Blog

Biosimilars 2020 Year in Review

Fish & Richardson

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

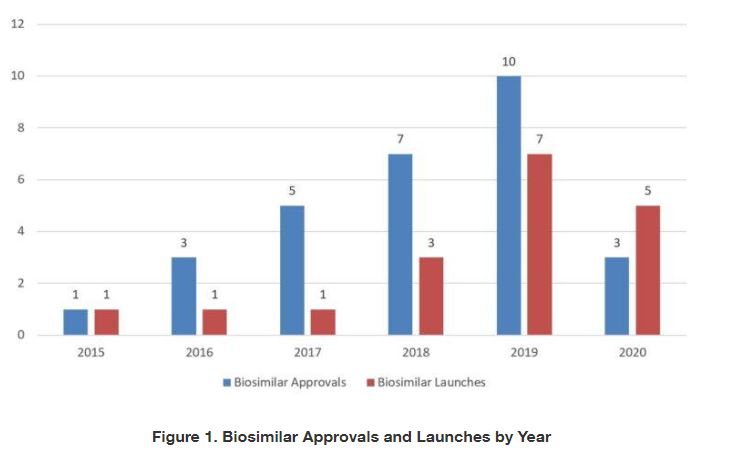

The biosimilar pathway was designed to increase competition for biologics and reduce healthcare costs. Yet 2020 saw a slowdown in biosimilar activity with the lowest number of annual biosimilar approvals since 2016 and fewer product launches than 2019—as well as a decrease in district court litigation and post-grant proceedings. At the same time, market uptake of biosimilars in the United States continued to increase, suggesting that there is room for expansion of biosimilars in the U.S. market.

2020 also marked the ten-year anniversary of the enactment of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), which created the abbreviated licensure pathway for biosimilar products to attain FDA approval. With this milestone on March 23, 2020, insulin and other biological products previously regulated as “drugs” transitioned to regulation as biologics, paving the way for increased biosimilar diversity.

Below, we review these notable developments and more from 2020.

I. Biosimilar Approvals and Launches in 2020

II. Biosimilar Regulatory Updates

III. Legislation Relating to Biologics and Biosimilars

IV. BPCIA Litigation

V. Antitrust Litigation

VI. Post-Grant Challenges at the PTAB

VII. Conclusion

I. Biosimilar Approvals and Launches in 2020

For the first time since FDA licensed the first biosimilar, Sandoz’s Zarxio® (filgrastim-sndz), in 2015, the United States saw a decrease in annual biosimilar approvals in 2020. In 2019, FDA approved a record-breaking ten biosimilars. But in 2020, FDA only approved three new biosimilars: Mylan’s Hulio®, a Humira® (adalimumab) biosimilar; Pfizer’s Nyvepria™, a Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim) biosimilar; and Amgen’s Riabni™, a Rituxan® (rituximab) biosimilar. None of these was the first biosimilar for its respective reference product.

In addition, fewer new biosimilars entered the market this past year, with five biosimilar launches in 2020 as compared to seven in 2019. The newly launched biosimilars in 2020 included:

- one Rituxan® (rituximab) biosimilar, Pfizer’s Ruxience®;

- one Remicade® (infliximab) biosimilar, Amgen’s Avsola™; and

- three Herceptin® (trastuzumab) biosimilars, Celltrion’s Herzuma®, Samsung Bioepis’ Ontruzant®, and Pfizer’s Trazimera™.

The following tables summarize publicly available information regarding approved and select pending biosimilar Biologics License Applications (BLAs), and illustrate additional trends in the biosimilars industry.

Table 1 summarizes information related to the biosimilars approved as of 2020. FDA has approved 29 biosimilars corresponding to nine different reference products. While the total number of biosimilars approved by FDA in 2020 decreased relative to the last few years, the review periods for those biosimilars—usually 12 months from the time FDA accepts the BLA to approval—do not appear to have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the 29 approved biosimilars, 18 had been launched in the United States by the end of 2020.

Table 1. Biosimilars Approved as of 2020

| Biosimilar Drug | Reference Product | Biosimilar Code Name | FDA Approval Date | Time from BLA Acceptance to Approval | Commercial Launch Date | Reported Discount at Launch |

| Riabni™ (Amgen) |

Rituxan® (Roche/Genentech) |

rituximab-arrx | December 17, 2020 | 12 months | January 2021 | 16.7% off ASP and 23.7% off WAC of Rituxan®; and 15.2% off WAC of Truxima® |

| Hulio® (Mylan) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-fkjp | July 6, 2020 | 12 months | No earlier than July 31, 2023 per settlement | |

| Nyvepria™ (Pfizer) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-apgf | June 10, 2020 | 12 months | ||

| Avsola™ (Amgen) |

Remicade® (Johnson & Johnson) |

infliximab-axxq | December 6, 2019 | 12 months | July 2020 | 57% off WAC of Remicade® |

| Abrilada™ (Pfizer) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-afzb | November 15, 2019 | 12 months | No earlier than November 20, 2023 per settlement | |

| Ziextenzo™ (Sandoz) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-bmez | November 4, 2019 | 50 months (first submission Nov. 2015; resubmitted Feb. 2019) |

November 15, 2019 | 37% off WAC of Neulasta® |

| Hadlima™ (Samsung Bioepis) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-bwwd | July 23, 2019 | 12 months | No earlier than June 30, 2023 per settlement | |

| Ruxience™ (Pfizer) |

Rituxan® (Roche/Genentech) |

rituximab-pvvr | July 23, 2019 | 12 months | January 23, 2020 | 24% off WAC of Rituxan® |

| Kanjinti™ (Amgen/Allergan |

Herceptin® (Roche/Genentech) |

trastuzumab-anns | June 13, 2019 | 22.5 months (first submission July 2017; resubmitted Dec. 2018) |

July 18, 2019 | 13% off ASP and 15% off WAC of Herceptin® |

| Zirabev™ (Pfizer) |

Avastin® (Roche) |

bevacizumab-bvzr | June 27, 2019 | 12 months | December 31, 2019 | 23% off WAC of Avastin® |

| Eticovo™ (Samsung Bioepis) |

Enbrel® (Amgen) |

etanercept-ykro | April 25, 2019 | 23 months (first submission May 2017; resubmitted Oct. 2018) |

||

| Trazimera™ (Pfizer) |

Herceptin® (Roche/Genentech) |

trastuzumab-qyyp | March 11, 2019 | 20.5 months (first submission June 22, 2017; resubmitted Sept. 28, 2018) |

February 15, 2020 | 22% off WAC of Herceptin® |

| Ontruzant® (Samsung Bioepis/Merck) |

Herceptin® (Roche/Genentech) |

trastuzumab-dttb | January 18, 2019 | 15 months | April 15, 2020 | 15% off Herceptin® |

| Herzuma® (Celltrion/Teva) |

Herceptin® (Roche/Genentech) |

trastuzumab-pkrb | December 14, 2018 | 18.5 months (first submission May 2017; resubmitted June 2018) |

March 16, 2020 | 10% off WAC of Herceptin® |

| Truxima® (Celltrion/Teva) |

Rituxan® (Roche/Genentech) |

rituximab-abbs | November 28, 2018 | 19 months (first submission April 2017; resubmitted May 2018) |

November 11, 2019 | 10% off WAC of Rituxan® |

| Udenyca® (Coherus) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-cbqv | November 2, 2018 | 27 months (first submission Aug. 2016; resubmitted May 2018) |

January 3, 2019 | 33% off WAC of Neulasta® |

| Hyrimoz™ (Sandoz) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-adaz | October 30, 2018 | 12 months | No earlier than September 30, 2023 per settlement | |

| Nivestym™ (Pfizer/Hospira) |

Neupogen® (Amgen) |

filgrastim-aafi | July 20, 2018 | 10 months | October 1, 2018 | 30.3% off WAC of Neupogen®; 20.3% off WAC of Zarxio®; and 14.1% off WAC of Granix® |

| Fulphila™ (Mylan/Biocon) |

Neulasta® (Amgen) |

pegfilgrastim-jmdb | June 4, 2018 | 18 months (first submission Feb. 2017; resubmitted Dec. 2017) |

July 26, 2018 | 33% off WAC of Neulasta® |

| Retacrit® (Pfizer/Hospira) |

Epogen®/Procrit® (Amgen/Johnson & Johnson) |

epoetin alfa-epbx | May 15, 2018 | 41 months (first submission Jan. 2015; resubmitted Dec. 2016) |

