Post-Grant Report

2019 Post-Grant Annual Report

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Senior Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

THE PATENT TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD (PTAB) REMAINS THE FORUM OF CHOICE FOR CHALLENGING THE VALIDITY OF PATENT CLAIMS.

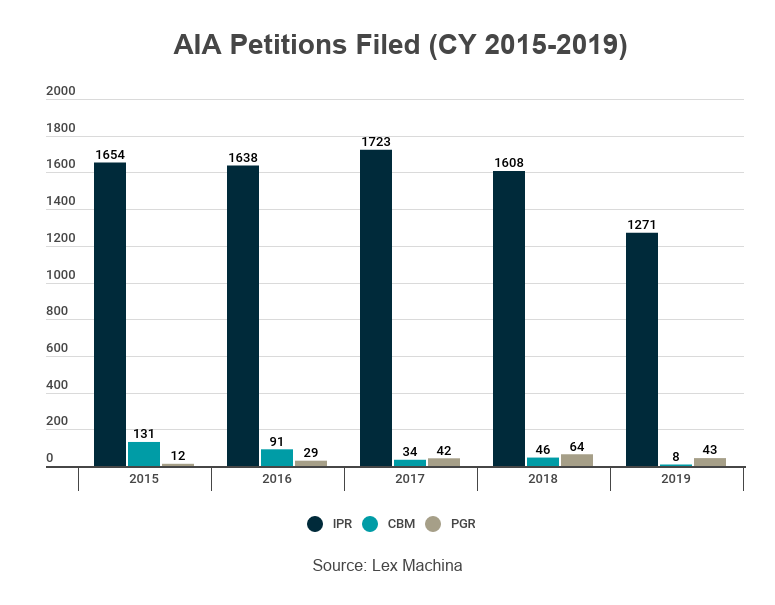

However, it is notable that a comparison of 2019 and 2018 statistics reveals about a 30 percent decline in filings. Under the guidance of its newly appointed chief judge, Scott Boalick, who assumed his new role in March 2019, the PTAB announced a new Pilot Program granting patent owners new options for motions to amend and a second update to the America Invents Act (AIA) Trial Practice Guide (TPG) relating to recent precedential decisions. Incidentally, 2019 also marked the eighth anniversary of the AIA. We saw important decisions from the Supreme Court in Return Mail—barring the federal government from initiating post-grant challenges—and from the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Arthrex, challenging the constitutionality of administrative patent judges.

The PTAB Bar Association continued its momentum and had another dynamic year, including its third Annual Conference in March as well as its second annual Leader Summit in November. Both conferences were well attended by practitioners, in-house counsel, and members of the bench. The association also submitted an amicus brief in the Supreme Court Click-to-Call case and released its inaugural report on Women at the PTAB, prepared by the association’s Women’s Committee. The fourth Annual Conference is scheduled for March 11-12, 2020.

Fish & Richardson’s 2019 Post-Grant Report takes a deep dive into the cases, trends, and statistics that shaped post-grant practice throughout the year and postulates how they may affect practitioners going forward.

When it comes to post-grant practice, Fish’s history and presence are unmatched: We have handled more cases at the PTAB than any other firm, our attorneys routinely craft new law at the Federal Circuit, we host the most innovative educational programs, and we are a founding and active member of the PTAB Bar Association. For more information, please contact practice group chairs Dorothy Whelan or Karl Renner, or visit fishpostgrant.com.

Trial Practice Guide Update

In 2019, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) published two updates to the PTAB’s Trial Practice Guide. First, in July, the USPTO published a substantive update to provide additional guidance about PTAB practice. Second, in November, the USPTO published a second edition of the practice guide to incorporate the August 2018 and July updates into the original August 2012 practice guide. The November update was largely clerical, as the second edition merely consolidates all updates into a single document and provides slight revisions to ensure consistency across all sections.

The July update largely revised the TPG to reflect precedential or informative decisions and other established developments that had occurred since the August 2018 update. Two of the more significant changes relate to claim construction and the procedure for evaluating multiple challenges to a single patent.

As to claim construction, the July update is noteworthy because it was the first update to address the USPTO’s change in the claim construction standard from the broadest reasonable interpretation to Phillips. The update explains how the PTAB strives to resolve claim construction issues before deciding whether to institute a review, and it requires a petitioner to include in the petition a statement identifying a construction the petitioner wishes to advance and any evidence that supports that construction. In fact, the update confirms that the petitioner can respond to claim constructions raised by the patent owner or the board but cannot raise new claim constructions that were not advanced in the petition.

The July update also provides guidance on how the PTAB will evaluate claim construction decisions made by a district court or the International Trade Commission. Although the standard is now the same and the board will consider decisions that are timely made of record, the board will not simply adopt constructions made in other forums. Rather, the board will make its own decisions on claim construction, taking into account the degree of similarity between the records in the different proceedings and whether the other construction is final.

With these updates, the board has expressed a clear desire for parties to advance claim construction positions early, and it expects parties to be candid about constructions offered in different forums. Indeed, the board strives to prevent situations where a party changes an interpretation based on arguments from the other party or developments in another forum. For these reasons, it is more important than ever to develop claim construction positions early and to coordinate claim constructions across proceedings involving the same patent.

As to multiple petitions, the July update confirms the board’s disfavor of multiple petitions against a single patent, explaining how the board generally considers a single petition sufficient to balance fairness, timing, and efficiency concerns of patent owners. The new guidance does not eliminate the potential for institution of multiple petitions, but it places the burden on the petitioner to explain why “more than one petition is necessary” and requires the petitioner to provide a ranking of petitions when multiple petitions are being filed.

To enable petitioners to meet this burden, the July update introduces a new procedure that allows petitioners to file a separate paper, limited to five pages, to rank the petitions and explain why the differences between the petitions justify institution of more than one. The update provides two examples of justifications for multiple petitions: (1) “when the patent owner has asserted a large number of claims in litigation” or (2) “when there is a dispute about priority date requiring arguments under multiple prior art references.”

Patent owners are granted a separate, five-page paper to respond to petitioner justifications and explain why more than one petition is unnecessary. A patent owner can avoid multiple petitions by offering stipulations that resolve a disputed issue, such as stipulating that it will not contest a dispute about a priority date that differentiates two petitions.

With these changes, the board is seeking to limit multiple attacks against a single patent. Although the board’s jurisprudence on discretionary denial was already trending in this direction, the July update confirms that the board places the burden on petitioners to justify why multiple petitions against a single patent are needed.

