IP Law Essentials

How Biosimilars Are Approved and Litigated: Patent Dance Timeline

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

A biosimilar is a biological product that is highly similar to and has no clinically meaningful differences from an FDA-approved reference biological product. Biosimilar applicants have a number of choices to make on the path to a commercial biosimilar product. To start, the biosimilar applicant can either launch at risk or try to clear the patent rights controlled by the reference product sponsor ("RPS") before launch. If a biosimilar applicant chooses to clear the RPS's patent rights, it may (or may not) engage in a procedure called the "patent dance" and optionally participate in multiple waves of litigation, as set forth in the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act ("BPCIA"). This blog outlines the path to biosimilar approval and launch and explains some of the decisions that a biosimilar applicant must make along the way.

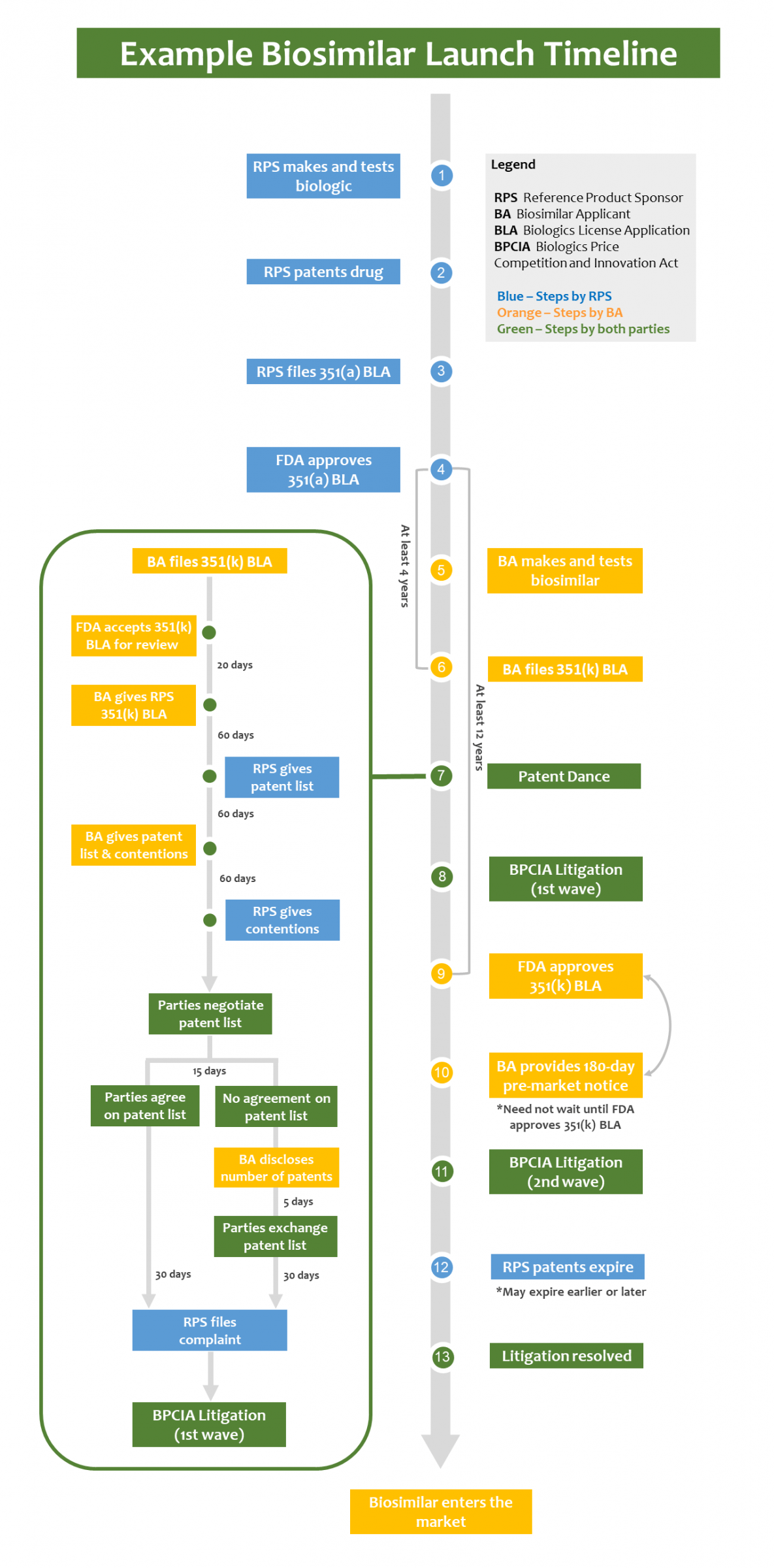

The discussion here focuses on one possible scenario (illustrated in the timeline below) in which a biosimilar applicant chooses to engage in the patent dance. In this example, the biosimilar applicant leaves patents on the table for a second wave of litigation. Each step of the timeline is explained in more detail below.