November 12, 2018 | 33.5% off WAC of Epogen®; 57.1% off WAC of Procrit® |

| Ixifi® (Pfizer) |

Remicade® (Johnson & Johnson) |

infliximab-qbtx | December 13, 2017 | 10 months | No U.S. launch intended | |

| Ogivri® (Mylan) |

Herceptin® (Roche/Genentech) |

trastuzumab-dkst | December 1, 2017 | 13 months | December 2, 2019 | 15% off WAC of Herceptin® |

| Mvasi™ (Amgen/Allergan) |

Avastin® (Roche/Genentech) |

bevacizumab-awwb | September 14, 2017 | 10 months | July 18, 2019 | 12% off ASP and 15% off WAC of Avastin® |

| Cyltezo® (Boehringer Ingelheim) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-adbm | August 25, 2017 | 10 months | No earlier than July 1, 2023 per settlement | |

| Renflexis® (Samsung Bioepis/Merck) |

Remicade® (Johnson & Johnson) |

infliximab-abda | April 21, 2017 | 13 months | July 2017 | 35% off WAC of Remicade® |

| Amjevita™ (Amgen) |

Humira® (AbbVie) |

adalimumab-atto | September 23, 2016 | 10 months | No earlier than January 31, 2023 per settlement | |

| Erelzi® (Sandoz) |

Enbrel® (Amgen) |

etanercept-szzs | August 30, 2016 | 13 months | ||

| Inflectra® (Pfizer/Celltrion) |

Remicade® (Johnson & Johnson) |

infliximab-dyyb | April 5, 2016 | 20 months (first submission Aug. 2014; resubmitted Oct. 2015) |

November 2016 | 15% off WAC of Remicade® |

| Zarxio® (Sandoz) |

Neupogen® (Amgen) |

filgrastim-sndz | March 6, 2015 | 10 months | September 2015 | 15% off WAC of Neupogen® |

Despite the low number of approvals in 2020, FDA has reported numerous biosimilars-related submissions in the < for Fiscal Year (FY) 2020,[2] including seven original biosimilar BLA submissions in FY 2020. As of FY 2020 Q4, there were 84 biosimilar development programs enrolled in the biosimilar biological product development (BPD) program. Table 2 below identifies selected pending biosimilar BLAs for which information is publicly available.

Table 2. Select Pending Biosimilar BLAs as of December 2020

| Proposed Biosimilar | Reference Product | Nonproprietary Name | FDA Status |

| AVT02 (Alvotech) | Humira® (AbbVie) | adalimumab | BLA Accepted: November 2020 |

| SB11 (Samsung Bioepis/Biogen) | Lucentis® (Roche/Genentech) | ranibizumab | BLA Accepted: November 2020 |

| MYL-14020 (Mylan/Biocon) | Avastin® (Roche/Genentech) | bevacizumab | BLA Accepted: March 2020 FDA Goal Date: December 27, 2020, but delayed due to COVID-19 pandemic |

| SB8 (Samsung Bioepis) | Avastin® (Roche) | bevacizumab | BLA Submitted: September 2019 BLA Accepted: November 2019 |

| MSB11455 (Fresenius Kabi) | Neulasta® (Amgen) | pegfilgrastim | BLA Accepted: May 2020 |

| FYB201 (Coherus/Bioeq) | Lucentis® (Roche) | ranibizumab | BLA Submitted: December 2019 BLA Withdrawn: February 2020 |

In addition, FDA may be on the cusp of approving its first insulin biosimilar. On August 31, 2020, Biocon Biologics and Mylan announced the launch of Semglee™ (insulin glargine injection), which was approved as an equivalent to Sanofi’s Lantus® in June 2020 via a New Drug Application (NDA) filed under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act. As of March 23, 2020, Mylan’s NDA for Semglee™ was “deemed” to be a BLA, and Mylan has announced its submission of “all necessary documentation” to FDA for approval of Semglee™ as a biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar product.

Market uptake of biosimilars has generally trended upwards in 2020. Several sources[3] have reported current market uptake for biosimilars of supportive care biologics (Neulasta®, Neupogen®, and Epogen®) on the order of 25-50% of market share. Biosimilars of oncology therapeutics (Herceptin®, Avastin®, and Rituxan®) have taken 20-40% of their respective markets. These include three biosimilars launched in the second half of 2019—Mvasi™ (bevacizumab), Kanjinti™ (trastuzumab), and Truxima® (rituximab)—that have quickly made inroads into the reference product market.

Yet biosimilars of anti-TNFα antibodies (including Remicade®, Humira®, and Enbrel®) continue to struggle to enter the market and gain a significant foothold.[4] As of December 2020, only Remicade® faced biosimilar competition—and, despite the fact that Remicade® biosimilars have been available since 2016, they have captured only 20% of the market. No Humira® or Enbrel® biosimilars have launched. All currently approved Humira® biosimilars cannot launch until 2023 per settlements with AbbVie. Manufacturers of Enbrel® biosimilars (Sandoz and Samsung Bioepis) have been embroiled in patent litigation with Immunex, and, as discussed below, Sandoz recently lost its appeal to the Federal Circuit.

Table 3 provides a summary of the biosimilars market, as derived from a 2020 Amgen market report.[5]

| Category | Reference Product | Number of Approved Biosimilars | Number of Launched Biosimilars | Earliest Biosimilar Launch Date | Biosimilar Share by Volume |

| Oncology Therapeutics | Herceptin® (trastuzumab) |

5 | 5 | July 18, 2019 | 40% |

| Oncology Therapeutics | Avastin® (bevacizumab) |

2 | 2 | July 18, 2019 | 40% |

| Oncology Therapeutics | Rituxan® (rituximab) |

3 | 2 | November 11, 2019 | 20% |

| Supportive Care | Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim) |

4 | 3 | July 26, 2018 | 28% |

| Supportive Care | Neupogen® (filgrastim) |

2 | 2 | September 2015 | 52% |

| Supportive Care | Epogen®/Procrit® (epoetin alfa) |

1 | 1 | November 12, 2018 | 25% |

| Inflammation | Remicade® (infliximab) |

4 | 3 | November 2016 | 20% |

| Inflammation | Humira® (adalimumab) |

6 | 0 | Not yet launched | 0% |

| Inflammation | Enbrel® (etanercept) |

2 | 0 | Not yet launched | 0% |

II. Biosimilar Regulatory Updates

In 2020, FDA continued to focus on biosimilars through guidance documents, citizen petitions, and other mechanisms.

A. FDA Addresses Biosimilar Competition

In February 2020, FDA and FTC took steps to encourage biosimilar competition, with a focus on truthful and non-misleading advertising. On February 3, 2020, FDA and FTC issued a Joint Statement of the Food & Drug Administration and the Federal Trade Commission Regarding a Collaboration to Advance Competition in the Biologic Marketplace. The statement advanced four stated goals: (1) to promote greater competition in biologics markets, (2) to deter behavior that impedes access to samples needed for biologic development, (3) to take appropriate action against false or misleading communications about biologics, and (4) to review patent settlement agreements involving biologics for antitrust violations.

Coinciding with this announcement, FDA issued draft guidance titled “Promotional Labeling and Advertising Considerations for Prescription Biological Reference and Biosimilar Products Questions and Answers.” The guidance explains that determining whether promotional material is truthful and non-misleading involves a “fact-specific” analysis based on a number of factors, including “how the information is presented,” “the type and quality of the data relied on,” and “contextual and disclosure considerations.” The guidance further states that promotional material may be false or misleading if it creates an impression that there are clinically meaningful differences between the reference product and the biosimilar in terms of safety, purity, or potency, such as representations that a reference product is safer or more effective than its biosimilar product, or suggestions that a biosimilar is not highly similar to its reference product.

Around the same time, FDA also responded to Pfizer’s citizen petition, originally filed in August 2018. In its petition, Pfizer urged FDA to issue guidance “to ensure truthful and non-misleading communications by sponsors concerning the safety and effectiveness of biosimilars, including interchangeable biologics, relative to reference product(s).” FDA granted Pfizer’s citizen petition in part to the extent that Pfizer requested draft guidance regarding promotional labeling and advertising considerations for biologics and biosimilars, but denied Pfizer’s request to include specific content in the guidance, which was to be determined by FDA after consideration of public comments on the guidance.

In December 2020, Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) filed a citizen petition asking FDA to change its interpretation of the term “strength” as used in the BPCIA for parenteral solutions to mean “total drug content” without regard to concentration. According to BI’s petition, a change in interpretation is necessary to: (1) “ensure [FDA’s] interpretation is consistent with the clear meaning of the [BPCIA]; (2) prevent abusive ‘evergreening’ tactics from stifling competition of affordable biosimilar and interchangeable biological products; and (3) maintain fair and consistent treatment of all similarly situated parenteral biological products.” BI argues that FDA’s current interpretation “encourages, or at least permits, brand sponsors to use minor concentration changes as an anti-competitive tactic.” BI points to Humira® (adalimumab) as an example. BI and other biosimilar manufacturers have approved Humira® biosimilars with 50 mg/mL concentrations, but as of July 2018 Humira® is now also marketed at a 100 mg/mL concentration—and no currently approved adalimumab biosimilars can be considered biosimilar or interchangeable to this higher concentration under FDA’s current approach. FDA has acknowledged receipt of BI’s petition, but has not yet provided any substantive feedback.

B. FDA Provides Additional Guidance on Biosimilarity and Interchangeability

In February 2020, FDA issued draft guidance titled “Biosimilars and Interchangeable Biosimilars: Licensure for Fewer Than All Conditions of Use for Which the Reference Product Has Been Licensed.” In this draft guidance, FDA confirms that “[a] biosimilar or interchangeable biosimilar may be licensed only for conditions of use that have been previously licensed for the reference product.” But FDA acknowledges that, a “variety of circumstances,” such as orphan-drug exclusivities and patent protections, may cause applicants to seek licensure for fewer indications. The draft guidance provides suggestions on how to plan for approval of fewer than all indications.