The Rise of PTAB Precedential Opinion Panels

In 2019, the PTAB issued the first precedential decisions from the Precedential Opinion Panel. The USPTO revised its standard operating procedures in the last half of 2018, which included a new path for establishing precedential decisions that have binding authority on future PTAB panels. In particular, the mechanism of the Precedential Opinion Panel was intended to serve the USPTO’s “interest in creating binding norms for fair and efficient Board proceedings, and for establishing consistency across decision makers under the [AIA].” See PTAB Standard Operating Procedure 2, p. 2. The Precedential Opinion Panel will normally, by default, consist of the director, the commissioner for patents, and the chief judge.

In 2019, the director acted in three cases to review earlier board decisions for purposes of providing a Precedential Opinion Panel decision (POP decision). The first POP decision was provided in March and addressed the issue of “same party joinder.” See Proppant Express Investments, LLC v. Oren Technologies, LLC, IPR2018-00914, Paper 38, 3-5 (Mar. 13, 2019). The second POP decision, issued in August, addressed the issue of whether the one-year window to file a petition is triggered by a deficient litigation complaint. See GoPro, Inc. v. 360Heros, Inc., IPR2018-01754, Paper 38, 2 (Aug. 23, 2019). Last, a third POP decision addressed the question of what must be shown in a petition to sufficiently establish that a textbook or other non-patent reference qualifies as a “printed publication.” See Hulu, LLC et al. v. Sound View Innovations, LLC, IPR2018-01039, Paper 20 (Dec. 20, 2019). In all these cases, the Precedential Opinion Panel acted in response to a request for rehearing from a party in an inter partes review (IPR) proceeding, provided notice to the public that the Precedential Opinion Panel would act in that particular adjudication, invited briefing from the parties and other amici, and participated in an oral hearing.

Even though such POP decisions are binding on PTAB panels in future cases, there remains a lively debate as to whether the Federal Circuit should afford deference to such “precedential” decisions—namely, a level of deference often referred to as Chevron deference. Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984). Under this doctrine, a court is obligated to defer to an agency’s rules that interpret an ambiguous statute if the agency’s interpretation is reasonable. United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S., 218, 226-27 (2001). Recently, a Federal Circuit panel voiced concerns about whether such POP decisions should be given deference during appellate review because they are not the result of formal notice-and-comment procedures. See Facebook, Inc. v. Windy City Innovations, LLC, Appeal No. 2018-1400 (Fed. Cir., oral hearing Aug. 6, 2019) (questioning the effect of the POP decision in Proppant Express). In particular, U.S. Circuit Judge Plager commented during oral hearing that “[t]hey can’t get Chevron deference in any sense, so you should put that out of your mind.” Id. Additionally, Chief U.S. Circuit Judge Prost questioned why the USPTO had not yet intervened in this appeal, explaining that “I don’t understand why they haven’t intervened because there is a very important question of joinder here.” Id. Several days after the oral hearing, the Federal Circuit panel ordered additional briefing, including briefing from the USPTO on this specific issue.

The USPTO submitted a brief in September that explained why the decisions of the Precedential Opinion Panel should be entitled to Chevron deference. Namely, the USPTO cited the Supreme Court’s Mead decision to demonstrate that Congress can delegate authority (for an agency to make rules carrying the force of law and thus be entitled to Chevron deference) by giving the agency “power to engage in adjudication or notice-and-comment rulemaking.” Mead, 533 U.S. at 226-27. Here, such POP decisions were the result of the USPTO’s authority to “adjudicate” IPRs rather than conduct “notice-and-comment rulemaking,” and according to the USPTO’s argument, both are available options for establishing agency rules that are worthy of Chevron deference. The USPTO also reiterated the fact that the POP decision in Proppant Express occurred only after the USPTO provided notice to the public, invited briefing from the parties and other amici, and participated in an oral hearing. As such, the POP decisions issued after such adjudication should be accorded Chevron deference much like the decisions from the Board of Immigration Appeals and the National Labor Relations Board.

The responsive briefing contends that the Federal Circuit should offer no such deference to POP decisions. For example, the Windy City briefing contends that the AIA statutes provide an “express” delegation of rulemaking authority for the director to promulgate “regulations,” and that nothing in the statutes shows Congress intended to delegate “general rulemaking authority” (without the need for regulations resulting from publication in the Federal Register and notice-and-comment rulemaking). See 35 U.S.C. § 2(b)(2)(B). Additionally, the Windy City briefing argued that the particular POP decision at issue in this case (Proppant Express) is not entitled to deference because the language of the statute being interpreted (35 U.S.C. § 315(c)) was not ambiguous and did not require “agency expertise” that provided specialized guidance to the court.

A decision from the Federal Circuit in Windy City is expected in early 2020.

In summary, the rise of decisions from the Precedential Opinion Panel in 2019 achieved its goal of providing a higher level of predictability from future PTAB panels on issues of exceptional importance, but there are still meaningful questions as to whether the USPTO’s interpretation of the AIA statutes in such POP decisions will be accorded deference from reviewing courts.

Motions to Amend under the New Pilot Program

On March 15, 2019, the USPTO announced a one-year Pilot Program for amendment practice in AIA trial proceedings. See 84 Fed. Reg., 9,497. One hallmark feature of the Pilot Program is that a patent owner may choose to request the board’s nonbinding preliminary guidance on the likelihood that a motion to amend (MTA) will succeed. The patent owner may also choose to file a revised MTA after receiving the petitioner’s opposition brief and the board’s preliminary guidance.

The Pilot Program is applicable to proceedings instituted on or after March 15 and the board strictly enforced this threshold, discarding participation requests from patent owners instituted even a day beforehand. For qualifying patent owners, the Pilot Program provides two timelines: one premised on the patent owner defending his or her original MTA, and one premised on the patent owner filing a revised MTA. The timeline for the former is unchanged from the preexisting procedure, but the briefing available to the parties depends on the patent owner’s course of action. As to the latter, where the patent owner files a revised MTA, the schedule is expanded, moving the oral hearing back one month to accommodate a full suite of briefing from the parties. The subsequent deadlines are compacted, and the months leading up to the oral hearing are very busy for the parties. The same is true for the parties’ experts, with likely two, and maybe three, depositions warranted in an eight-week time frame. The board expects the parties to make their experts available for these depositions without delay and suggests scheduling ahead (i.e., before anticipated declarations are submitted) to accommodate the time crunch.

The board’s preliminary guidance document follows a standardized template that addresses each of the procedural and statutory issues relevant to an MTA—reasonable number of claims, responsiveness, enlargement, new matter, and patentability under §§ 101/102/103/112(b). The guidance reads very much like an institution decision, particularly as to the evaluation of any new prior art, and it addresses only the new features added by amendment.

Patent owners have thus far sought to take advantage of the Pilot Program’s new procedures, with the overwhelming majority requesting preliminary guidance and entering a revised MTA. The Board’s guidance thus far has been consistently favorable on the procedural issues but comparatively unfavorable on patentability. And this makes sense. After all, the patent owner is unlikely to have even seen, much less preemptively responded to, the petitioner’s new prior art.

