employers and health insurance companies—with pharmacies and drug manufacturers.”

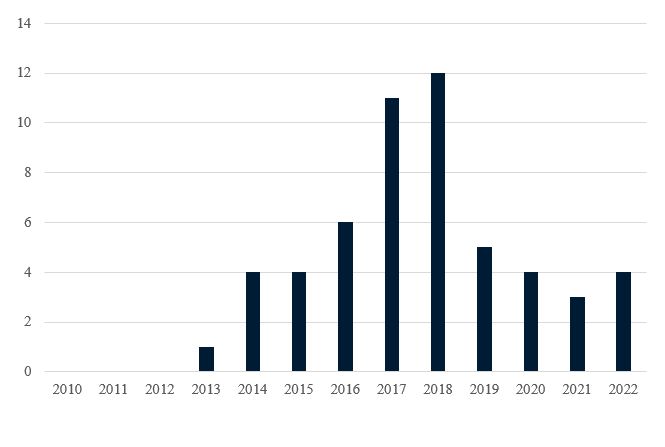

IV. Post-Grant Challenges at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board

Biologic and biosimilar activity at the PTAB in 2022 stayed roughly in line compared to filings in 2021. 18 IPR petitions and five post-grant review petitions were filed in 2021.3 Similarly, in 2022, 15 IPR and two PGR biologic petitions were filed, returning PTAB filings to pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 3. Biologic IPR Petitions by Year

We review exemplary filings and developments below.

- Actemra® (tocilizumab): In October 2022, Fresenius Kabi and Chugai Seiyaku Kabushiki Kaisha settled seven challenges against six patents generally directed to methods for treating interleukin-6 (IL-6) related diseases. (IPR2021-01024, -01025, -01288, -01336, -01542; IPR2022-00201, -01065.) At the time of settlement, the PTAB had instituted six of the challenges and one was pending institution. Separately, Celltrion filed IPRs challenging two of the same patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 8,580,264 and 10,874,677. (IPR2022-00578, -00579.) Patent Owner waived its preliminary responses, and the PTAB instituted both challenges on August 31, 2022.

- Emgality® (galcanezumab-gnlm) / Ajovy® (fremanezumab-vfrm): In March 2022, Eli Lilly filed two IPRs against Teva concerning U.S. Patent Nos. 11,028,160 and 11,028,161, directed to methods of treating or preventing refractory migraine with anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody, which Teva had asserted against Eli Lilly in pending District Court litigation over Eli Lilly’s Emgality® product (1:21-cv-10954 D. Mass.). (IPR2022-00738, -00739.) The PTAB granted institution in September 2022, and the related litigation has been stayed pending the PTAB’s final written decisions. (1:21-cv-10954 D. Mass., Dkt. 61.) In April 2022, Eli Lilly filed a third IPR against a Teva patent not currently asserted in the District Court litigation, U.S. Patent No. 10,392,434 (the “’434 patent”). (IPR2022-00796.) The ’434 patent is directed to methods of treating migraine with CGRP monoclonal antibody. The PTAB granted institution in October 2022. These recent challenges follow a previous round of PTAB challenges brought by Eli Lilly against Teva in 2018 over nine other patents related to Ajovy® and Emgality® in connection with a separate litigation (1:18-cv-12029 D. Mass.). The PTAB found six of the Ajovy® patents obvious over the prior art and the remaining three not invalid. These findings were upheld by the Federal Circuit on appeal. Eli Lilly & Co. v. Teva Pharms. Int’l GmbH, 8 F.4th 1331 (Fed. Cir. 2021); Teva Pharms. Int’l GmbH v. Eli Lilly & Co., 8 F.4th 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2021); Teva Pharms. Int’l GmbH v. Eli Lilly & Co., 856 F. App’x 312 (Fed. Cir. 2021). In November 2022, a jury found that Eli Lilly willfully infringed the remaining three patents, and awarded damages to Teva of $176.5 million. (1:18-cv-12029 D. Mass., Dkt. 593.) Post-trial briefing has been scheduled. (Dkt. 637.)

- Yervoy® (ipilimumab) / Keytruda® (pembrolizumab) / Opdivo® (nivolumab): In November 2022, Replimune Ltd. / Replimune, Inc. filed an IPR challenging Amgen’s U.S. Patent No. 10,034,938, directed to methods of treating late stage melanoma with an anti-PD-1 antibody or anti-CTLA-4 antibody. (IPR2023-00106.) An institution decision is expected in May 2023.