In November 2020, FDA released new draft guidance for industry titled “Biosimilarity and Interchangeability: Additional Draft Q&As on Biosimilar Development and the BPCI Act.” The new draft guidance describes FDA’s current thinking on, inter alia, seeking FDA review of biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar BLAs and labeling of interchangeables. The draft guidance states, for example, that FDA intends to review new BLAs submitted under Section 351(k) as biosimilars (as well as interchangeables if indicated), unless the cover letter clearly states that the applicant is only seeking licensure as an interchangeable. The guidance also provides exemplary language for indicating interchangeability on a label and clarifies that many of the guidelines for biosimilar labels also apply to interchangeable labels. For example, the draft guidance states that clinical studies supporting interchangeability (like clinical studies supporting biosimilarity) should not be included on the label.

C. Transition of Insulin and Other Biological Products Previously Regulated as “Drugs” to Biologics Regulation

On March 23, 2020, the “deemed to be a license” provision of the BPCIA went into effect, changing the way insulin and certain other biological products are reviewed and approved. Typically, “drugs” and “biologics” are subject to different laws and regulations. While drugs are regulated under the FD&C Act as New Drug Applications (NDAs), biologics are regulated under the PHS Act. Historically, a subset of biologics, including insulin and human growth hormones, were approved as drugs under the FD&C Act and not as biologics under the PHS Act. As a result, applicants could not seek approval of biosimilars or interchangeables of these products under the BPCIA. As of the March 23, 2020 transition, however, all “biological product” applications previously approved under the FD&C Act were “deemed” approved under the PHS Act, and companies can now seek biosimilars and interchangeables of these biological products.

FDA was involved in preparing for the transition date by issuing relevant guidance and promulgating a final rule addressing the definition of “biological products” subject to the transition. Under that rule, FDA aligned the regulatory definition of “biological product” with the definition under the statute, which provides that a “biological product” includes a “protein.” For example, FDA interpreted the term “protein” to mean “any amino acid polymer with a specified defined sequence that is greater than 40 amino acids in size.”

As noted above, companies are already taking advantage of these new designations. In particular, Mylan has announced its submission of “all necessary documentation” to FDA for approval of Semglee™, an insulin product, as an interchangeable biosimilar biological product.

D. FDA Updates the Purple Book

Over the past year, FDA has transitioned the so-called “Purple Book” to a searchable, public-facing online database. The new searchable database is available at https://purplebooksearch.fda.gov/, and now contains information on “all FDA-licensed (approved) biological products regulated by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), including licensed biosimilar and interchangeable products, and their reference products” and “all FDA-licensed allergenic, cellular and gene therapy, hematologic, and vaccine products regulated by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER).” The Purple Book currently includes information on, e.g., the date of approval, the type of BLA approved, and whether there are approved biosimilars or interchangeables. The Purple Book does not currently include any patent information, but that will change in the future per recent legislation, as discussed below.

E. FDA Addresses the COVID-19 Global Pandemic

As a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic, FDA has taken several measures, including delaying inspections. This has held up at least one anticipated new biosimilar, Biocon and Mylan’s Avastin® biosimilar MYL-14020. It has been reported that a final decision on their biosimilar—expected towards the end of 2020—was delayed because FDA was unable to conduct an inspection of the manufacturing facility due to COVID-19 travel restrictions.

FDA has also issued a steady stream of guidance documents to help companies navigate new challenges brought on by the pandemic. For example, in June 2020, FDA issued “Good Manufacturing Practice Considerations for Responding to COVID-19 Infection in Employees in Drug and Biological Products Manufacturing,” a guidance document providing recommendations to drug and biological product manufacturers regarding manufacturing controls to prevent contamination, risk assessment of SARS-CoV-2 as it relates to drug safety or quality, and continuity of manufacturing operations. In August 2020, FDA released guidance titled “Manufacturing, Supply Chain, and Drug and Biological Product Inspections During COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Questions and Answers” to, among other things, clarify how FDA is handling site inspections and provide insight into those inspections that are deemed “mission critical.” In September 2020, FDA released “Resuming Normal Drug and Biologics Manufacturing Operations During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency,” which describes “how to evaluate and prioritize remediation of [current good manufacturing practice (CGMP)] activities that were necessarily delayed, reduced, or otherwise modified” during the COVID-19 pandemic “in order to maintain production and the drug supply.” In December 2020, FDA issued guidance titled “Conduct of Clinical Trials of Medical Products During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency,” which concerns safety and compliance with good clinical practice (GCP) in clinical trials conducted during COVID-19.

III. Legislation Relating to Biologics and Biosimilars

In 2020, lawmakers at the federal and state levels considered a variety of legislative proposals relating to biologics and biosimilars designed to improve patient access, encourage commercialization, and reduce costs.

A. Federal Legislation

On December 27, 2020, the President signed a second COVID-19 stimulus bill that included amendments to the BPCIA and updates to the Purple Book, which lists FDA-licensed biological products, including licensed biosimilar and interchangeable products, and their reference products. The amendments bring the Purple Book closer to the analogous Orange Book for small molecule drugs. In particular, under the new amendments, reference product sponsors (RPSs) are required to provide FDA with copies of any patent lists, along with patent expiration dates, within 30 days of when they were first provided to biosimilar applicants as part of the patent dance (pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(3)(A) or (l)(7)). FDA is then required to include this patent information in a public “searchable, electronic” database (i.e., the Purple Book), along with the following information about each approved biologic product: nonproprietary name, date of licensure and application number, licensure and marketing status, and exclusivities.

2020 also saw several legislative proposals directed to biosimilars focused primarily on improving access to biosimilars and reducing patient costs for biologic drugs, including insulins. While this legislation was not enacted by the 116th Congress, it provides insight into those issues that may be the focus of future legislation.

For example, in March 2020, representatives Tony Cárdenas (D-CA), Richard Hudson (R-NC), Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA), and Angie Craig (D-MN) introduced the Increasing Access to Biosimilars Act of 2020 (H.R. 6179). In July 2020, Senators John Cornyn (R-TX) and Michael Bennet (D-CO) introduced a companion bill with the same name (S. 4134). These bills would have directed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to implement a “shared savings” model to encourage physicians to prescribe lower-cost biosimilars by offering providers a percentage of any net savings realized resulting from their efforts to reduce healthcare spending by patients.

Also in March 2020, the ACCESS for Biosimilars Act of 2020 (S. 3466) was introduced by Senators Martha McSally (R-AZ) and Doug Jones (D-AL). This bill would have waived all out-of-pocket expenses for biosimilar products for beneficiaries of Medicare Part B programs for the first 5 years that a biosimilar is on the market. This was a companion bill to H.R. 4597, introduced in the House in October 2019.

In September 2020, Representative Glenn Grothman (R-WI) introduced a new bill, the Biosimilar Insulin Access Act of 2020 (H.R. 8190), that would have allowed for biosimilar insulins to automatically be granted interchangeability designations to their reference products.

B. State Legislation

While many states have enacted laws directed to biosimilars, specifically future interchangeables, California has enacted a number of additional unique laws. In particular, California recently enacted two health care laws, AB 824 and SB 852, with the stated goal of reducing drug prices.

On January 1, 2020, California Assembly Bill 824 (AB 824) went into effect. This first-of-its-kind law, signed by California Governor Gavin Newsom in October 2019, regulates anti-competitive patent settlements, sometimes referred to as “pay-for-delay” agreements, when brand name pharmaceutical companies or RPSs pay generic drug or biosimilar product manufacturers to slow down or stop lower-cost medications from entering the market. The most notable feature of California’s new law is its presumption that such settlements are anticompetitive and unlawful if the generic or biosimilar receives “anything of value.” This presumption is a departure from the traditional framework for analyzing the legality of patent settlements set forth by the Supreme Court in the 2013 case, FTC v. Actavis, under which an antitrust plaintiff bears the burden of proof. In addition, AB 824 also provides that the State of California may obtain civil penalties for violations by a fine of “an amount up to three times the value received by the party that is reasonably attributable to the violation” or $20 million, whichever is greater. The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) has challenged AB 824 as unconstitutional and preempted by federal law.[6]

In September 2020, Governor Newsom signed into law the California Affordable Drug Manufacturing Act of 2020 (SB 852), which would allow the state’s Health and Human Services Agency to contract with drug manufacturers and suppliers to produce and distribute its own label of biosimilars, biosimilar insulins, and generic drugs. In a statement announcing the new legislation, Governor Newsom said:

The cost of health care is way too high. Our bill will help inject competition back into the generic drug marketplace – taking pricing power away from big pharmaceutical companies and returning it to consumers . . . California is using our market power and our moral power to demand fairer prices for prescription drugs. I am proud to sign this legislation affirming our ground-breaking leadership in breaking down market barriers to affordable prescription drugs.