Despite procedures that have been viewed by commentators as favorable to patent owners, the rate at which MTAs are being filed has not significantly increased since the implementation of the Pilot Program. The USPTO reported MTA filing rates hovering at around 9 percent for trials completed before the Pilot Program, and this level of activity seems to be holding steady. With no trials under the Pilot Program having yet reached a final written decision, it remains to be seen whether the grant rate for MTAs will increase from the 10 percent rate previously reported by the USPTO. Higher success rates may lead to more filings in the future if the Pilot Program is extended or permanently installed.

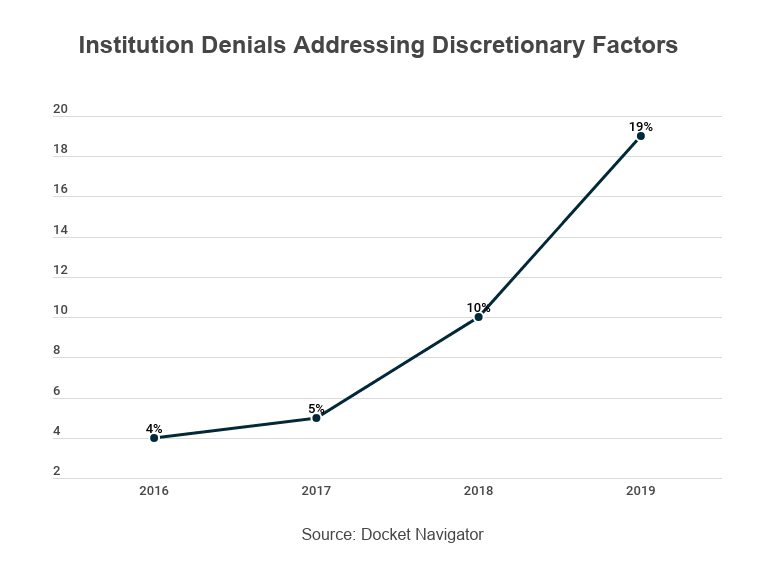

The Rise of Discretionary Denials

In 2019, the PTAB has continued the trend of exercising discretion to deny institution at an increasing rate and based on new reasons. Discretionary denials have been exercised sometimes despite the board’s finding that the petition establishes a reasonable likelihood that at least one claim is unpatentable or sometimes without the board conducting a substantive analysis of the petition. Such denials are most likely to occur in one of five possible situations, including:

- When multiple petitions are filed by the same petitioner.

- When different petitioners challenge the same patent.

- When the petition includes prior art or arguments previously presented.

- When there is late-stage, co-pending litigation.

- When a significant number of claims and/or grounds do not have a reasonable likelihood of prevailing.

The above categories for discretionary denials, representing those commonly encountered by post-grant practitioners today, indicate their evolution from the once-controversial but now-forgotten redundancy doctrine. The following chart shows the increasing trend of institution decisions where institution was denied and discretionary factors were discussed. (Note that the chart is based on institution decisions that both denied institution and discussed discretionary factors. Denial was not necessarily due to discretion in all cases.)

1. Multiple Petitions, Same Petitioner

Factors for determining whether multiple petitions on the same patent will be subject to a discretionary denial were outlined in General Plastic Industrial Co., Ltd. v. Canon Kabushiki Kaisha, IPR2016-01357, Paper 19 (PTAB Sep. 6, 2017), which was designated as precedential in October 2017.

The PTAB has continued to apply the General Plastic factors, and on July 15, the board introduced, in its updated third revision of the TPG, that “one petition should be sufficient to challenge the claims of a patent in most situations.” However, the TPG states that “the Board recognizes that there may be circumstances in which more than one petition may be necessary” and outlines a new requirement for petitioners filing two or more petitions challenging the same patent. Such petitioners, in either the petitions or in a separate paper (with a five-page limit) filed with the petitions, should identify:

(a) A ranking of the petitions in the order in which they wish the board to consider the merits if the board uses its discretion to institute any of the petitions.

(b) A succinct explanation of the differences between the petitions, why the issues addressed by the differences are material, and why the board should exercise its discretion to institute additional petitions if it identifies one petition that satisfies the petitioners’ burden under 35 U.S.C. § 314(a).

Thus, although the General Plastic factors were originally intended to target a specific type of petition, namely multiple petitions filed against the same patent by the same petitioner (referred to as “follow-on” petitions), more recent trends show that the scope of petitions that fall within the General Plastic discretionary denials has expanded, as illustrated by the new guidelines outlined by the updated TPG as well as the second category of discretionary denials discussed next.

2. Multiple Petitions, Different Petitioners

The PTAB opinion in Valve Corporation v. Electronic Scripting Products, Inc., IPR2019-00062, Paper 11 (PTAB Apr. 2, 2019), was designated precedential in 2019. This decision expands the General Plastic doctrine for applying a discretionary denial from a single petitioner to multiple petitioners under certain circumstances. In this case, Valve filed a petition challenging the validity of U.S. Patent No. 9,235,934, and the petition was denied under § 314(a) based on an earlier petition filed by a different petitioner, HTC America. HTC had filed an IPR petition against the ’934 patent, which was denied institution before Valve filed its petition against the same patent. The board denied Valve’s petition, arguing that it qualified as a follow-on petition because Valve challenged the same patent claims as HTC and the institution decision rendered against HTC’s petition would unfairly create a “road map” for Valve. The board has often considered the use of prior decisions as a road map to be an unfair advantage for petitioners because it allows petitioners to learn from prior decisions to find better prior art that invalidates the claims. In its decision, the PTAB stated that the General Plastic factors were not limited to reviewing the actions of a single petitioner but that a relationship between current and previous petitioners also can be considered. The board found that there was a “significant relationship” between Valve and HTC because they were both co-defendants in a district court litigation, and it determined that the applied General Plastic factors weighed against institution.

3. Discretionary Denials under § 325(d) for Prior Art Previously Presented

The PTAB exercises discretion under 35 U.S.C. §§ 314(a) and 325(d) to deny petitions when the prior art and arguments presented in the petition were already considered by the USPTO, such as during prosecution. The factors applied for discretionary denials based on previously asserted prior art are provided by decisions in Becton, Dickinson & Co. v. B. Braun Melsungen AG, IPR2017-01586, Paper 8 (PTAB Dec. 15, 2017), and Kayak Software Corp. v. IBM Corp., CBM2016-00075, Paper 16 (PTAB Dec. 15, 2016). The PTAB has continued to issue discretionary denials in such situations in cases including Aquestive Therapeutics, Inc. v. Neurelis, Inc., IPR2019-00450, Paper 8 (PTAB Aug. 1, 2019), and Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. v. 10X Genomics, Inc., IPR2019-00566, Paper 21 (PTAB Jul. 22, 2019).