Steps 1-4: Reference Product is Approved and Patented

Just as a generic drug undergoes an abbreviated regulatory review process that references an approved "brand-name" drug, a biosimilar undergoes an abbreviated regulatory review process that references an approved "reference product" or "reference biological drug." The discussion of a biosimilar's lifecycle necessarily starts with the reference product what happens during the approval and patenting process of a reference product impacts how and when a biosimilar is launched.

Step 1. A Reference Product Sponsor Makes and Tests a Biological Drug

Biologics are a diverse category of pharmaceutical products that are often produced or isolated from living sources, such as cells. When developing a biological drug, the RPS must perform clinical trials to show the drug is safe and effective.

Step 2. The Reference Product Sponsor Patents the Biological Drug

An RPS may seek patents directed to the biological drug, including patents covering drug composition, methods of manufacturing the drug, and methods of using the drug for treatment. Patents do not give the RPS an affirmative right to practice the patented invention, but do give the RPS the right to exclude others from making, selling, and offering to sell an infringing biosimilar in the United States even if the FDA has approved the biosimilar.

Step 3. The Reference Product Sponsor Files a Section 351(a) Biologics License Application with the FDA

An RPS submits a Section 351(a)[1] Biologics License Application ("BLA") to obtain FDA approval of its biological drug. 42 U.S.C. 262(a). The RPS must submit to the FDA clinical and non-clinical study information showing that the drug is safe, pure, and potent. 21 C.F.R. 601.2.

Step 4. The FDA Approves the Biological Drug

When the FDA approves a biological drug, it triggers an exclusivity period for that drug. Under the BPCIA, new biological drugs currently enjoy at least 12 years of market exclusivity. Until this exclusivity period expires, the FDA may not approve an application for a biosimilar version of that drug. 42 U.S.C. 262(k)(7)(A). In addition, a biosimilar applicant may not submit a Section 351(k) BLA until 4 years after the FDA approves the reference biological drug. Id. 262(k)(7)(B).

Steps 5-6: A Biosimilar is Developed and Submitted to the FDA

Step 5. The Biosimilar Applicant Makes and Tests a Biosimilar

A potential biosimilar applicant may begin making and testing a biosimilar drug even before a reference product's exclusivity period expires.

Can the RPS sue a potential biosimilar applicant for developing a biosimilar? Generally no. The Patent Statute includes a safe harbor provision that protects a potential biosimilar applicant engaged in drug development activity from being sued for patent infringement, as long as the potential biosimilar applicant is performing otherwise infringing activities "solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information" to the FDA. 35 U.S.C. 271(e)(1). However, certain pre-launch activities, such as stockpiling commercial inventory, might not be protected by the safe harbor provision. See Amgen Inc. v. Hospira, Inc., 944 F.3d 1327, 1339-40 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

Step 6. The Biosimilar Applicant Files a Section 351(k) Biologics License Application with the FDA

Under the BPCIA, a biosimilar applicant may rely on the reference product's safety and efficacy data to seek biosimilar approval with the FDA. Specifically, a biosimilar applicant submits a Section 351(k) BLA to seek FDA approval of its biosimilar drug. 42 U.S.C. 262(k). The biosimilar applicant may file a Section 351(k) BLA four years (or more) after the FDA approves the reference product. Id. 262(k)(7)(B).

Under the BPCIA, the biosimilar applicant must show that its product is highly similar to, and has no clinically meaningful differences from, the FDA-approved reference product. Id. 262(i)(2); see id. 262(k)(2)(A)(i)(I). The applicant need not submit the same safety and efficacy data found in a Section 351(a) BLA instead, the biosimilar applicant submits data such as biosimilarity studies, toxicity studies, and condition of use studies. Id. 262(k)(2)(A)(i)(I). In addition, the biosimilar applicant must show:

- that its product "utilize[s] the same mechanism or mechanisms of action for the condition or conditions of use prescribed, recommended, or suggested in the proposed labeling, but only to the extent the mechanism or mechanisms of action are known for thereference product";

- that "the condition or conditions of use prescribed, recommended, or suggested in the labeling proposed for the[biosimilar] have been previously approved for thereference product";

- that "the route of administration, the dosage form, and the strength of the[biosimilar] are the same as those of thereference product"; and

- that "the facility in which the[biosimilar] is manufactured, processed, packed, or held meets standards designed to assure that the[biosimilar] continues to be safe, pure, and potent."