IV. BPCIA Litigation

Below, we briefly summarize overall statistics regarding BPCIA district court litigation to-date, and in the subsequent sections, we review (A) ongoing BPCIA district court cases, (B) BPCIA district court cases that settled in 2020, and (C) newly decided BPCIA appeals. We also identify several other Federal Circuit appeals that bear on biologics and biosimilars.

Since the BPCIA’s enactment in 2010, over 45 BPCIA cases have been filed in district courts.[7] (See Figure 2.) Amgen (with 16 cases) and Genentech (with 15 cases) are the most active plaintiffs and together account for the plaintiff side in more than half of all BPCIA litigation. Amgen is also the most common BPCIA defendant (with 8 cases), while Celltrion (defendant in 7 cases) and Sandoz (defendant in 6 cases) are not far behind.

BPCIA litigation has involved biosimilars of nine different reference products: Remicade®, Neulasta®, Neupogen®, Avastin®, Herceptin®, Rituxan®, Humira®, Enbrel®, and Epogen®. Unsurprisingly, these mirror the nine reference products for which there are FDA-approved biosimilars (see Section I, above).

In 2019, BPCIA district court filings began to decrease, and 2020 continued this trend. (See Figure 2.) Whereas 2018 had a record 12 BPCIA district court filings, 2019 had five, and 2020 had only four. We now turn to these four new cases and other recent litigation activity.

A. Ongoing BPCIA District Court Litigation

All four BPCIA cases filed in 2020, identified in Table 4, are currently ongoing.

Table 4. BPCIA Cases Filed in 2020

| Case Name | Court | Filing Date | Biosimilar at Issue | Reference Product at Issue | # of Asserted Patents |

| Amgen v. Hospira (1:20-cv-00201) |

D. Del. | 2/11/2020 | Nyvepria™ | Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim) |

1 |

| Amgen v. Hospira (1:20-cv-00561) |

D. Del. | 4/24/2020 | Nivestym® | Neupogen® (filgrastim) |

1 |

| Genentech v. Samsung Bioepis (1:20-cv-00859) |

D. Del. | 6/28/2020 | SB8 | Avastin® (bevacizumab) |

14 |

| Genentech v. Centus/Fujifilm (2:20-cv-00361) |

E.D. Tex. | 11/12/2020 | FKB238 | Avastin® (bevacizumab) |

10 |

In addition, two cases filed prior to 2020 remain ongoing:

- Amgen v. Hospira (18-cv-01064 D. Del.); Neupogen®/Nivestym®

- Immunex v. Samsung Bioepis (19-cv-11755 D.N.J.); Enbrel®/Eticovo™

We discuss each ongoing BPCIA district court case briefly below.

Amgen v. Hospira (20-cv-00201 D. Del.)

This case involves Hospira’s biosimilar of Amgen’s Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim). Amgen filed a complaint against Hospira and Pfizer on February 11, 2020, asserting U.S. Patent No. 8,273,707 (the ’707 patent), which is directed to methods of protein purification requiring a certain combination of salts at certain concentrations. (Dkt. 1 at 2, 10–12.) Amgen previously asserted this patent in BPCIA litigation against two other biosimilar developers, Coherus and Mylan, and both of those cases were resolved in 2019. The District of Delaware dismissed the Coherus case based on prosecution history estoppel barring Amgen from asserting infringement under the doctrine of equivalents against different combinations of salts than those in the claims of the ’707 patent, and the Federal Circuit affirmed on appeal. Amgen v. Coherus, No. 17-cv-00546, 2018 WL 1517689, at *1 (D. Del. Mar. 26, 2018), aff’d, 931 F.3d 1154 (Fed. Cir. 2019). Shortly after the Coherus decision, the parties in the Mylan case (17-1235 W.D. Pa.) stipulated to non-infringement.

In the current case, Hospira and Pfizer moved to dismiss, arguing that there is no literal infringement because (1) the accused process uses salt concentrations below those claimed in the ’707 patent (as properly construed in light of alleged disclaimers in the prosecution history), and (2) prosecution history estoppel precludes Amgen from asserting infringement under the doctrine of equivalents against different concentrations of the claimed salts for the same reasons as in the Coherus case. (Dkt. 19 at 1–4.) In opposition, Amgen argued that the Coherus decision “was based on the identity of the salts employed, not their concentration.” (Dkt. 28 at 1–2, 6.) Amgen also argued that a finding of non-infringement would be premature at the pleading stage because of outstanding claim construction and factual issues, such as the claim construction of “about 0.1M.” (Id. at 4.) Pfizer, in reply, contested Amgen’s positions. (See Dkt. 31.)

The motion to dismiss is pending, and the parties are currently engaged in fact discovery and claim construction briefing. A jury trial is set for July 11, 2022. (Dkt. 33.)

Amgen v. Hospira (20-cv-00561 D. Del.)

This case involves a biosimilar to Amgen’s Neupogen® (filgrastim) and is a follow-on to litigation already pending between the same parties in the District of Delaware (18-cv-01064, discussed below). This case involves a newly issued patent—U.S. Patent No. 10,577,392—asserted against the same Neupogen® biosimilar. (Dkt. 1 at 3.) The ’392 patent is directed to “methods of purifying proteins used in the manufacture of a biological product.” (Id.) In its complaint, Amgen alleges that it timely disclosed the ’392 patent by providing a supplement to its 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(3)(A) list under § 262(l)(7). (Id. at 3, 12, 18.) Amgen alleges that Hospira and Pfizer failed to comply with § 262(l)(7), however, because they did not provide Amgen “a statement . . . in accordance with paragraph (3)(B)” within 30 days of Amgen providing its supplement, and as of the filing date of the complaint, Hospira and Pfizer still had not provided the (3)(B) statement. (Id. at 18.)

On June 24, 2020, the court issued an oral order, denying Amgen’s motion to consolidate this case with the pending 2018 case. The court stated that it would not “consolidate this action with any other action absent Defendants’ agreement.” The court explained:

Plaintiffs filed the 18-1064 action on July 18, 2018. It waited until April 24, 2020 to file the instant action. Defendants reasonably agreed to consolidate the two cases if the parties agreed to use in the consolidated case the same experts employed by the parties in 18-1064. Plaintiffs refused to agree to this request, and therefore Plaintiffs should bear the consequences of litigating separately an action it filed almost two years after it filed 18-1064.

On January 7, 2021, the court granted in part Hospira and Pfizer’s motion to stay this case until the pending 2018 case is resolved. (Dkt. 30.) The court granted the stay because: (1) the two matters involve “identical parties, identical accused acts of infringement, the same accused processes, and related patents with . . . overlapping claim terms,” and thus a stay “will likely simplify the issues in question and trial of the case”; (2) fact discovery has not yet begun and no trial date has been set in the instant case, whereas the 2018 case is scheduled for a jury trial to begin on May 17, 2021; and (3) “a stay will neither unduly prejudice nor provide a clear tactical advantage to” Amgen. (Id. at 3–4.) The court noted that, to the extent Amgen argues that “Defendants’ ‘stated intent to price Nivestym® below other competitors enhances [the] potential for harm to [Amgen],’” Amgen can seek relief in the pending 2018 case for any price erosion because the two cases involve identical accused acts of infringement and the same accused process. (Id. at 5.) While granting the motion to stay, the court denied Hospira and Pfizer’s motion only “insofar as it seeks to stay pending a final resolution of C.A. 18-1064 that includes all appeals.” (Id.)

Genentech v. Samsung Bioepis (20-cv-00859 D. Del.)

This case relates to Samsung Bioepis’ proposed biosimilar of Genentech’s Avastin® (bevacizumab). Samsung Bioepis is the third bevacizumab biosimilar developer against which Genentech has initiated BPCIA litigation, following litigation against Pfizer and Amgen, which settled in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The Amgen case (17-cv-01407, -01471, 19-cv-00602 D. Del.) is discussed below.

On June 28, 2020, Genentech filed a complaint against Samsung Bioepis, alleging infringement of 14 patents covering methods of manufacturing bevacizumab and methods of treating patients with bevacizumab. (Dkt. 1.) Genentech’s complaint also alleged that Samsung Bioepis’ patent dance exchanges were deficient for a number of reasons, such as failing to provide “other manufacturing information” under § 262(l)(2)(A) and failing to provide a “detailed statement that describes, on a claim by claim basis, the factual and legal basis of [its] opinion . . . that [the patents identified by Genentech are] invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the commercial marketing” of Samsung Bioepis’ SB8 product as required by § 262(l)(3)(B). (Id. at 6–7.)

Samsung Bioepis answered and counterclaimed on August 31, 2020, asserting an affirmative defense of invalidity (among others) and counterclaims for non-infringement and invalidity. (Dkt. 9.) Samsung Bioepis also alleged irregularities in the patent dance, such as Genentech supplementing its patent list under (l)(7) and then filing suit before Samsung Bioepis provided its statements regarding non-infringement, invalidity, and unenforceability. (Id. at 59.)