Most practitioners are already familiar with the Becton Dickinson factors, but recent trends show that the scope of discretionary denials under § 325(d) may also be applied to co-pending litigation, as discussed below.

4. Co-pending Litigation

NHK Spring Co. Ltd. v. Intri-Plex Technologies Inc. IPR2018-00752, Paper 8 (PTAB Sep. 12, 2018), is another PTAB decision that was designated as precedential in 2019. In September 2018, the board exercised its discretion in denying institution on an IPR petition under 35 U.S.C. §§ 314(a) and 325(d). NHK Spring had filed for an IPR to challenge the validity of U.S. Patent No. 6,183,841. The board first denied institution under § 325(d) because the cited art had already been considered by the examiner during prosecution. Then the board went on to additionally deny institution under § 314(a), finding that “the advanced state of the district court proceeding is an additional factor that weighs in favor of denying the Petition under § 314(a).” The board reasoned that the petition would not achieve the AIA’s goal of providing an efficient alternative to litigation because a district court proceeding involving the ’841 patent, in which the petitioner also asserted the same prior art and invalidity arguments, would render a decision before an IPR institution decision was issued.

While the NHK Spring decision denied institution based on both §§ 314(a) and 325(d), the PTAB has also exercised discretion to deny institution under only § 314(a), such as in Next Caller Inc. v. Trustid, Inc. In Next Caller, the PTAB denied institution because the “Petition presents substantially the same issues, arguments, and evidence as it has presented in the Parallel District Court Proceeding. The district court has already expended substantial resources to gain familiarity with and resolve these issues, and is set to complete trial in the Parallel District Court Proceeding before any final decision from the Board would be due.” Next Caller, IPR2019-00961, Paper 10 (PTAB Oct. 16, 2019). Accordingly, petitioners will need to consider the new NHK Spring discretionary doctrine as part of their post-grant strategy.

5. The “Reasonable Likelihood” Standard for Multiple Claims and Grounds

Deeper, UAB v. Vexilar, Inc., IPR Case No. 2018-01310, Paper 7 (PTAB Jan. 24, 2019), was designated by the USPTO as an informative decision early in 2019. The PTAB exercised its discretion under § 314(a) to deny the petition because the PTAB concluded that only two of the 23 challenged claims and one of the four grounds had a reasonable likelihood of prevailing on their invalidity challenges. The PTAB explained in its decision that “instituting a trial … directed to only two claims and one ground would not be an efficient use of the Board’s time and resources.” This case seems to signify a post-SAS (SAS Inst., Inc. v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct. 1348, 1354 [2018]) trend in which the PTAB denies institution when only a small number of the total number of claims and grounds in the petition are deemed to have a reasonable likelihood of prevailing. This new doctrine of discretionary denials is in response to the 2018 Supreme Court decision that now prevents the PTAB from partially instituting an IPR proceeding to consider only some of the grounds raised in the petition.

In conclusion, 2019 was a year that continued the PTAB’s trend of denying institution based on the discretion of the judges—a reason unrelated to whether the challenged claims are patentable. Proponents of discretionary denial consider the new doctrines beneficial for reducing the number of patents that are invalidated in post-grant proceedings—a number that they say was too high in the past. Proponents also state that discretionary denials help the PTAB reduce its workload. Opponents of discretionary denial argue that the doctrine allows invalid patents to remain in force even after invalidating prior art has been brought to the PTAB’s attention. Allowing judges to deny institution at their discretion rather than considering the merits leaves open the question of whether the challenged claims are valid—a question that will either need to be decided at a later date or simply left undecided for the life of the patent. Proponents and opponents agree that the PTAB’s use of discretionary denials adds uncertainty to the post-grant process. Petitions based on invalidating prior art are not guaranteed success or even consideration, but rather risk denial if they fail to satisfy the discretionary factors being applied by the PTAB at the time of institution.

In 2020 and beyond, it will be interesting to see whether one or more of the current doctrines of discretionary denial are abandoned by the PTAB (like the once-popular redundancy doctrine of years past) and whether new doctrines are added to the PTAB’s repertoire. Time will tell.

The Role of Estoppel

The contours of estoppel stemming from post-grant trials continued to evolve in 2019. From the petitioner’s perspective, the timing of how and when estoppel arises from 35 U.S.C. § 315(e) continued to evolve.

For example, many district courts in 2019 concluded that the requirement arising from the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS—that the PTAB issue all-or-nothing institution decisions—removes the petitioners’ basis for relying on Shaw Industries Group, Inc. v. Automated Creel Systems, Inc., 817 F.3d 1293 (Fed. Cir. 2016), to escape § 315(b) estoppel. “After SAS, . . . [b]ecause the PTAB must now institute review (if at all) on all grounds, there will be no such thing as a ground raised in the petition as to which review was not instituted. Accordingly, for the words ‘reasonably could have raised’ to have any meaning at all, they must refer to grounds that were not actually in the IPR petition, but reasonably could have been included.” Palomar Technologies, Inc. v. MRSI Systems, LLC, No. 18-10236, slip op. at 14 (D. Mass. Mar. 27, 2019).

Yet most of these cases did not address one increasingly common fact pattern: a petitioner contemporaneously filing multiple petitions against the same patent followed by the PTAB denying a subset of the petitions pursuant to its discretion under § 314(a). See USPTO, TPG Update (July 2019) at 26-28. Where the instituted subset of petitions led to one or more final written decisions, does the estoppel stemming therefrom extend to the grounds articulated in the non-instituted petitions? One recent district court case deals with exactly this issue, and finds that it does not.

Neither Shaw nor SAS specifically addressed the situation here: an IPR petitioner raising grounds in two different petitions, one of which was instituted and one of which was not. While the Supreme Court in SAS held that partial institution was impermissible, the Court did not overrule Shaw’s § 315(e)(2) interpretation—that parties were not estopped from litigating grounds that had previously been presented in an IPR petition but not instituted. See SAS Inst., Inc., 138 S. Ct. at 1353. Nothing in the text of § 315(e)(2) nor the Supreme Court’s holding in SAS expressly requires that an IPR petitioner file only one IPR petition including all its grounds. In fact, IPR petition requirements, such as word limits, discourage raising all possible grounds in a single petition. See 37 C.F.R. 42.24, 42.104. This court thus remains bound by Shaw’s § 315(e)(2) interpretation. Fundamental Innovation Systems International, LLC v. ZTE Corp., No. 3:17-CV-1827, slip op. at 5 (N.D. Tex. Nov. 20, 2019).