- Tysabri® (natalizumab): In July 2022, Sandoz filed a PGR petition challenging Biogen’s U.S. Patent No. 11,292,845 (the “’845 patent”), directed to a method of treating a patient with an inflammatory or autoimmune disease by monitoring for symptoms of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. (PGR2022-00054.) Biogen filed its Preliminary Response on November 8, 2022, and an institution decision is expected by February 8, 2023. Biogen has asserted the ’845 patent against Sandoz in the BPCIA litigation discussed above (1:22-cv-01190 D. Del.).

- Eylea® (aflibercept) / Zaltrap® (ziv-aflibercept): In 2021, Mylan filed IPRs against two method of treatment patents; these IPRs were resolved in 2022 (see below). In July and October 2022, Mylan filed an additional three IPRs challenging three different Regeneron patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 10,130,681 (the “’681 patent”), 10,888,601 (the “’601 patent”), and 10,857,205 (the “’205 patent”). (IPR2022-01225, -01226, and IPR2023-00099.) The PTAB granted institution on the ’681 and ’601 patents in January 2023. An institution decision on the ’205 patent is expected in April 2023. Separately, Apotex is challenging one additional patent, U.S. Patent No. 11,253,572 (the “’572 patent”). (IPR2022-01524.) An institution decision on the ’572 patent is expected in March 2023. All four Regeneron patents in these pending IPRs are asserted against Mylan in the BPCIA litigation discussed above (1:22-cv-00061 N.D. W. Va.)

Several disputes also reached resolution this year. For example:

- Eylea® (aflibercept) / Zaltrap® (ziv-aflibercept): In May 2021, Mylan filed two IPRs against two Regeneron method of treatment patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 9,669,069 and 9,254,338. (IPR2021-00880, -00881.) Both patents were subsequently asserted against Mylan in the BPCIA litigation discussed above (1:22-cv-00061 N.D. W. Va.). The PTAB granted institution of both IPRs in November 2021. Subsequently, in December 2021, Celltrion and Apotex filed petitions substantially similar to Mylan’s petitions and joined the instituted IPRs. (IPR2022-00257, -00258, -00298, -00301.) On November 9, 2022, the PTAB issued final written decisions finding both patents invalid. Regeneron has appealed both decisions to the Federal Circuit. Celltrion had also previously filed a PGR against U.S. Patent No. 10,857,231 (not asserted against Mylan in the BPCIA litigation) (PGR2021-00117), but the proceeding terminated when Regeneron disclaimed the challenged claims.

- anti-IL23p19 antibody: In May 2022, Sandoz filed a PGR against a formulation patent, U.S. Patent No. 11,078,265, owned by Boehringer Ingelheim and directed to a formulation of anti-IL-23p19 antibody. (PGR2022-00037.) The PTAB denied institution of PGR, finding that the patent was not eligible for post-grant review because petitioner had not shown that the patent was not entitled to its earliest priority date, which was before the March 16, 2013 cutoff date for PGRs. Sandoz filed a request for rehearing on December 7, 2022.

In addition, the Federal Circuit decided an appeal from a PTAB decision in 2022.

- Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim): In April 2022, the Federal Circuit issued a non-precedential decision related to a biologic patent owned by Amgen. See Amgen Inc. v. Vidal, No. 2019-2171, 2022 WL 1112817 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 14, 2022). The court reversed the PTAB’s determination in IPR2016-01542 that claims in Amgen’s U.S. Patent No. 8,952,138 (the “’138 patent”) were obvious. at *1. The ’138 patent relates to methods of refolding proteins by using a refolding buffer with specific characteristics. Id. Amgen had asserted the ’138 patent against Apotex in BPCIA litigation regarding Apotex’s filgrastim and pegfilgrastim biosimilars in 2015 (0:15-cv-61631 S.D. Fla.) That litigation was dismissed after a bench trial finding that Amgen failed to prove Apotex’s proposed product would infringe the ’138 patent claims. The Federal Circuit previously affirmed that finding in 2017. See Amgen Inc. v. Apotex Inc., 712 F. App’x 985 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The IPR persisted, with the Federal Circuit vacating the PTAB’s final written decision finding all claims unpatentable as obvious and remanding in view of Arthrex. See Amgen Inc. v. Iancu, No. 2019-2171, 2020 WL 10224674 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 24, 2020). After the second final written decision, Amgen appealed again, and this time secured a reversal based on an erroneous claim construction. Amgen Inc. v. Vidal, No. 2019-2171, 2022 WL 1112817 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 14, 2022). In light of the Federal Circuit’s affirmance of the District Court finding of non-infringement, Apotex did not participate in the appeals.