On September 21, 2020, Genentech filed a motion to dismiss and strike Samsung Bioepis’ counterclaims and third affirmative defense, arguing that Samsung Bioepis cannot pursue patent invalidity arguments that it did not identify in its patent dance disclosures. (Dkt. 12 at 1.) In Genentech’s filings in support of its motion and in Samsung Bioepis’ opposition, the parties dispute the breadth and import of the court’s decision in Genentech v. Amgen, 17-cv-01407, 2020 WL 636439, at *4–5 (D. Del. Feb. 11, 2020) (discussed below), which held that Amgen was not limited to its invalidity positions set forth during the patent dance. For example, Genentech argues that a biosimilar should not be able to expand its invalidity theories absent good cause and that failing to present invalidity arguments during the dance can result in “forfeiture.” (Dkt. 12 at 5.)

The court has not yet ruled on the motion to dismiss and strike. A jury trial is set for July 10, 2023.

Genentech v. Centus/Fujifilm (20-cv-00361 E.D. Tex.)

This is the first BPCIA litigation filed in the Eastern District of Texas and the first BPCIA litigation involving Centus and its co-defendants Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics Co., Ltd., Fujifilm Corp., and Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd. This case involves Centus’ proposed biosimilar, FKB238, referencing Genentech’s Avastin® (bevacizumab). Centus is the fourth bevacizumab biosimilar developer against which Genentech has initiated BPCIA litigation, following litigation against Pfizer, Amgen, and Samsung Bioepis.

On November 12, 2020, Genentech filed a complaint, alleging infringement of 10 patents covering methods of manufacturing bevacizumab and methods of treating patients with bevacizumab. (Dkt. 1.) Genentech also alleged that Centus violated certain provisions of the BPCIA’s patent dance—for example, Genentech alleged that Centus failed to provide “other information that describes the process or processes used to manufacture the biological product that is the subject of such application,” as required by 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(2)(A). (Id. at 6–7.) Genentech also alleged that Centus’ “detailed” invalidity statements “provided only conclusory assertions that the patents identified by Genentech pursuant to . . . § 262(l)(3)(A) were invalid.” (Id. at 7–8.)

Centus has not yet responded to Genentech’s complaint.

Amgen v. Hospira (18-cv-01064 D. Del.)

This case involves Nivestym®, Hospira and Pfizer’s biosimilar of Amgen’s Neupogen® (filgrastim). Amgen alleged infringement of one patent, U.S. Patent No. 9,643,997, which is directed to protein purification. (Dkt. 1 at 3.)

The parties are currently engaged in supplemental expert discovery on Hospira and Pfizer’s on-sale bar and public use defenses, and the court has resolved two discovery disputes this year stemming from these issues. A jury trial is scheduled for May 17, 2021. (Dkt. 152.)

Immunex v. Samsung Bioepis (19-cv-11755 D.N.J.)

This case involves Samsung Bioepis’ biosimilar Eticovo™ referencing Immunex’s Enbrel® (etanercept). Immunex asserted five patents against Samsung Bioepis. (Dkt. 1 at 3.) These patents overlap with those asserted against Sandoz, and the Federal Circuit recently affirmed that Sandoz failed to prove two of those patents were invalid or unenforceable, as discussed below (CAFC 20-1037).

On January 8, 2020, the court entered a consent injunction order that prohibits Samsung Bioepis from making, using, importing, offering to sell, or selling “Bioepis’ Etanercept Product or any other product containing the fusion protein known as etanercept in the United States, except as allowed by [the] 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)” safe harbor. (Dkt. 113 at 1.) The basis for the order was “the Stipulation submitted to the Court on December 23, 2019, D.I. 105,” which is sealed and not publicly available. (Id.)

On January 15, 2020, the court ordered that this matter be administratively stayed consistent with the same sealed stipulation. (Dkt. 116.) The case remained administratively stayed through the remainder of 2020.

B. BPCIA Litigation Settled or Resolved in 2020

BPCIA cases settled or otherwise resolved in 2020 include:

- Genentech v. Amgen (17-cv-01407, -01471, 19-cv-00602 D. Del.); Avastin®/Mvasi™

- Genentech v. Amgen (18-cv-00924 D. Del.); Herceptin®/Kanjinti™

- Amgen v. Coherus (17-cv-00546 D. Del.); Neulasta®/Udenyca®

We discuss each of these resolved cases briefly below.

Genentech v. Amgen (17-cv-01407, -01471, 19-cv-00602 D. Del.)

This set of consolidated cases concerning Amgen’s proposed Avastin® (bevacizumab) biosimilar settled in July 2020. On July 7, 2020, the parties filed a joint stipulation of dismissal stating that they had entered into a settlement agreement and mutually agreed to voluntarily dismiss all claims and counterclaims with prejudice. (Dkt. 691.)

Before settlement, the district court issued a number of rulings in 2020 with potential applicability to other biosimilar litigation. For example, in March 2020, the court appointed a law professor as a special master to handle the parties’ requests to seal various court filings both in this case and the related Herceptin® case (18-cv-00924, discussed below). (See 17-cv-01407, Dkt. 659.) The Report and Recommendation, adopted by the court, acknowledged that the parties were “legally justified” in redacting “sensitive and confidential pre-litigation material reflecting the parties’ substantive exchanges during the non-public pretrial exchanges” under the BPCIA, among other sensitive material. (17-cv-01407, Dkt. 694 at 11–12.) In approving the parties’ redactions, the special master further acknowledged that in the “highly competitive pharmaceutical industry environment, even seemingly minor pieces of information about a pharmaceutical company can be valuable to its competitors.” (Id. at 14.)

The court also addressed matters of first impression regarding whether a biosimilar litigant is limited by its patent dance exchanges. In this case, Genentech asserted 26 patents based on Amgen’s submission of a biosimilar BLA for Mvasi™ referencing Genentech’s Avastin®. (See 17-cv-01407, Dkt. 626 at 1 n.1.) Amgen filed counterclaims and affirmative defenses alleging that all of the asserted patents were invalid and/or unenforceable. (17-cv-01407, Dkt. 124.) Genentech then moved to dismiss Amgen’s counterclaims and affirmative defenses based on Amgen’s alleged failure to comply with the patent dance under the BPCIA. (17-cv-01407, Dkt. 128, Dkt. 129.) As to Amgen’s declaratory judgment counterclaims, Genentech argued they were barred by 42 U.S.C. § 262(l)(9)(C) because Amgen did not provide information sufficient to describe its manufacturing process during the patent dance, and the BPCIA prevents a biosimilar that fails to adhere to subsection (2)(A) of the dance from “bring[ing] an action” for declaratory relief. (17-cv-01407, Dkt. 129 at 2–4.) Genentech also argued the defenses in Amgen’s invalidity counterclaims and affirmative defenses were “barred by the BPCIA to the extent they are based on invalidity, unenforceability, and noninfringement contentions that Amgen did not disclose to Genentech in the patent dance as required by § 262(l)(3)(B).” (17-cv-01407, Dkt. 626 at 8; see also Dkt. 129 at 5–9.)

On February 11, 2020, the court denied Genentech’s motion to dismiss. (17-cv-01407, Dkt. 626.) The court held that “the filing of counterclaims does not constitute ‘bringing an action’ and, is therefore not barred by § 262(l)(9)(C).” (Id. at 9.) Therefore, a biosimilar applicant is not precluded from bringing counterclaims of invalidity or noninfringement if it does not comply with or opts out of the patent dance. (See id. at 12–13.) The court also found that a biosimilar applicant is not precluded from raising a defense not disclosed during the patent dance. (Id.) The court noted that Genentech failed to “point to anything in the BPCIA or to case law interpreting the BPCIA that would support barring a biosimilar applicant from making in a BPCIA case contentions not disclosed in the patent dance.” (Id. at 10.) Genentech’s arguments were also foreclosed by § 262(l)(9)(B) and the Supreme Court’s decision in Sandoz, holding that the remedial provisions of § 262(l)(9)(B) and (9)(C) are the “exclusive remedies.” (Id. at 10–12.) Finally, Genentech’s “sole remedy” for Amgen’s alleged non-compliance in its (3)(B) statements was to “bring a declaratory judgment action for artificial infringement,” which Genentech had already done. (Id. at 12.) As noted above, Genentech and Samsung Bioepis are currently disputing the breadth of this ruling as it relates to invalidity theories not previously raised during the patent dance.

Genentech v. Amgen (18-cv-00924 D. Del.)

This case relating to Amgen’s Kanjinti™—a biosimilar of Genentech’s Herceptin® (trastuzumab)—also settled in July 2020. (Dkt. 555.)

Prior to settlement, in February 2020, the court denied Genentech’s motion to strike Amgen’s affirmative defenses and related counterclaims related to improper inventorship/derivation and unclean hands/inequitable conduct, which were added in response to Genentech’s Third Amended Complaint. (Dkt. 442 and 507.) Genentech argued that it had only amended the complaint “to address Amgen’s July launch of a Herceptin biosimilar product” and these new defenses and counterclaims were an end run around the scheduling order. (Dkt. 442 at 1.) The court nevertheless found that “Amgen’s filing of a responsive pleading as of right allows it to bring new counterclaims without regard to the scope of Genentech’s amendment.” (Dkt. 507 at 2.) The court noted that Genentech had “only itself to blame for enabling Amgen to assert the defenses and counterclaims to which Genentech now objects” and “Genentech’s decision to amend its complaint opened the door to Amgen filing its counterclaims.” (Id. at 3.)