This logic may counsel in favor of bringing multiple petitions that include all reasonably viable grounds against a patent, but petitioners need to be careful about the timing of filing those petitions. In SK Hynix Inc. v. Netlist, Inc., the PTAB terminated an IPR only days before the final written decision was due because the panel had recently issued a final written decision against the same patent stemming from another petition filed by the same petitioner only days before the petition in the now-terminated proceeding. See SK Hynix Inc. v. Netlist, Inc., IPR2018-00364, Paper 32 (PTAB Aug. 5, 2019). In that decision, the panel noted, “Petitioner did not seek consolidation of the instant IPR with the [other, completed] IPR, nor did Petitioner seek coordination of the two case schedules.” Id. at 3. Despite the close but not identical schedules, the early delivery of one final written decision precluded a final written decision in the later IPR under 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2). Though this SK Hynix decision is on appeal, petitioners would do well to consider two potential lessons: (1) where possible, file multiple petitions on the same day to ensure close-in-time institution decisions; and (2) request consolidation of proceedings when multiple petitions are instituted.

2019 Biopharma Update

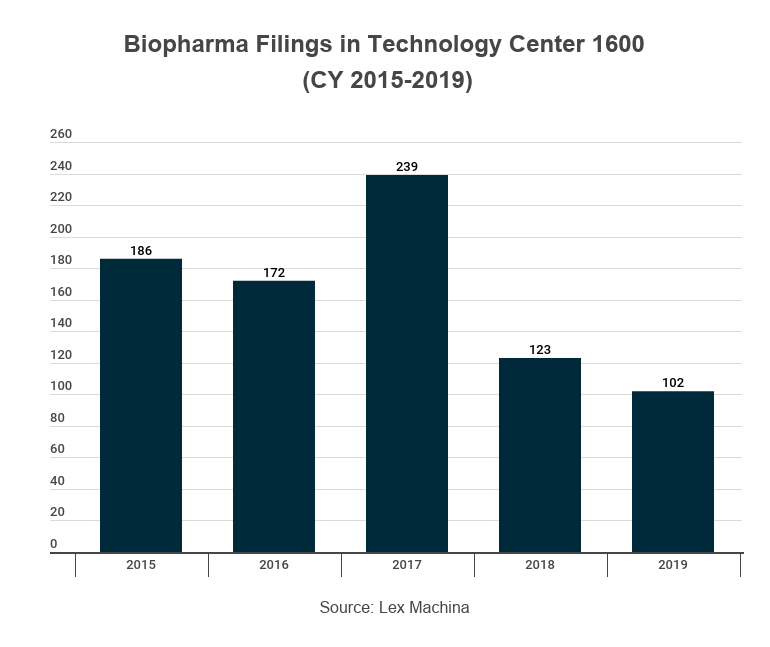

In calendar year (CY) 2019, the total number of post-grant petitions in the biopharma space, which we define as petitions involving Group 1600 patents, was 104 petitions filed, which accounted for 10 percent of all petitions filed. This number was less than the 144 petitions filed in CY 2018 and the record-setting 251 petitions filed in 2017. The vast majority in 2019 were IPR petitions, but 12 PGR petitions were filed. Of the cases that reached an institution decision in the biopharma space, approximately 73 percent were instituted, which is slightly higher than the 68 percent institution rate of 2018 but the same as the 2019 average institution rate of 73 percent across all technology classes. The most active petitioners in 2019 were Nalox-1 Pharmaceuticals, Prollenium, and Abitec Corporation. The most active patent owners in this space were Opiant Pharmaceuticals, Allergan Industries, and Cornell Research.

In 2019, only 12 IPR petitions were filed against patents covering biologic drugs. This number is down from the record-setting 80 biologic petitions filed in 2017 and the 20 petitions filed in 2018. Three of the biologic petitions filed in 2019 challenged patents covering Soliris® (eculizumab), two challenged patents covering Cosentyx® (secukinumab), and the remaining seven were not specific to a marketed product. Of those seven petitions, three are related to methods of purifying proteins and four are related to transgenic mice used for the production of biologics.

Another notable development in the IPR space in 2019 was the revival of the Hatch-Waxman Integrity Act. Then-Sen. Orrin Hatch originally introduced the Hatch-Waxman Integrity Act in June 2018, but the bill was not acted upon during the 115th Congress. In January 2019, Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) and Rep. Bill Flores (R-Texas) reintroduced the Hatch-Waxman Integrity Act (S.344 and H.R.990, respectively) with the goal of foreclosing abbreviated new drug application (ANDA), 505(b)(2), and biosimilar applicants from petitioning for IPR or PGR of patents covering the reference-listed drug or biologic drug. The act proposes to amend the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 U.S.C. § 355(b)(2)) by requiring a 505(b)(2) or an ANDA applicant to certify that it will not institute IPR or PGR of any Orange Book-listed patent and that it will not “rely[] in whole or in part” on any IPR or PGR decision. Similarly, the bill requires biosimilar applicants to certify that they will not seek IPR or PGR of any patent that is known to cover a reference product or a method of its use.

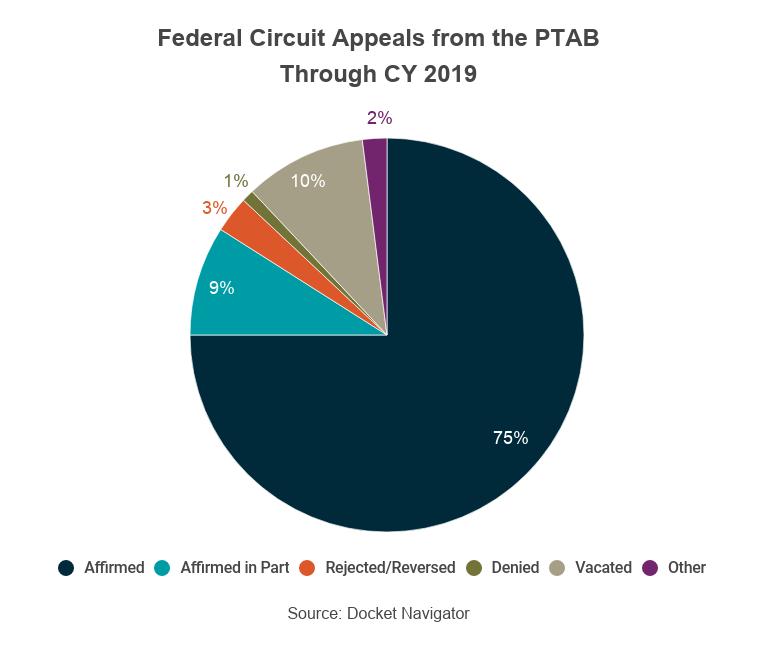

On September 11, 2019, Fish Senior Principal John Dragseth and Associate Nitika Gupta Fiorella hosted the Post-Grant for Practitioners webinar “Post-Grant Appeals: Updates and Reflections.” In it, they discussed the latest post-grant decisions from the Federal Circuit. If you missed the webinar, you can find below a summary of the cases they covered.