V. Biosimilar Regulatory Updates

In 2022, regulatory agencies continued to focus on biosimilars. Among other efforts, FDA announced several initiatives to facilitate biosimilar development. Regulatory agencies also addressed biologic drug pricing and anti-competitive behavior in the biosimilars space.

A. DHHS Report on Increasing Access to and Use of Biosimilars in Medicare Part D

In March 2022, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General issued a report titled “Medicare Part D and Beneficiaries Could Realize Significant Spending Reductions with Increased Biosimilar Use.” (OEI-05-20-00480.) The OIG analyzed biosimilar utilization and spending in Part D from 2015 to 2019 and calculated “multiple estimates to explore how Part D and beneficiary spending in CY 2019 could have changed had there been increased biosimilar use.” The OIG found that, since biosimilars were introduced in 2015, use and spending on biosimilars has increased every year, but most biosimilars were still used “far less frequently” than their reference products. The OIG recommended that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services “encourage plans to increase access to and use of biosimilars in Part D” and “monitor biosimilar coverage on formularies to identify concerning trends.” The report noted that “CMS concurred with [the] first recommendation and neither concurred nor nonconcurred with [the] second recommendation.”

B. FDA Efforts to Facilitate Biosimilar Development

On March 3, 2022, FDA posted a funding opportunity, Biosimilar User Fee Act (BsUFA) Research Grant (U01), “to support research projects that enhance biosimilar and interchangeable biological product development and regulatory science.” Project types included “analytical methodology (including bioassay) development, in silico tools, real world evidence, pharmacology studies, and ancillary studies in parallel to planned or ongoing clinical trials, and combinations of these project types.” FDA intended to commit up to $5 million in the 2022 fiscal year in support of the program. Applications closed on May 9, 2022.

On September 19, 2022, FDA hosted a virtual public workshop, “Increasing the Efficiency of Biosimilar Development Programs,” which focused on “comparative clinical studies associated with biosimilar development programs” and discussed “possible innovative ideas that have the potential to streamline and improve the efficiency of biosimilar development.” Materials from the workshop, including slides and recordings, are available on FDA’s website.

On October 3, 2022, FDA published its BsUFA reauthorization commitment letter for fiscal years 2023 to 2027 (BsUFA III). According to that letter, FDA will “pilot a regulatory science program focused on enhancing regulatory decision-making and facilitating science-based recommendations in areas foundational to biosimilar and interchangeable biological development.” The pilot program will focus on two demonstration projects: (1) advancing the development of interchangeable products, and (2) improving the efficiency of biosimilar product development.

On October 7, 2022, FDA announced the BsUFA rates for the 2023 fiscal year. (87 Fed. Reg. 61033.) The announcement includes forecasted workload volumes for the 2023 fiscal year. FDA estimates it will receive eight applications for biosimilar products requiring clinical data for approval and zero applications that do not require clinical data; it will invoice 72 BPD program fees; and it will collect fees for approximately 23.5 new BPD programs, no reactivations, and approximately 97.75 annual BPD programs.

C. Regulatory Efforts to Address Anti-Competitive Behavior and Drug Pricing

In 2022, USPTO and FDA worked towards addressing the issues raised in President Biden’s July 9, 2021 Executive Order 14036 on “Promoting Competition in the American Economy.” Below, we focus on the regulatory activities that most directly impact the biosimilars field.

As discussed in Fish & Richardson’s Biosimilars 2021 Year in Review, Executive Order 14036 directed FDA to: (1) “improv[e] and clarify[] the standards for interchangeability of biological products”; (2) “support[] biosimilar product adoption by providing effective educational materials and communications to improve understanding of biosimilar and interchangeable products among healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers”; (3) facilitate the “development and approval of biosimilar and interchangeable products”; and (4) work with FTC to identify and address “efforts to impede generic drug and biosimilar competition.” “[T]o help ensure that the patent system, while incentivizing innovation, does not also unjustifiably delay generic drug and biosimilar competition beyond that reasonably contemplated by applicable law,” the Executive Order also directed FDA to write a letter to the Director of USPTO “enumerating and describing any relevant concerns of the FDA.”