Amgen v. Coherus (17-cv-00546 D. Del.)

This case involved Coherus’ biosimilar Udenyca® referencing Amgen’s Neulasta® (pegfilgrastim). Amgen had alleged infringement of its protein purification patent, U.S. Patent No. 8,273,707, under the doctrine of equivalents. (Dkt. 1 at 2–3, 9–11.) The district court dismissed the complaint, and the Federal Circuit affirmed that Amgen’s claims were barred by prosecution history estoppel. See Amgen v. Coherus, No. 17-cv-00546, 2018 WL 1517689, at *2–3 (D. Del. Mar. 26, 2018); Amgen v. Coherus, 931 F.3d 1154, 1156 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

In October 2019, Coherus filed a motion seeking to recover its attorneys’ fees. (Dkt. 92.) Coherus argued that this case was exceptional for a number of reasons, including the weakness of Amgen’s infringement case and Amgen’s insistence on litigating all the way through appeal. (Dkt. 92, at 6–11; Dkt. 97.) On November 30, 2020, the court denied Coherus’ motion for attorneys’ fees. (Dkt. 98.) The court found that “Amgen’s litigation positions were not exceptionally weak,” despite the fact that case was dismissed on a Rule 12(b)(6) motion; “Amgen’s conduct during the ‘patent dance’ did not amount to a misuse of that mechanism”; and there was “no evidence whatsoever that Amgen pursued its appeal—which was its right to pursue—in bad faith,” especially since the Federal Circuit heard oral argument and then designated its decision “precedential.” (Id. at 4–5, 7–8.)

Other District Court Litigation – Coherus v. Amgen (19-cv-00139 D. Del.)

The first biosimilar versus biosimilar case, Coherus v. Amgen, was filed and dismissed in 2019. This suit concerned two biosimilar versions of AbbVie’s Humira® (adalimumab) reference product—Coherus’ CHS-1420 and Amgen’s Amjevita™. Coherus alleged infringement of four formulation patents based on Amgen’s “actively offering for sale and selling Amjevita™ throughout Europe” and “actively manufacturing Amjevita™ in the United States for sale in Europe.” (Dkt. 7 at 4–5.) The parties stipulated and agreed to dismissal of this case in November 2019. (Dkt. 52.)

In December 2019, Amgen filed a motion to declare this case exceptional under 35 U.S.C. § 285 and award Amgen attorneys’ fees. (Dkt. 55.) Amgen alleged that Coherus “wrongful[ly], continued maintenance of this action between June 5, 2019—by which time Coherus knew or reasonably should have known that its infringement claims were baseless—and October 17, 2019, when Coherus first informed Amgen that Coherus intended to dismiss its claims.” (Dkt. 59 at 1.)

On June 11, 2020 the court denied Amgen’s motion for attorneys’ fees, finding that “Coherus’ position regarding Amgen’s Section 273 defense during the relevant time period was not so unreasonable as to warrant an award of exceptional case status pursuant to Section 285” and that “Coherus’ continued maintenance of the litigation for the period from June 5, 2019 to October 17, 2019 does not warrant a finding of exceptional case status.” (Dkt. 72 at 11–12.) The court noted that “[t]he record does not support Amgen’s position that Coherus took an unnecessary length of time to evaluate the merits of Amgen’s prior use defense,” and that “[t]he record also reflects that Amgen’s aggressive litigation strategy added to the expenses incurred while Coherus evaluated the merits of the prior use defense.” (Id. at 12.)

C. BPCIA Federal Circuit Appeals Decided in 2020

The Federal Circuit issued decisions in several BPCIA cases in 2020, and we discuss these decisions below. By the end of 2020, there were no BPCIA appeals pending before the Federal Circuit.

Janssen v. Celltrion (CAFC 18-2321, 18-2350)

At the district court, Janssen alleged that the cell culture media used by Celltrion to produce its Remicade® biosimilar infringed U.S. Patent No. 7,598,083 under the doctrine of equivalents. (17-cv-11008 D. Mass., Dkt. 1 at 12, 18–22.) Janssen’s doctrine of equivalents theory accounted for “at least twelve differences in concentration” in the claimed cell media component ranges. (CAFC 18-2321, Opening and Response Brief of Cross-Appellants at 3.) In July 2018, the district court granted Celltrion’s motion for summary judgment of non-infringement based on Celltrion’s ensnarement defense. Janssen v. Celltrion, No. 17-cv-11008, 2018 WL 10910845 (D. Mass. July 30, 2018), aff’d, 796 F. App’x 741 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

On appeal Janssen argued that the district court erred in the analysis by (1) impermissibly using hindsight to find that a hypothetical claim covering Celltrion’s cell culture medium would have been obvious; (2) failing to find Celltrion’s arguments regarding ensnarement legally baseless where Celltrion failed to offer any motivation to choose and modify the prior art references; and (3) failing to draw reasonable inferences in Janssen’s favor (e.g., teaching away from using ferric ammonium citrate as an ingredient in a cell culture medium and evidence of copying) in its summary judgment analysis. (CAFC 18-2321, Brief for Appellant at 2–5.) In February 2019, Celltrion responded and cross-appealed, arguing that “Janssen’s main arguments on appeal are narrow and unsound legal arguments,” and that Janssen lacked standing because not all co-owners of the ’083 patent were joined as plaintiffs. (CAFC 18-2321, Opening and Response Brief of Cross-Appellants at 3–7.)

On March 5, 2020, the Federal Circuit issued a Rule 36 affirmance of the district court’s grant of summary judgment, concluding the case in Celltrion’s favor. Janssen v. Celltrion, 796 F. App’x 741 (Mem), 2020 WL 1061676 (Fed. Cir. 2020). Celltrion had previously launched its Remicade® biosimilar Inflectra® in 2016.

Amgen v. Hospira (CAFC 19-1067, 19-1102)

In September 2017, a jury awarded Amgen $70 million in reasonable royalty damages based on Hospira’s infringement of U.S. Patent No. 5,856,298 in relation to a biosimilar of Amgen’s Epogen® (epoetin alfa). (15-cv-00839 D. Del.) This was the first BPCIA damages award. The patent was expired by the time of trial, and the biosimilar was neither approved nor launched at the time of the award. The jury awarded the damages for the manufacture of batches not covered by the safe harbor of 35 U.S.C. § 271(e). Amgen v. Hospira, 336 F. Supp. 3d 333, 340–45 (D. Del. 2018), aff’d, 944 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2019). The jury also found that Hospira did not infringe U.S. Patent No. 5,756,349. Id. at 359–61. In ruling on post-trial motions, the District of Delaware upheld the jury verdict. Id. at 344–45, 361, 366. Hospira appealed.

On December 16, 2019, the Federal Circuit affirmed. Amgen v. Hospira, 944 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2019). As to the safe harbor defense, the court found that the jury instructions were not legally erroneous. Id. at 1338–39. The court stated that “the patented inventions are Amgen’s claimed methods of manufacture” and the “accused activity is Hospira’s use of Amgen’s claimed methods of manufacture,” so “[t]he relevant inquiry, therefore, is not how Hospira used each batch it manufactured, but whether each act of manufacture was for uses reasonably related to submitting information to the FDA.” Id. The court also found that substantial evidence supported the jury’s finding that certain batches were not protected. Id. at 1339–40. For example, evidence was submitted that Hospira was not required by FDA to manufacture additional batches after 2012. Id. at 1340. It was also relevant, but not dispositive, that Hospira planned for some of the batches to “serve as commercial inventory,” even though Hospira later changed the designation of some of its batches after it received a Complete Response Letter from FDA. Id.

On January 15, 2020, Hospira petitioned for rehearing en banc on the safe harbor issues. The issue presented in the petition was “[w]hether 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1) provides a safe harbor against infringement of patents claiming a method of manufacture, when the product manufactured is used to generate information for submission to [FDA] in order to seek approval of a biosimilar drug.” (Petition for Rehearing En Banc at 1.) Hospira argued that the Federal Circuit panel’s opinion was contrary to precedent and rendered “the statutory protection for ‘making’ a drug [ ] illusory for a large subset of the patents available to be asserted under the BPCIA.” (Id. at 4.) On February 27, 2020, Amgen responded that “[t]he panel did not announce a special Safe Harbor rule for process patents,” and “rather than use ‘how’ or ‘why,’ the panel stated the issue in the language of the statute: ‘whether each act of manufacture was for uses reasonably related to submitting information to the FDA.’” (Response to Petition for Rehearing En Banc at 2, 10.) On March 16, 2020, the Federal Circuit denied Hospira’s petition for rehearing en banc without issuing an opinion on the merits.

Genentech v. Amgen (CAFC 19-2156)

This appeal relates to the District of Delaware’s denial of preliminary injunctive relief (18-cv-00924). The biosimilar in this case—Kanjinti™ (trastuzumab-anns), a biosimilar of Herceptin®—launched in July 2019 shortly after the district court’s decision. In this appeal, Genentech argued that the district court erred by (1) “inferring that Genentech will not suffer irreparable harm because it waited to seek preliminary injunctive relief until Amgen affirmatively decided to launch [Kanjinti],” and (2) “adopting a categorical rule that licensing of future activity negates irreparable harm from present infringement.” (Non-Confidential Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant at 25, 35.) The Federal Circuit issued a Rule 36 affirmance on March 6, 2020. Genentech v. Amgen, 796 F. App’x 726 (Mem), 2020 WL 1081707 (Fed. Cir. 2020). Shortly thereafter, in July 2020, the district court litigation settled, as discussed above.