Standing

Congress gave any “person” who is not the patent owner standing to bring an IPR, but Article III of the Constitution limits judicial review of an IPR to cases in which there is a true “case or controversy.” That can get in the way of certain IPR petitioners who seek appeal. On the one hand, the court has previously held that a petitioner cannot establish such Article III standing merely by worrying about a patent or by pointing to the fact that it spent money to prosecute an IPR. On the other hand, the court has indicated that a petitioner might not need to allege the sort of infringement threat from a patentee that a declaratory judgment plaintiff would have to establish. Decisions in 2019 help fill in the ground between those end points.

In AVX Corporation v. Presidio Components, Inc., 923 F.3d 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2019), the court considered whether a petitioner-appellant’s status as a competitor of the patent owner-appellee will establish standing. AVX and Presidio were competitors making and selling ceramic capacitors. AVX petitioned for IPR, and the PTAB found some claims patentable and some unpatentable. AVX appealed, but the Federal Circuit found that AVX lacked standing. AVX had relied on the doctrine of competitor standing that has been used in trade and regulatory cases, but the court found that doctrine inapplicable to patent cases because a competitor is not harmed by the mere grant of a potentially relevant patent. Rather, a petitioner must show that it has concrete plans for future activity that creates a substantial risk of future infringement; speculative possible future infringement is not enough to establish injury-in-fact for Article III standing purposes.

Continuing this theme, the court found that potentially infringing future plans (JTEKT Corp. v. GKN Automotive Ltd., 898 F.3d 1217 [Fed. Cir. 2018]) and conclusory assertions of economic harm due to future design-around costs (General Electric Corp. v. United Technologies Corp. [Jul. 10, 2018]) are also not concrete enough to establish standing. However, the court found that standing is present where the appellant had already begun operations that the patentee had stated would implicate the patent. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co. v. Synvina C.V., 904 F.3d 996 (Fed. Cir. 2018). These cases stand for the principle that injury-in-fact in patent cases requires the petitioner-appellant to have already taken steps that could infringe the patent at issue or show concrete plans to do so.

Estoppel

The unforeseen complexity of the AIA estoppel provisions has resulted in numerous appeals to the Federal Circuit—including estoppels against “late” filing of IPRs, estoppels from IPRs into litigations, and estoppels between different IPRs.

Click-to-Call Technologies, L.P. v. Ingenio, Inc., 899 F.3d 1321 (Fed. Cir. 2018), concerned § 315’s one-year time bar to petition for IPR after being served with a complaint. The petitioner-defendant there was sued and served, but the plaintiff voluntarily dismissed the suit without prejudice. When the petitioner-defendant filed an IPR more than a year later, the PTAB treated the suit as if it had never occurred—the dismissal having undone the suit. The Federal Circuit reversed, stating that § 315’s plain language starts the one-year clock ticking when a petitioner-defendant is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent at issue; subsequent dismissal without prejudice does not undo that service. Click-to-Call’s reasoning has since been extended to involuntary dismissals in Bennet Regulator Guards, Inc. v. Atlanta Gas Light Co., 905 F.3d 1311 (Fed. Cir. 2019); to § 315(a)(1) estoppel triggered by the petitioner’s declaratory judgment action in Cisco Systems v. Chrimar Systems, IPR2018-01511 (1/31/19); and to suits where the district court plaintiff lacked standing in GoPro v. 360Heros, IPR2018-01754 (8/23/19). Click-to-Call and its progeny suggest that there is generally no way to undo estoppel once it starts.

In Applications in Internet Time, LLC v. RPX Corp., 897 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2018), the court considered the circumstances under which a party may be considered a privy for estoppel purposes. The appellee, RPX, had a client network whose members would occasionally be sued for patent infringement, and RPX would file post-grant petitions. One of its clients, Salesforce, was sued and RPX filed an IPR petition more than one year later. The patentee argued that RPX’s petition was time-barred under § 315 because RPX was Salesforce’s privy. The question for the Federal Circuit was whether RPX’s interests aligned closely enough with its client’s for the client to be a privy. Without reaching the merits, the court found that the PTAB focused too narrowly on whether Salesforce exercised control over RPX’s IPR filing and that it should have applied a more flexible standard that considers all the available evidence—such as whether a non-party desires review of the patent and whether a petition has been filed at a non-party’s behest.

And in Papst Licensing GmbH v. Samsung Elecs. Am., Inc., 924 F.3d 1243 (Fed. Cir. 2019), the court held that IPR-to-IPR collateral estoppel prevents a party from attacking parts of the board’s obviousness analysis that were common with its analysis in related IPRs where the patentee had appealed from those other IPRs and then voluntarily dismissed its appeals.

Procedure

The Federal Circuit also decided several important cases concerning PTAB policies and procedures.

Ericsson v. Intellectual Ventures I LLC, 901 F.3d 1374 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 27, 2018), concerned what constitutes an improper argument in an IPR reply. The board there had refused to consider, as an improper new argument, an argument related to obviousness made by Ericsson in a reply. The Federal Circuit disagreed, finding that Ericsson’s reply was not an improper new argument because it simply responded to the reasoning of the institution decision and the patent owner’s arguments. All briefing in the case had assumed that the broadest reasonable interpretation standard would apply; only in the patent owner’s response did it argue that Phillips should apply because the patent had expired. Ericsson’s reply pointed to the same disclosures as before in arguing that the prior art and claims as construed under Phillips were insubstantially different, which the court found was not improper because it was responding to matters already in the record and before the board. The opinion emphasizes, however, that this outcome does not change the board’s general authority to decline to address arguments that a reply truly raises for the first time.

In VirnetX, Inc. v. The Mangrove Partners, 2017-1383 (Fed. Cir. Jul. 8, 2019), the court addressed three separate procedural issues but decided only one of them. On joinder, the court declined to decide whether Apple’s joinder under § 315(b)-(c) to an IPR filed by Mangrove Partners was proper where Apple’s original petitions had been time-barred. Because the court found that VirnetX hadn’t demonstrated any prejudice, the court declined to decide the issue. The court also declined to decide whether it had jurisdiction to review the board’s finding that Mangrove Partners identified all real parties in interest because the board did not commit reversible error. Regarding motions for additional discovery, the court found that the board abused its discretion when it denied VirnetX the ability to file a motion for additional discovery even though it planned to deny the motion.

Adidas AG v. Nike, Inc., 894 F.3d 1256 (Fed. Cir. Jul. 2, 2018), considered the limits of the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS, which had held that the PTAB must review every claim a petitioner raised, and here the Federal Circuit extended that holding to cover every ground a petitioner raised.