On September 10, 2021, Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock sent a letter to Acting Director of USPTO Andrew Hirshfeld pursuant to Executive Order 14036 “in the hope of further developing” FDA’s engagement with USPTO “with the goal of increasing competition and access to affordable drugs while respecting the need to preserve patent rights and incentives for innovation generally.” Dr. Woodcock offered several suggestions for USPTO’s consideration.

On July 6, 2022, USPTO Director Vidal responded to FDA’s letter. Director Vidal noted that she “share[s] the Administration’s mission with regard to drug accessibility” and attached “USPTO’s current thoughts on what we can do as an agency, and in collaboration with the FDA, to make real progress.” According to that attachment, USPTO is prioritizing “enhance[d] collaboration with other agencies on key technology areas, including pharmaceuticals and biologics;” improving procedures for obtaining a patent so that USPTO issues “robust and reliable patents”; improving the process for challenging issued patents before the PTAB (e.g., IPRs); improving public participation; and considering and evaluating “new proposals for incentivizing and protecting the investment essential for bringing life-saving and life-altering drugs to market while minimizing any unnecessary delay getting generic, biosimilar, and more affordable versions of those drugs into the hands of Americans who need them.”

To promote “robust and reliable patents,” USPTO has also taken steps to align statements made by companies and their representatives before USPTO and FDA. On July 29, 2022, USPTO issued a notice titled “Duties of Disclosure and Reasonable Inquiry During Examination, Reexamination, and Reissue, and for Proceedings Before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.” (87 Fed. Reg. 45764.) The notice “is intended to clarify the duties, including as to materials or statements material to patentability or statements made to the USPTO that are inconsistent with statements submitted to the FDA and other governmental agencies” and is part of USPTO’s efforts to put into effect Executive Order 14036. The notice also addresses concerns expressed by Senators Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Thom Tillis (R-NC) in a September 9, 2021 letter about patent applicants “making inappropriate conflicting statements in submissions to the [USPTO] and other federal agencies.” The USPTO notice clarified, inter alia, that “each party presenting a paper to the USPTO, whether a practitioner or non-practitioner, has a duty to perform an inquiry that is reasonable under the circumstances” to identify and disclose materials that are “material to … patentability” submitted to or received from other government agencies. (For more information, see “What to Know About the USPTO’s Duty of Candor Guidance Regarding FDA Submissions.”)

On October 4, 2022, USPTO published a Request for Comments on USPTO Initiatives To Ensure the Robustness and Reliability of Patent Rights, which seeks comments on the initiatives described in Director Vidal’s July 6, 2022 letter to FDA as well as questions concerning “patent thickets” raised by a group of Senators in a June 8, 2022 letter to USPTO. The comment period closed on January 3, 2023. Relatedly, on November 4, 2022, USPTO hosted a webinar on the Request for Comments on Initiatives to Ensure the Robustness and Reliability of Patent Rights.

On November 7, 2022, USPTO also published a Notice of Public Listening Session and Request for Comments on Joint USPTO-FDA Collaboration Initiatives. (87 Fed. Reg. 67019.) The listening session is scheduled for January 19, 2023, and the comment period is scheduled to close on February 6, 2023. Topics for comment include:

- Publicly available FDA resources for USPTO patent examiner training;

- Mechanisms to assist patent examiners in identifying inconsistent statements submitted to USPTO and FDA;

- How America Invents Act proceedings (e.g., IPRs) may intersect with Hatch-Waxman paragraph IV disputes and the BPCIA patent dance framework;

- How USPTO and FDA can further collaborate with respect to patent term extension determinations;

- Policy considerations or concerns regarding method of use patents and associated FDA use codes, including with respect to “skinny labeling”;

- Policy considerations or concerns regarding the patenting of risk evaluation and mitigation strategies associated with certain FDA-approved products;

- Steps USPTO and FDA could take collaboratively to address “concerns about the potential misuse of patents to improperly delay competition or to promote greater availability of generic versions of scarce drugs that are no longer covered by patents”; and

- Any other related suggestions for USPTO-FDA collaboration.