Genentech v. Immunex/Amgen (CAFC 19-2155)

The appeal in this case also relates to the District of Delaware’s denial of preliminary injunctive relief (19-cv-00602 discussed above). The biosimilar in this case—Mvasi™ (bevacizumab-awwb), a biosimilar of Avastin®—also launched in July 2019 shortly after the district court’s decision. In this appeal, the issue was whether Amgen was required to provide a new notice of commercial marketing for its supplemental BLAs for Mvasi™. (Corrected Non-Confidential Opening Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant at 1–3.) At the district court and on appeal, Genentech argued that, although Amgen served a notice of commercial marketing pursuant Section 262(l)(8)(A) in 2017, Amgen was required to provide a new notice for each subsequent supplemental BLA. (Id. at 10–11.) Genentech argued that because Amgen did not provide notice for its supplemental BLA, Amgen was barred from commercially marketing its FDA-approved biosimilar until 180 days after it served such notice. (Id. at 12–13.)

On July 6, 2020, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial of preliminary injunctive relief, holding that “[a] biosimilar applicant that has already provided Section 262(l)(8)(A) notice [of commercial marketing] regarding its biological product need not provide another notice for each supplemental application concerning the same biological product.” Genentech v. Immunex, 964 F.3d 1109, 1112 (Fed. Cir. 2020). The court explained that “[t]he statute makes clear that the biosimilar applicant must provide notice to the reference product sponsor prior to commercially marketing the biological product.” Id. at 1111. The court further explained:

Amgen notified Genentech of its intent to commercially market its biological product, Mvasi on October 6, 2017. Despite its later supplements to its applications adding a manufacturing facility and changing its drug product label, Amgen’s biological product, Mvasi, did not change. Genentech, therefore, had notice of Amgen’s intent to commercially market Mvasi as required under Section 262(l)(8)(A) as early as October 6, 2017.

Id.

As discussed above, following the Federal Circuit’s decision, the district court litigation settled on July 7, 2020.

Immunex v. Sandoz (CAFC 20-1037)

This appeal involved two patents related to Sandoz’s Enbrel® biosimilar. (See 2-16-cv-01118 D.N.J.) The two patents, originally prosecuted in 1995, were set to expire in 2028 and 2029. Sandoz did not contest infringement but challenged the validity of the patents under multiple theories. On August 9, 2019, the district court held that the patents were not invalid. Immunex v. Sandoz, 395 F. Supp. 3d 366 (D.N.J. 2019), aff’d, 964 F.3d 1049 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

On appeal, Sandoz challenged the district court’s obviousness-type double patenting, written description, and obviousness analyses. On July 1, 2020, the Federal Circuit affirmed. Immunex v. Sandoz, 964 F.3d 1049 (Fed. Cir. 2020). In particular, the court held that the patents were not invalid for obviousness-type double patenting because there was no common ownership with other Immunex patents, the patents-in-suit were assigned to Roche, and Immunex did not obtain “all substantial rights.” Id. at 1057. The court found Immunex did not obtain “all substantial rights” because Roche had a secondary right to enforce the patents, and Roche had the “right to veto any assignment of Immunex’s interest.” Id. at 1061–62. The Federal Circuit also rejected Sandoz’s arguments on written description and obviousness. Id. at 1065–68.

Judge Reyna, who dissented, would have found the patents invalid for obviousness-type double patenting. Id. at 1068. Judge Reyna contended that “the majority permits the type of gamesmanship it sought to prevent—gamesmanship in prosecution which could result in unjustified extension of patent rights.” Id. at 1069. In particular, Judge Reyna would have interpreted the “2004 Accord & Satisfaction between Roche . . . and Immunex . . . as an effective assignment of the patents-in-suit to Immunex” and therefore “would hold that Immunex is a common owner for obviousness-type double patenting purposes.” Id. at 1068. Judge Reyna “would also hold that Immunex’s patents-in-suit are invalid for obviousness-type double patenting in view of Immunex’s previously issued U.S. Patent No. 7,915,225 under the one-way test.” Id.

On July 31, 2020, Sandoz filed a petition for rehearing en banc on obviousness-type double patenting. The issue presented in the petition was whether “[a] party that obtains an exclusive license conveying ‘all substantial rights’ to a patent, including the right to control prosecution, is effectively that patent’s owner for purposes of obviousness-type double patenting” and whether “a party [may] nonetheless avoid becoming an effective owner under the all-substantial-rights test, and thereby evade double-patenting scrutiny, merely by leaving the nominal owner with a theoretical secondary right to sue, which the licensee can prevent from ever ripening by issuing a royalty-free sublicense.” (Petition for Rehearing En Banc at vi.) On September 29, 2020, the Federal Circuit denied Sandoz’s petition for panel rehearing and rehearing en banc, concluding the case in Immunex’s favor. Sandoz has until March of 2021 to seek Supreme Court review of this case.

D. Other Federal Circuit Appeals

Although not BPCIA decisions, several other Federal Circuit decisions issued or pending in 2020 may have implications in the biosimilars context. We briefly identify some of these decisions below.

In Amgen v. Sanofi (CAFC 20-1074), currently pending before the Federal Circuit, the court is assessing enablement and written description of claims directed to a genus of antibodies. Sanofi has asserted that “[t]he undisputed evidence established that making and using the full scope of Amgen’s functional genus claims requires undue experimentation under the Wands factors” and “millions of antibodies could potentially fall within the claims’ scope.” (Brief of Defendants-Appellees (Non-Confidential) (Corrected) at 17–19.) Oral argument was held by teleconference on December 9, 2020.

In Biogen MA Inc. v. EMD Serono, Inc., 976 F.3d 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s judgment as a matter of law of no anticipation for claims to methods of treatment using a recombinant polypeptide in light of a native form of the polypeptide. The court concluded that “[t]he district court’s refusal to consider the identity of recombinant and native IFN-β runs afoul of the longstanding rule that ‘an old product is not patentable even if it is made by a new process.’” Id. at 1332.

Finally, in Valeant Pharm. N. Am. LLC v. Mylan Pharm. Inc., 978 F.3d 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the Federal Circuit addressed venue in the Hatch-Waxman context, in particular where the artificial act of infringement occurs upon filing of an ANDA for venue purposes. The court found that “in cases brought under 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2)(A) [pursuant to the Hatch-Waxman Act], infringement occurs for venue purposes only in districts where actions related to the submission of an Abbreviated New Drug Application (‘ANDA’) occur, not in all locations where future distribution of the generic products specified in the ANDA is contemplated.” Id. at 1375.

V. Antitrust Litigation

As discussed above, while many biosimilars have successfully entered the U.S. market and gained significant market share through 2020, there have been some notable exceptions in Remicade® (infliximab), Enbrel® (etanercept), and Humira® (adalimumab) biosimilars. The disparity in success among the different biosimilars may be caused by a number of factors, but some have expressed a concern that the primary barrier is anticompetitive conduct by reference product sponsors. For example, a recent qualitative study of biosimilar manufacturer and regulator perceptions on intellectual property and abbreviated approval pathways for biosimilars reported that the “main intellectual property concern for biosimilars . . . was the large numbers of patents—sometimes called thickets—that originator biologic manufacturers obtain relating to their products.”[8]

Against this backdrop, a number of stakeholders have brought antitrust litigation against the RPSs for Humira® (AbbVie) and Remicade® (Janssen and Johnson & Johnson (J&J)). We review this litigation below.

Remicade® (infliximab) Antitrust Litigation

There are currently multiple antitrust lawsuits pending in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania against Johnson & Johnson (J&J) and its subsidiary Janssen concerning Remicade® (infliximab). In these cases, the plaintiffs have alleged that J&J and Janssen engaged in a scheme to protect Remicade® in violation of federal antitrust law and maintained market share and pricing for Remicade® through several anticompetitive devices, including exclusionary contracts, bundling, and coercive rebates.

The first case, brought by Pfizer (No. 17-cv-04180, E.D. Pa.), and a subsequent class action lawsuit by indirect purchasers (No. 17-cv-04326, E.D. Pa.) are in fact discovery, but have encountered delays due to COVID-19. Walgreen and Kroger’s case (No. 18-cv-02357, E.D. Pa.) is in early stages, since the district court had initially found the plaintiffs lacked standing due to contractual limitations, a decision reversed in February 2020 by the Third Circuit. Walgreen Co. v. Johnson & Johnson, 950 F.3d 195, 196 (3d Cir. 2020) (reversing because “[t]he antitrust claims are a product of federal statute and thus are extrinsic to, and not rights ‘under,’ a commercial agreement.”) On April 6, 2020, J&J and Janssen filed an answer to the complaint in the Walgreen and Kroger suit. Note that, on October 20, 2020, Rochester Drug Co-operative, Inc. filed a stipulation of voluntary dismissal in the direct purchaser action (No. 18-cv-00303, E.D. Pa.).