Id. 262(k)(2)(A)(i)(II)-(V).

The biosimilar applicant may also apply for interchangeable status by showing that its product is "expected to produce the same clinical result as [its] reference product in any given patient," and if the product will be administered more than once, it will not increase safety risks or decrease efficacy if it is switched with the reference product. Id. 262(k)(4).

Steps 7-8: First Wave of Litigation

If a biosimilar applicant wants to launch a biosimilar while the RPS's patents covering the biologic drug are still in force, it may do so at risk or choose to clear the RPS's patent rights. If the biosimilar applicant chooses to clear the RPS's patent rights, it may engage in the "patent dance."

Step 7. Once the FDA Accepts the Biosimilar Applicant's Section 351(k) BLA, the Biosimilar Applicant May Initiate the Patent Dance

The BPCIA envisions two potential waves of biosimilar litigation. The first wave is triggered when the biosimilar applicant submits a Section 351(k) BLA to the FDA. Submitting a Section 351(k) BLA, like submitting an application to market a generic small molecule drug (referred to as an Abbreviated New Drug Application, or "ANDA"), is an "artificial act of infringement." 35 U.S.C. 271(e)(2)(C). The RPS is not allowed to sue right at this moment, however. It must wait and see whether the biosimilar applicant initiates a procedure commonly called the "patent dance."

The patent dance is a pre-suit exchange between the biosimilar applicant and the RPS to identify and potentially narrow the list of patents litigated in the first wave of litigation. Only the biosimilar applicant can decide whether to dance.[2]

If the biosimilar applicant chooses to start the patent dance, it must send a copy of its Section 351(k) BLA to the RPS within 20 days after the FDA accepts it. 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(2). The RPS then has 60 days to provide a list of patents it wants to assert and identify which patents on that list the RPS would be prepared to license to the biosimilar applicant. Id. 262(l)(3)(A). Next, the biosimilar applicant has 60 days to provide a list of other patents it believes should be included in litigation (if any) and respond to the RPS's license offer. Id. 262(l)(3)(B)(i); id. 262(l)(3)(B)(iii). The biosimilar applicant must also provide either detailed statements with factual and legal bases for invalidity, unenforceability, or non-infringement, or a statement that it does not intend to market its biosimilar before the RPS's patents expire. Id. 262(l)(3)(B)(ii). If the biosimilar applicant provides a detailed statement, the RPS has 60 days to respond with its own detailed statements on validity, enforceability, and infringement. Id. 262(l)(3)(C).

After these exchanges, the parties negotiate the final patent list to be litigated in the first wave of litigation. Id. 262(l)(4)-(6). If the parties agree on a final patent list within 15 days, the RPS has 30 days to file a patent infringement complaint directed to those patents. Id. 262(l)(4); id. 262(l)(6)(A). If the parties do not agree on a final patent list within 15 days, the parties exchange another set of patent lists. This time, the biosimilar applicant first discloses how many patents it will list, and the parties simultaneously exchange patent lists within 5 days after the disclosure. Id. 262(l)(5)(A); id. 262(l)(5)(B)(i). The RPS may not list more patents than the biosimilar applicant (unless the biosimilar applicant lists zero patents, then the RPS may list one). Id. 262(l)(5)(B)(ii). The RPS then has 30 days to file a patent infringement complaint asserting the patents listed by both parties. Id. 262(l)(6)(B). If the RPS does not file a complaint within 30 days, it faces certain ramifications such as limiting its damages recovery to only a reasonable royalty. 35 U.S.C. 271(e)(6)(B).

Step 8. First-Wave Litigation Depends on the Patent Dance

If the biosimilar applicant initiated the patent dance by providing its Section 351(k) BLA to the RPS within 20 days of FDA acceptance, the RPS may bring a patent infringement suit on the negotiated patents within 30 days after the patent dance concludes. 35 U.S.C. 271(e)(2)(C)(i); 42 U.S.C. 262(l). This first-wave litigation is like traditional patent litigation, except both parties have already exchanged detailed statements addressing infringement, validity, and enforceability. In contrast, in traditional patent litigation, no contentions are exchanged until after a patentee has filed its complaint and the alleged infringer has answered. In patent litigation related to a generic small molecule drug under the Hatch-Waxman Act, the generic manufacturer provides some pre-litigation positions in the form of a "paragraph IV certification," but the "brand-name" company does not.