On December 5, 2022, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Representative Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) wrote a letter to USPTO about Director Vidal’s July 6, 2022 letter and USPTO’s ongoing collaborations with FDA. The legislators expressed “ongoing concerns with the high cost of prescription drugs in America and the persistence of anti-competitive abuses of our patent system” and “concern[] that USPTO is not moving quickly or aggressively enough to combat abuses of the patent system.” They requested that USPTO answer several inquiries by December 19, 2022, including, inter alia, an update on collaborative efforts between FDA and USPTO, information about a process USPTO has put in place for the PTAB to share feedback relating to ex parte appeals, data relating to obviousness-type double patenting rejections and compliance rates with the requirement to file terminal disclaimers, information about enforcement of the duty of disclosure, and information about USPTO’s funding structure. As of early January 2023, we have not been able to locate a response from USPTO.

Back to top ↑VI. Legislation Affecting Biosimilars

A. Federal Legislation

Enacted Legislation

President Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 on August 16, 2022. On October 3, 2022, the provisions related to price-setting for biosimilars in Medicare under Section 11403 went into effect. Under Section 11403, Medicare Part B will pay Average Sales Price plus 8%, instead of ASP plus 6%, for biosimilars whose ASP does not exceed the price of the associated reference biological product.

On September 30, 2022, President Biden signed into law the FDA User Fee Reauthorization Act of 2022, which includes the second reauthorization of the Biosimilar User Fee Act (BsUFA III) that enables FDA to assess and collect fees for biosimilars during fiscal years 2023–2027. The original BsUFA was enacted in 2012, and it was reauthorized in 2017. The latest iteration of BsUFA was developed through collaboration between FDA and industry representatives. According to FDA, the funding received under the law is dedicated “to expediting the review process for biosimilar biological products” and “facilitates the development of safe and effective biosimilar products for the American public.”

Proposed Legislation

With more FDA-approved interchangeable biosimilars in the pipeline, federal lawmakers have begun introducing new legislation aimed at improving patient access to cost-saving biosimilars by removing barriers to substitution and increasing public trust in interchangeable biosimilars. While this legislation was not enacted by the 117th Congress, it provides insight into those issues that may be the focus of future legislation.

For example, on May 25, 2022, Senators Tim Kaine (D-VA), Susan Collins (R-ME), and Maggie Hassan (D-NH) introduced the Interchangeable Biologics Clarity Act (S. 4303). The stated purpose of the bill is to “provide for a period of exclusivity for first interchangeable biological products.” The proposed law would amend Section 351(k)(6) of the Public Health Service Act with the goal of providing FDA with additional clarity around exclusivity periods for interchangeable biological products and allowing products that can be easily substituted to treat the same condition to enter the market faster.

On September 19, 2022, Representatives Mariannette Miller-Meeks, M.D. (R-IA), Greg Murphy, M.D. (R-NC), Nanette Diaz Barragán (D-CA), and Ann Kuster (D-NH) introduced the Biologics Competition Act of 2022 (H.R. 8877). The bill seeks to direct the Secretary of Health and Human Services “to evaluate the extent to which the substitution of interchangeable biological products may be impeded by differences between the system for determining a biological product to be interchangeable and the system for assigning therapeutic equivalence ratings to drugs, and for other purposes.”

On November 17, 2022, Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) introduced the Biosimilar Red Tape Elimination Act (S. 6), which seeks to reduce consumer costs and increase competition within the biological drug market by streamlining FDA’s biosimilar approval process. In particular, the bill prohibits FDA from requiring biosimilars to undergo “switching studies” to receive an interchangeable designation.

There were also a number of other newly-introduced bills in 2022 that address biosimilars, for example the Biologics Market Transparency Act of 2022 (H.R. 7035), introduced on March 9, 2022, and the Reducing Animal Testing Act (S. 4288), introduced on May 19, 2022.

Back to top ↑VII. Conclusion

2022 was a remarkable year in many respects for the maturing U.S. biosimilars field, with new launches and approvals and new legal issues explored. 2023 is poised to bring even more developments.