In re: Humira (Adalimumab) Antitrust Litigation, No. 19-cv-1873 (N.D. Ill.)

In March 2019, indirect purchasers of AbbVie’s blockbuster biologic, Humira® (adalimumab), brought an antitrust suit against AbbVie and Humira® biosimilar manufacturers in the Northern District of Illinois. (19-cv-01873, N.D. Ill.) The complaint alleged two antitrust theories. First, the plaintiffs alleged that AbbVie monopolized the market in violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act by constructing a “patent thicket” of “invalid, unenforceable, or noninfringed patents” around Humira® that blocked the entry of adalimumab biosimilar products. Second, the plaintiffs further alleged that AbbVie and several Humira® biosimilar manufacturers entered into anticompetitive “pay-for-delay” and geographic market allocation settlement agreements in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act.

In June 2020, U.S. District Judge Manish Shah dismissed the complaint without prejudice, finding that the plaintiffs alleged neither a cognizable antitrust violation nor antitrust injury. (Dkt. 170.) The court concluded that “the vast majority of the alleged scheme is immunized from antitrust scrutiny [e.g., under the Noerr-Pennington doctrine], and what’s left are a few sharp elbows thrown at sophisticated competitors participating in regulated patent and biologic-drug regimes.” (Id. at 31.) Further, AbbVie’s settlement agreements did not fit the model of “reverse payment” settlements found unlawful in the Supreme Court’s FTC v. Actavis decision, for example, because the “settlements . . . allow for early entry [into the U.S. market] without payment.” (Id. at 43.) And, in addition, the court found that the plaintiffs’ allegations of antitrust injury were “too speculative.” (Id. at 51.)

The plaintiffs appealed to the Seventh Circuit (20-2402). Appellants’ reply brief was filed on February 1, 2021, completing briefing. Several amicus briefs from interested parties, including trade organizations, public interest groups, and economics, law, business, and medical professors, have also been filed. Oral arguments are scheduled for February 25, 2021.

VI. Post-Grant Challenges at the PTAB

2020 was a slow year for biologics and biosimilars at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). Only two biologic inter partes review (IPR) petitions were filed in 2020, representing a sharp decline from a high of more than 80 petitions in 2017.

On January 3, 2020, Regeneron filed a petition for IPR against Kymab concerning a patent that claims a transgenic mouse that produces “reverse-chimeric” antigen-specific antibodies with human variable domains and mouse constant domains. (IPR2020-00389, Paper 2, at 1.) The PTAB denied institution on May 26, 2020. (Paper 7.) Regeneron had previously filed four other IPR petitions in 2019 challenging other Kymab patents relating to transgenic mice engineered to produce antibodies, and the PTAB denied institution in each of those IPRs as well. (Id. at 2.)

An additional IPR was filed in December against an Amgen biologic method patent. In addition, a post-grant review (PGR) was filed in December against SeaGen, Inc. related to Enhertu (trastuzumab deruxtecan). These are both still pending.

While there were not many biologic IPR filings in 2020, several disputes reached resolution this year, some of which are noted below.

- Cosentyx® (secukinumab): In February 2020, Novimmune and UCB settled two IPRs concerning composition and method of treatment claims covering Novimmune’s Cosentyx® (secukinumab) pre-institution. (IPR2019-01480, -01481.)

- Emgality® (galcanezumab): In February and March 2020, the PTAB invalidated claims in six patents asserted by Teva against Eli Lilly concerning Eli Lilly’s Emgality® (galcanezumab) (IPR2018-01422, -01423, -01424, -01425, -01426, -01427), while upholding the validity of claims in three other patents. (IPR2018-01710, -01711, -01712.)

- Soliris® (eculizumab): In May 2020, Amgen and Alexion settled three IPRs concerning method of treatment claims covering Alexion’s Soliris® (eculizumab) post-institution. (IPR2019-00739, -00740, -00741.) Amgen obtained a non-exclusive, royalty-free U.S. license and the ability to bring a biosimilar to market in March 2025.

- Amgen Manufacturing Patents: In June 2020, Amgen and Fresenius settled IPRs on two Amgen manufacturing patents. The parties settled Fresenius’ IPR challenging an Amgen patent related to methods for folding proteins pre-institution (IPR2020-00314), and the parties settled Fresenius’ IPR challenging an Amgen patent relating to methods of protein purification post-institution. (IPR2019-01183.)

In addition, the Federal Circuit in 2020 weighed in on several IPR appeals involving biologic products—in many cases affirming the PTAB’s final written decisions invalidating claims. For example:

- Genentech, Inc. v. Hospira, Inc., 946 F.3d 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (affirming IPR decision invalidating antibody manufacturing claims as anticipated and obvious and finding that retroactive application of IPR to invalidate patents issued prior to the America Invents Act did not violate the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause);

- Immunex Corp. v. Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC, 977 F.3d 1212 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (affirming IPR decision invalidating claims to isolated human antibodies for binding human IL-4 receptors as obvious);

- Genentech, Inc. v. Iancu, 809 F. App’x 781 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (affirming IPR decisions invalidating claims to methods of treatment using an anti-ErbB2 antibody);

- AbbVie Biotechnology, Ltd. v. United States, 789 F. App’x 879 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (issuing Rule 36 affirmance of IPR decisions invalidating three patents directed to adalimumab as obvious); and

- Biogen, Inc. v. Iancu, 831 F. App’x 506, 507 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (issuing Rule 36 affirmance of IPR decisions invalidating method of treatment claim covering rituximab).

VII. Conclusion

The year 2020 saw few new biosimilar approvals and a drop in biosimilars-related litigation. While the slowdown may be partially attributable to the COVID-19 global pandemic, it could also potentially represent a lull between a first phase of challenges to decades-old biologics and an anticipated second phase of challenges to newer biologics that are reaching the end of their twelve-year statutory period of exclusivity—as well as insulin and other biological products that are now deemed to be approved as BLAs.

Despite the slowdown in approvals and litigation, the U.S. biosimilars market continues to grow, with five new biosimilar product launches and reports showing increased uptake in biosimilars through 2020. FDA remained an active participant in the space, facilitating the transition of insulin and other “drugs” to regulation under the biologics statutory framework and providing new guidance on several different issues, such as biosimilarity, interchangeability, and promotional labeling and advertising. Federal and state lawmakers have also continued to consider legislation designed to improve patient access, reduce drug prices, and increase competition.

Several new developments may be in store for the U.S. biosimilars industry in 2021. FDA is now reviewing BLAs for biosimilars of reference products without previously approved biosimilars—such as Samsung Bioepis and Biogen’s SB11, a biosimilar referencing Lucentis® (ranibizumab). Insulin interchangeables may also be on the horizon, for example Semglee™. And, Amgen has announced that the newly approved Riabni™ (rituximab-arrx) will be available to the United States market in early 2021. On the litigation side, the Seventh Circuit will likely provide insight into the antitrust allegations asserted against AbbVie for its blockbuster Humira® biologic, and additional guidance may come from pending and future district court BPCIA litigations.

[1] Approval time is calculated from the first BLA submission date, not any resubmission date.

[2] The Fiscal Year for the Federal Government starts October 1 and ends September 30.

[3] See, e.g., Amgen’s 2020 Biosimilar Trends Report at https://www.amgenbiosimilars.com/-/media/Themes/Amgen/amgenbiosimilars-com/Amgenbiosimilars-com/pdf/USA-CBU-80723-2020-Amgen-Biosimilar-Trends-Report.pdf; October 2020 report from IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/biosimilars-in-the-united-states-2020-2024.

[4] Yazdany, Jinoos, “Failure to Launch: Biosimilar Sales Continue to Fall Flat in the United States,” Arthritis & Rheumatology, Vol. 72, No. 6, June 2020, pp. 870-873.

[5] Amgen’s 2020 Biosimilar Trends Report, available at https://www.amgenbiosimilars.com/-/media/Themes/Amgen/amgenbiosimilars-com/Amgenbiosimilars-com/pdf/USA-CBU-80723-2020-Amgen-Biosimilar-Trends-Report.pdf.

[6] AAM’s initial lawsuit concluded after the Ninth Circuit, in a July 2020 opinion, found AAM lacked standing. Ass’n for Accessible Medicines v. Becerra, 822 F. App’x 532 (9th Cir. 2020). On August 25, 2020, AAM filed a new complaint in the Eastern District of California challenging AB 824. (See 20-cv-01708-TLN-DB, E.D. Cal.) On September 14, 2020, AAM filed a new motion for a preliminary injunction, which remains pending. (Dkt. 15.) All deadlines and proceedings are stayed pending resolution of the preliminary injunction motion. (Dkt. 32.)

[7] Many of these cases involve the same parties and the same biosimilar products, so do not reflect unique disputes.

[8] Louise C. Druedahl et al., A Qualitative Study of Biosimilar Manufacturer and Regulator Perceptions on Intellectual Property and Abbreviated Approval Pathways, 38 Nature Biotechnology 1253, 1255 (Nov. 2020).

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.