If the biosimilar applicant initiated the patent dance, neither party may bring a declaratory judgment action[3] on Section 262(l)(3) patents that were not included in first-wave litigation until the biosimilar applicant provides 180-day notice of commercial marketing. Id. 262(l)(9)(A).

If, after initiating the patent dance, the biosimilar applicant skips parts of the dance, the biosimilar applicant may face ramifications. For example, the RPS, but not the biosimilar applicant, may bring a declaratory judgment action of infringement, validity, and enforceability on Section 262(l)(3)(A) patents if the biosimilar applicant "fail[ed] to complete an action" required by Section 3(B)(ii), Section 5, Section (6)(C)(i), Section 7, or Section (8)(A). 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(9)(B).

So far, biosimilar applicants have not been able to jump-start patent litigation by filing a declaratory judgment action before the FDA accepts the biosimilar applicant's BLA or mid-way through the patent dance.

Steps 9-11: Second Wave of Litigation

Step 9. The FDA Approves the Biosimilar Product

If the reference product's market exclusivity has expired, and the biosimilar product meets the BPCIA's and the FDA's requirements, the FDA may approve the biosimilar product. 42 U.S.C. 262(k). This means the FDA gives permission to sell the drug in the United States. Id. 262(a)(1).

Step 10. Biosimilar Applicant Provides 180-Day Notice of Commercial Marketing

At least 180 days before the biosimilar is first marketed, the biosimilar applicant must give notice to the RPS. 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(8)(A). The biosimilar applicant does not need to wait until the FDA approves the biosimilar before providing notice; it might provide notice far in advance so that it can launch the biosimilar as soon as the biosimilar applicant obtains FDA approval. See Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1664, 1677 (2017).

Step 11. Second-Wave Litigation May Commence

As soon as the RPS receives the 180-day Notice of Commercial Marketing, it can begin the second wave of BPCIA litigation and seek a preliminary injunction prohibiting the manufacture or sale of the biosimilar. During the second wave of litigation, the RPS can assert any patent from the original Section 262(l)(3) patent lists (initially exchanged by the parties during the patent dance) that was not included in the first wave of litigation. 42 U.S.C. 262(l)(8)(B). If the RPS does not bring a preliminary injunction action, or if the court refuses to grant a preliminary injunction, the biosimilar can be launched while litigation proceeds. Note that both parties can bring declaratory judgment actions during second-wave litigation. Id. 262(l)(9)(A); Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1664, 1672 (2017).

Steps 12-13: Resolution

Step 12. The Reference Product Sponsor's Patents Expire

The RPS's patents may expire before or after litigation is resolved. Even if a biosimilar applicant waits to launch until patent expiration, recent case law suggests it may still be liable for pre-launch infringing activities performed while the patents were still in force (e.g., making and stockpiling commercial batches for future commercial sale). See Amgen Inc. v. Hospira, Inc., 944 F.3d 1327, 1339-40 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

Step 13. Both Waves of Litigation are Resolved

Once the two waves of BPCIA litigation are resolved, the biosimilar applicant will know whether it can launch its biosimilar (or keep a biosimilar launched at risk on the market). Settlement agreements may dictate when a biosimilar may enter the market. For example, some biosimilar companies have settled with AbbVie to delay Humira® biosimilar launch in the United States until 2023. Even after entering the market, whether biosimilars will be able to effectively compete against reference products remains an open question.

More questions? Contact the authors or visitFish's Intellectual Property Law Essentials.

[1] Sections 351(a) and 351(k) refer to Section 351 of the Public Health Service Act, as amended by the BPCIA, which is codified at 42 U.S.C. 262.

[2] Courts have held that a biosimilar applicant cannot be forced to engage in the patent dance by an injunction under state or federal law. Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1664 (2017); Amgen Inc. v. Sandoz Inc., 877 F.3d 1315, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The discussion here is limited to the scenario where a biosimilar applicant participates in the patent dance.

[3] Generally, in a declaratory judgment patent action, a party threatened with the possibility of a lawsuit preemptively sues another party, asking the court to decide issues of patent infringement or validity.

Authors: Cheryl Wang, Nicole Williams, Kayleigh McGlynn, Grant Rice, Jenny Shmuel

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.