Biosimilars stakeholders are closely watching the market for AbbVie’s Humira® (adalimumab), one of the top grossing biologic drug products. Ten or more adalimumab biosimilar companies have settled with AbbVie with permitted launch dates in 2023. Eight adalimumab biosimilars were FDA-approved by the end of 2022 and could potentially launch in 2023.

The biosimilar market could also expand with additional product approvals. For example, FDA recently accepted biosimilar BLAs for Actemra® (tocilizumab), a newer reference product first FDA-approved in 2010 for which there are currently no approved biosimilars. Other companies have renewed their commitment to biosimilars. Reuters has reported that Teva and Sandoz are both “planning a significant ramp-up in production of biosimilars,” with Teva reporting 13 biosimilars in development and Sandoz reporting 15 biosimilars in development.

This is all in addition to new expected guidance from the courts and regulatory agencies on how to navigate thorny issues related to regulatory approval and patent clearance.

Back to top ↑APPENDIX A:

|

Biosimilar |

Reference Product |

Biosimilar Code Name |

FDA Approval Date |

Time from BLA Acceptance to Approval4 |

Commercial Launch Date |

Reported Discount at Launch |

|

Idacio® (Fresenius Kabi) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-aacf |

December 13, 2022 |

12 months |

No earlier than 2023 per settlement |

|

|

Vegzelma® (Celltrion) |

Avastin® (Roche / Genentech) |

bevacizumab-adcd |

September 27, 2022 |

12 months |

||

|

Stimufend® (Fresenius Kabi) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-fpgk |

September 1, 2022 |

17 months |

||

|

Cimerli™ (Coherus / Bioeq) |

Lucentis® (Roche / Genentech) |

ranibizumab-eqrn |

August 2, 2022 (Interchangeable) |

12 months |

October 3, 2022 |

30% off WAC of Lucentis® |

|

Fylnetra® (Amneal / Kashiv) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-pbbk |

May 27, 2022 |

22 months (first submission Aug. 2020; resubmitted Nov. 2021) |

||

|

Alymsys® (Amneal / mAbxience) |

Avastin® (Roche / Genentech) |

bevacizumab-maly |

April 13, 2022 |

12 months |

October 3, 2022 |

|

|

Releuko® (Amneal / Kashiv) |

Neupogen® (Amgen) |

filgrastim-ayow |

February 25, 2022 |

43.5 months (first submission July 2017; resubmitted Aug. 2021) |

November 22, 2022 |

|

|

Yusimry™ / CHS-1420 (Coherus) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-aqvh |

December 17, 2021 |

12 months |

No earlier than 2023 per settlement |

|

|

Rezvoglar™ (Eli Lilly) |

Lantus® (Sanofi) |

insulin glargine-aglr |

December 17, 2021 Interchangeable: November 16, 2022 |

12 months |

||

|

Byooviz™ (Samsung Bioepis / Biogen) |

Lucentis® (Roche / Genentech) |

ranibizumab-nuna |

September 17, 2021 |

12 months |

June 2, 2022 |

40% off WAC of Lucentis® |

|

Semglee® (Mylan (Viatris) / Biocon) |

Lantus® (Sanofi) |

insulin glargine-yfgn |

July 28, 2021 (Interchangeable) |

31 months5 |

August 31, 2020 (Interchangeable: November 2021) |

Unbranded: 65% off WAC of Lantus® Branded Semglee®: 5% off WAC of Lantus®, with high rebates |

|

Riabni™ (Amgen) |

Rituxan® (Roche/ Genentech) |

rituximab-arrx |

December 17, 2020 |

12 months |

January 12, 2021 |

16.7% off ASP and 23.7% off WAC of Rituxan®; and 15.2% off WAC of Truxima® |

|

Hulio® (Mylan) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-fkjp |

July 6, 2020 |

12 months |

No earlier than 2023 per settlement |

|

|

Nyvepria™ (Pfizer) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-apgf |

June 10, 2020 |

12 months |

December 2020 |

37% off WAC of Neulasta® |

|

Avsola® (Amgen) |

Remicade® (Johnson & Johnson) |

infliximab-axxq |

December 6, 2019 |

12 months |

July 2020 |

57% off WAC of Remicade® |

|

Abrilada™ (Pfizer) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-afzb |

November 15, 2019 |

12 months |

No earlier than 2023 per settlement |

|

|

Ziextenzo® (Sandoz) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-bmez |

November 4, 2019 |

50 months (first submission Nov. 2015; resubmitted Feb. 2019) |

November 15, 2019 |

37% off WAC of Neulasta® |

|

Hadlima® (Samsung Bioepis) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-bwwd |