Sovereign Immunity

In Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe v. Mylan Pharms., Inc., 896 F.3d (Fed. Cir. Jul. 20, 2018), the court considered whether a tribe can claim sovereign immunity as a defense to IPR proceedings. The central question for the court was whether an IPR proceeding is more similar to a federal agency action than to litigation. The court held that because the USPTO director has discretion to institute IPR proceedings, they are more similar to agency actions than to litigation. Therefore, a tribe may not claim sovereign immunity as a defense to IPR. This decision put a stop to patentees assigning patents to tribes.

Constitutionality of IPR for Pre-AIA Patents

Several cases have challenged the constitutionality of IPR proceedings under the Takings Clause, each ending with a determination that the proceedings pass constitutional muster. In Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group, LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365 (2018), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of IPR proceedings as applied to post-AIA patents, but it left open the question of whether the proceedings could constitute unconstitutional takings under the Fifth Amendment when applied to pre-AIA patents. The Federal Circuit answered that question in Celgene Corp. v. Peter, No. 18-1167 (Fed. Cir. 2019), holding that the retroactive application of IPR proceedings to pre-AIA patents is not an unconstitutional taking. In reaching this decision, the court compared AIA post-grant proceedings with pre-AIA post-grant proceedings and found that the differences were not significant enough to suggest a Fifth Amendment taking.

What the Federal Circuit Did in Arthrex

The Federal Circuit reached a different conclusion when evaluating the constitutionality of IPR under the Appointments Clause. In Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc., No. 2018-2140 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 31, 2019) (MOORE Reyna Chen), a three-judge panel held that the IPR statute made PTAB administrative patent judges (APJs) “principal officers” who must, under the Constitution’s Appointments Clause, be nominated by the president with the Senate’s advice and consent. None of those APJs were so appointed. The panel noted that the main factors in determining whether APJs are “principal officers” or instead “inferior officers” who aren’t subject to the Appointments Clause are “(1) whether an appointed official has the power to review and reverse the officers’ decision; (2) the level of supervision and oversight an appointed official has over the officers; and (3) the appointed official’s power to remove the officers.” Slip op. at 9.

In Edmond v. United States, 520 U.S. 651 (1997), the Supreme Court deemed it significant whether an appointed official has the power to review the officer’s decision such that the officer cannot independently render a final decision on behalf of the United States. Applying that standard, the Federal Circuit found that there was no presidentially appointed officer who has the independent statutory authority to review final written decisions of the Board before the decisions issue on behalf of the United States. The Director of the USPTO is the only member of the Board who is nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. However, the Director is only one of more than 200 APJs, and every IPR must be decided by at least three Board judges. As such, the Director lacks the authority to single-handedly review or reverse final written decisions. Absent such review power, the court reasoned, the APJs of the Board function more like principal officers, as they may independently issue final decisions on behalf of the United States.

The extent to which an officer’s work is supervised or overseen by another Executive officer is another factor to consider when determining principal versus inferior officer status. Such supervisory authority can include exercising administrative oversight, prescribing uniform rules of procedure, and overseeing the logistical aspects of the officers’ duties. Here, the court noted several of the Director’s supervisory powers, including the powers to issue policy directives, promulgate regulations governing the conduct of IPR proceedings, provide instructions that include exemplary applications of patent laws to fact patterns, and approve designations of Board decisions as precedential. Finding that these powers enable the Director to exercise “broad policy-direction and supervisory authority over the APJs,” the court held that this factor weighed in favor of a finding that APJs are inferior officers. Slip op. at 13.

Removal power over an officer is a “powerful tool for control” when it is unlimited. Slip op. at 14. The Federal Circuit found that neither the Director of the USPTO nor the Secretary of Commerce has unfettered removal power over APJs. In support of its contention that the Director exercised removal power, the government pointed to the Director’s ability to designate the members of the panel that hears an IPR and to change them at will. However, the court found that the Director’s power to assign certain APJs to certain panels was too limited, falling far short of the power to remove APJs from judicial service without cause. The only actual removal authority the Director or the Secretary of Commerce have over APJs is limited by Title 5, which specifies that APJs may be removed “only for such cause as will promote the efficiency of the service.” Slip op. at 16. Given that APJs are not removable without cause, coupled with the finality of the decisions they issue on behalf of the United States, the court found that this factor weighs in favor of a finding that APJs are principal officers.

Based on the weight of the factors, the panel ultimately determined that APJs are principal officers who must be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. This decision was supported by “[t]he lack of any presidentially appointed officer who can review, vacate, or correct decisions by the APJs combined with the limited removal power,” as well as the court’s finding that the Director does not exercise sufficient control and supervision over APJs to render them inferior officers. Slip op. at 20.

Recognizing that striking the entire IPR regime on this basis would be highly disruptive, the court applied a narrowing remedy it deemed sufficient to establish APJs as legitimate inferior officers. It severed the federal employee protections in 35 U.S.C. § 3(c) so that they do not apply to APJs—i.e., APJs will now serve at the pleasure of the director, with termination at will. In the panel’s view, this severing would remove the Appointments Clause issue and thus preserve the IPR statute’s constitutionality. The panel noted, “It is our view that Congress intended for the [IPR] system to function to review issued patents and that it would have preferred a Board whose members are removable at will rather than no Board at all.” Slip op. at 25.

In the case at bar, the court vacated and remanded the PTAB’s decision without reaching the merits, as it found that it was made by a panel of unconstitutionally appointed APJs. Relying on Lucia v. S.E.C., 138 S. Ct. 2044 (2018), the court held that the only way to cure the constitutional defect was to designate a new panel of APJs to hear the case, as “the remedy [cannot be] to vacate and remand for the same Board judges to rubber-stamp their earlier unconstitutionally rendered decision.” Slip op. at 30.

The court also quickly issued several orders that relied on Arthrex. On the same day as Arthrex, the court sua sponte remanded Uniloc 2017 LLC v. Facebook, Inc., __ F.3d __, Docket 2018-2251 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 31, 2019) (Non-Precedential Order), because the appellant there had made an Appointments Clause challenge in its opening (blue) brief. And the next day, in two precedential orders, the court found Appointments Clause challenges waived where they were not raised in the appellant’s opening briefs and were raised for the first time after Arthrex. See Customedia Technologies, LLC v. Dish Network Corp., __ F.3d __, Docket 2018-2239 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 1, 2019) (Precedential Order) (treating a Rule 28(j) citation of supplemental authority as a motion and denying that implied motion) and Customedia Technologies, LLC v. Dish Network Corp., __ F.3d __, Docket 2019-1001 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 1, 2019) (Precedential Order) (denying an express motion).

What Happens Now?

As of the date of publication, all three parties to the case—Arthrex, Inc., Smith & Nephew, Inc., and the federal government—have filed petitions for rehearing and/or rehearing en banc, meaning that the ultimate resolution could be a year or more into the future. Our observations made here are thus preliminary, and much will change as the bar absorbs the opinion and as the Federal Circuit, the USPTO, and other parties react to it.

Nonetheless, we should expect the USPTO and the Federal Circuit to work to prevent cases from stacking up in one place, such that a large number would have to be handled at one time in the future. We’ve already seen some such effort in the quick orders in the Customedia appeals. Another area of docketing concern will be appeals that do raise the issue going forward and then stack up in the Supreme Court’s queue, waiting for some decision on this issue. When the Supreme Court acts, those cases could head back down en masse for reworking at the PTAB or consideration on the merits at the Federal Circuit.

Specific to the PTAB’s docket, the Arthrex panel noted that the case had to go to a new group of APJs, but that the PTAB could decide how much work needs to be repeated. The panel also noted that “the decision to institute is not suspect.” Slip op. at 30. Readers should not necessarily extrapolate that statement to their particular case, as the reviewability of institution decisions is a very complex issue. In any event, Arthrex’s remand instructions leave open the possibility that IPRs will involve study by a new panel and a new final written decision but will not involve extra submissions from the parties.

Because any review of this decision will take time (at least a couple of months) and IPRs need to keep rolling along, the director likely will want to minimize the number of cases that could be affected by this ruling. There are certainly complexities of switching APJs to “at will” employees, so it is hard to predict exactly how fast the USPTO can act and how it will act. It might be possible to make APJs proper “inferior officers” without depriving them of the civil service protections other federal employees enjoy. One option would be new regulations giving the director more authority over the content of IPR decisions. However, it is unclear how much flexibility he has in this regard, since he already suggested a number of such options to the Federal Circuit in connection with this appeal, which the Arthrex panel rejected. It is also unclear whether the director could, by regulation, restore APJs’ judicially severed employment protections even if he does come up with an alternative fix to the problem. He certainly also must be considering a more long-term legislative fix.

The director may also take action like he did after the Supreme Court, in SAS, found partial institution to be a problem. There, the USPTO began quickly asking parties in ongoing IPRs to state whether they were willing to move forward without objecting to pending problems in their IPRs. Here, the Director might “fix” the APJ problem and then ask all parties in ongoing IPRs whether they object to any prior actions by their panels (e.g., institution, discovery, or evidentiary rulings). Because institution decisions are unreviewable at least to some extent, because PTAB panels often make no permanent rulings until the final written decision, and because parties who don’t complain in response to a communication from the director might be deemed to have waived their complaints, the director could greatly reduce the amount of “cleanup” needed for pending IPRs, as he did after SAS.

It also remains unclear whether the severability remedy the Federal Circuit adopted and its decision to order remands are constitutional. In Bedgear, LLC v. Fredman Bros. Furniture Co., Inc., No 18-2082 (Fed. Cir. 2019), Judge Dyk, joined by Judge Newman, wrote in a concurrence that the remedy aspect of Arthrex (requiring a new hearing before a new panel) is not required by Lucia, imposes large and unnecessary burdens on the IPR system, and involves unconstitutional prospective decision-making. According to Judge Dyk, the court in Arthrex should have severed Title 5 protections from APJs both retroactively and prospectively so as to render all decisions of the PTAB constitutional. This is based on the principle that administrative agencies (such as the SEC in Lucia) and legislatures generally act only prospectively, whereas judicial constructions of statutes are necessarily retroactive as well as prospective. The Supreme Court has recognized a general rule of retroactive effect for constitutional decisions in several cases. See, e.g., Harper v. Virginia Dep’t of Taxation, 509 U.S. 86 (1993); Reynoldsville Casket Co. v. Hyde, 514 U.S. 749 (1995). In cases involving Appointments Clause challenges, the Supreme Court has required a new hearing only where the appointment’s defect had not been cured or where the cure was the result of nonjudicial action. As neither was true of Arthrex, in Judge Dyk’s view the decision was inconsistent with Supreme Court precedent and creates uncertainty about the point in time when the appointments became valid. Ultimately, the Supreme Court may have to weigh in.

Supreme Court Decisions

In Return Mail v. United States Postal Service, the Supreme Court elucidated the standing issue as to whether the government is a “person” for the purposes of post-issuance proceedings under the AIA. 587 U.S. __ (2019) (Slip op. at 1). For context, Return Mail sued the United States Postal Service (USPS) in the Court of Federal Claims for patent infringement; in addition to asserting invalidity as a defense, the USPS petitioned for covered business method (CBM) review. Slip op., 5. After the CBM review canceled all patent claims, Return Mail appealed that the USPS lacks standing because it is not a “person” eligible to petition for CBM review. Id. A divided Federal Circuit panel affirmed the PTAB’s decision, finding that the structure of the Patent Act and the policies underlying the AIA suggested that the term “person” includes federal agencies. 868 F.3d 1350, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2019). Judge Newman dissented, finding that long-standing precedents, the federal Dictionary Act, and the interplay between the benefit of AIA proceedings and the estoppel arising from such proceedings (but which would not apply against the government in the Court of Federal Claims) meant that federal agencies are not “persons” eligible for AIA post-issuance proceedings. Id. at 1367.

In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court reversed and held that federal agencies cannot avail themselves of AIA post-issuance proceedings because the government is not a “person” for the purposes of AIA post-issuance proceedings. Slip op., 17-18. The majority (as well as Judge Newman) started from the presumption that the government is a sovereign, not a “person.” Slip op., 6-9. This presumption is evident in a long pedigree of Supreme Court cases, thus reflecting the “common usage” and the express directive from Congress in the Dictionary Act regarding the general statutory definition of “person.” Id. The majority found that the USPS failed to rebut the presumption because (1) other references to “person” in the AIA itself do not consistently include the government (slip op., 9-12), (2) congressional authorization for the government to initiate “a hands-off ex parte reexamination” does not imply an open ticket to “a full-blown adversarial proceeding before the Patent Office and any subsequent appeal” (slip op., 13-15), and (3) excluding federal agencies from the AIA review proceedings does not unfairly prejudice the government, which, unlike a private entity, can defend patent infringement in the Court of Federal Claims under § 271(e)(4) where none of injunction, jury trial, and punitive damages are available (slip op., 15-17).

The dissent asserted (1) the references to “person” that included federal agencies were more analogous to the use in relation to AIA review than other references to “person” that excluded federal agencies (slip op. 23-25), (2) congressional mandates to “improve the quality of patents” and “make the patent system more efficient” by providing an easier way for parties to challenge “questionable patents” do not differentiate whether the government or a private party is the accused infringer (slip op., 26-27), and (3) infringement suits can threaten to injure government interests even absent the specter of injunctive relief (slip op., 27-29).

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.