July 23, 2019 |

12 months |

No earlier than 2023 per settlement |

|

|

Ruxience® (Pfizer) |

Rituxan® (Roche / Genentech) |

rituximab-pvvr |

July 23, 2019 |

12 months |

January 23, 2020 |

24% off WAC of Rituxan® |

|

Kanjinti® (Amgen/ Allergan) |

Herceptin® (Roche / Genentech) |

trastuzumab-anns |

June 13, 2019 |

22.5 months (first submission July 2017; resubmitted Dec. 2018) |

July 18, 2019 |

13% off ASP and 15% off WAC of Herceptin® |

|

Zirabev® (Pfizer) |

Avastin® (Roche / Genentech) |

bevacizumab-bvzr |

June 27, 2019 |

12 months |

December 31, 2019 |

23% off WAC of Avastin® |

|

Eticovo™ (Samsung Bioepis) |

Enbrel® (Amgen) |

etanercept-ykro |

April 25, 2019 |

23 months (first submission May 2017; resubmitted Oct. 2018) |

||

|

Trazimera® (Pfizer) |

Herceptin® (Roche / Genentech) |

trastuzumab-qyyp |

March 11, 2019 |

20.5 months (first submission June 22, 2017; resubmitted Sept. 28, 2018) |

February 15, 2020 |

22% off WAC of Herceptin® |

|

Ontruzant® (Samsung Bioepis/ Merck) |

Herceptin® (Roche / Genentech) |

trastuzumab-dttb |

January 18, 2019 |

15 months |

April 15, 2020 |

15% off Herceptin® |

|

Herzuma® (Celltrion / Teva) |

Herceptin® (Roche / Genentech) |

trastuzumab-pkrb |

December 14, 2018 |

18.5 months (first submission May 2017; resubmitted June 2018) |

March 16, 2020 |

10% off WAC of Herceptin® |

|

Truxima® (Celltrion / Teva) |

Rituxan® (Roche / Genentech) |

rituximab-abbs |

November 28, 2018 |

19 months (first submission April 2017; resubmitted May 2018) |

November 11, 2019 |

10% off WAC of Rituxan® |

|

Udenyca® (Coherus) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-cbqv |

November 2, 2018 |

27 months (first submission Aug. 2016; resubmitted May 2018) |

January 3, 2019 |

33% off WAC of Neulasta® |

|

Hyrimoz® (Sandoz) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-adaz |

October 30, 2018 |

12 months |

No earlier than 2023 per settlement |

|

|

Nivestym® (Pfizer / Hospira) |

Neupogen® (Amgen) |

filgrastim-aafi |

July 20, 2018 |

10 months |

October 1, 2018 |

30.3% off WAC of Neupogen®; 20.3% off WAC of Zarxio®; and 14.1% off WAC of Granix® |

|

Fulphila® (Mylan / Biocon) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-jmdb |

June 4, 2018 |

18 months (first submission Feb. 2017; resubmitted Dec. 2017) |

July 26, 2018 |

33% off WAC of Neulasta® |

|

Retacrit® (Pfizer/ Hospira) |

Epogen®/ Procrit® (Amgen/ J&J) |

epoetin alfa-epbx |

May 15, 2018 |

41 months (first submission Jan. 2015; resubmitted Dec. 2016) |

November 12, 2018 |

33.5% off WAC of Epogen®; 57.1% off WAC of Procrit® |

|

Ixifi® (Pfizer) |

Remicade® (Johnson & Johnson) |

infliximab-qbtx |

December 13, 2017 |

10 months |

No U.S. launch intended |

|

|

Ogivri® (Mylan) |

Herceptin® (Roche / Genentech) |

trastuzumab-dkst |

December 1, 2017 |

13 months |

December 2, 2019 |

15% off WAC of Herceptin® |

|

Mvasi® (Amgen / Allergan) |

Avastin® (Roche / Genentech) |

bevacizumab-awwb |

September 14, 2017 |

10 months |

July 18, 2019 |

12% off ASP and 15% off WAC of Avastin® |