Post-Grant Report

2020 Post-Grant Annual Report

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Senior Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

IN A YEAR OF EXTRAORDINARY CHANGE, THE PATENT TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD (PTAB) ROSE TO THE CHALLENGE

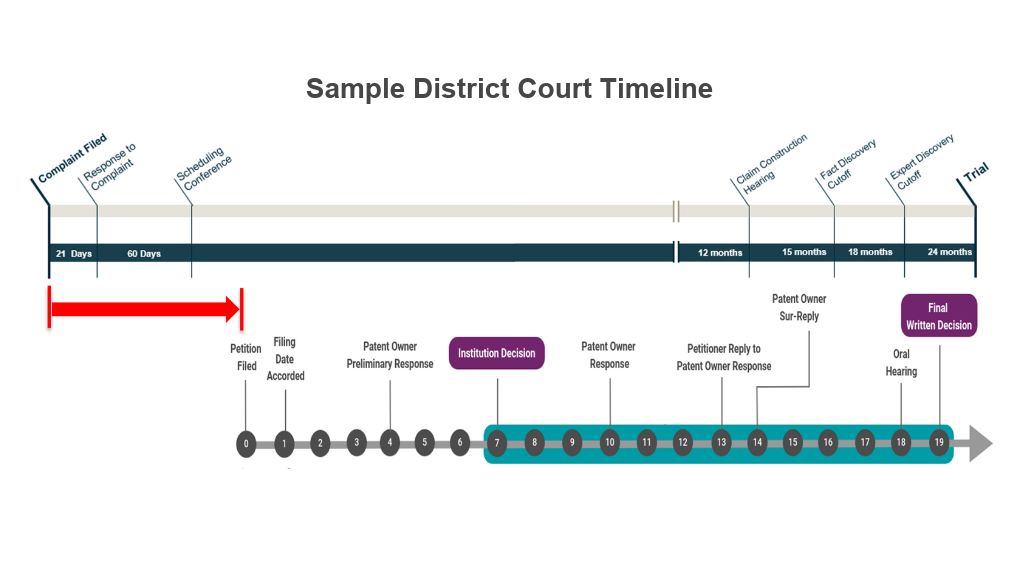

Given the challenges of 2020 – a global pandemic, a deep economic recession, and a turbulent presidential election, among others – a slowdown in activity at the PTAB would not be unexpected. But a comparison of 2019 and 2020 statistics reveals that filings actually increased by about 15%,¹ reversing a decline of about 30% between 2018 and 2019. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) attributes this success to a two-year IT stabilization and modernization effort, which allowed the agency to transition 13,000 employees to remote work relatively seamlessly. The PTAB also became one of the first tribunals in the country to conduct virtual hearings, having held over 1,000 all-virtual hearings by year’s end.²

It was otherwise a fairly quiet year for post-grant practice at the PTAB. The PTAB Precedential Opinion Panel issued just one decision (Hunting Titan, Inc. v. DynaEnergetics Europe GMBH, IPR2018-00600), down from three in 2019. In December, the USPTO issued two final rules: the first implementing the SAS rules of institution and eliminating the presumption at institution in favor of the petitioner as to testimonial evidence, and the second allocating the burden of persuasion in motions to amend. It also issued a notice of proposed rulemaking in October concerning its proposed rule to codify its current policies and procedures regarding the PTAB’s discretion to institute AIA trials. And on September 16, the number of AIA trial proceedings available to petitioners shrunk to two with the sunsetting of the Covered Business Method (CBM) Review program. Looking forward, all eyes are on the Supreme Court as it prepares to decide the constitutionality of the appointment of PTAB judges in Arthrex.

Fish & Richardson’s 2020 Post-Grant Report takes a deep dive into the most important cases, trends, and developments that have shaped post-grant practice over the previous year and how they may affect practitioners going forward.

When it comes to post-grant practice, Fish’s history and presence are unmatched: We have handled more cases at the PTAB than any other firm, our attorneys routinely craft new law at the Federal Circuit, and we host the most innovative educational programs. For more information, please contact practice group chairs Dorothy Whelan or Karl Renner, or visit fishpostgrant.com.

For even more 2020 post-grant updates, please see our Post-Grant 2020 Year in Review webinar here.

The Board formally announced its new pilot program for motions to amend on March 15, 2019. Fed. Reg. 9497 (Mar. 15, 2019). The pilot program allows the patent owner to seek non-binding preliminary guidance from the Board evaluating its proposed claims against the petitioner’s challenges. The patent owner then has four options: (1) file a revised motion to amend; (2) file a reply to the petitioner’s opposition; (3) allow the petitioner to reply and receive the last word in a patent owner’s sur-reply; or (4) withdraw the motion to amend. These options put the patent owner in control of the proceeding. Yet, more than a year into the pilot program, the jury is still out on whether the program has had the desired effect of “enhanc[ing] the effectiveness and fairness of AIA trial proceedings.” Fed. Reg. 54319, 54322 (Oct. 29, 2018).

Evaluating “effectiveness and fairness” is no easy task. But one measure that might shed light on these issues is the rate at which patent owners have used the new motion to amend procedures compared to the prior regime. If nothing else, filing rate trends can be relevant to the perception of effectiveness and fairness. At this point, based on the PTAB’s published statistics and open data, there is no sign of an increased motion-to-amend filing rate.

Filing rates, while relevant, are inconclusive. Apart from the “effectiveness and fairness” of the PTAB’s procedures, several reasons may be steering patent owners away from pursuing claim amendments at the PTAB. For example, patent owners can obtain amendments in ex parte reexamination, reissue, and open prosecution without active resistance from a motivated adverse party. These alternatives also can be considerably cheaper, more predictable, and have higher success rates — not to mention that reissue and open prosecution may offer opportunities for non-narrowing amendments, unlike amendments at the PTAB.

Looking forward, success rates tend to provide a leading indicator, and here, the early results shed a more favorable light on the pilot program. Per the PTAB’s published statistics, only about 14% of pre-pilot program motions to amend were at least partially granted.¹ By contrast, Director Iancu recently reported a 36% rate of at least partially granted motions when patent owners utilized the pilot program.² There is no question that patent owners, thus far, have found more success under the Board’s new procedures than the old.

The table below provides a breakdown of the patent owners’ strategic choices in 11 pilot program cases with positive outcomes:

| Option 1: Revised Motion to Amend | 5 |

| Option 2: Reply (no revised motion) | 5 |

| Option 3: Sur-Reply (no revised motion) | 1 |

Small sample size issues aside, one interesting observation is that several of these positive outcome cases did not involve a revised motion to amend, currently the most popular strategic choice among patent owners. And of the subset that opted against filing a revised motion, only a few received fully positive guidance. In each of the remaining cases, the patent owner decided to address the negative preliminary guidance head-on with argument and evidence, rather than new claim language.

The choice to forego a revised motion to amend in response to negative preliminary guidance may seem counterintuitive initially, but less so when considered in context. The pilot program structure is such that the Board’s guidance comes before the patent owner can respond to the petitioner’s opposition. It makes sense, then, that the guidance is negative in the overwhelming majority of cases. The consequences of filing a revised motion to amend provide another critical piece of context. On the filing of a revised motion, the record is fully open to new grounds of challenge from the petitioner, and the patent owner is flying blind as to the Board’s assessment of any new claim language. A revised motion is undoubtedly helpful in the right circumstances, but it is not the only viable choice.

Apart from withdrawing the motion altogether, each of the three options presented to a patent owner following the Board’s preliminary guidance can be effective. Early results suggest that patent owners, while still facing an uphill climb, now have better odds of obtaining amended claims. It remains to be seen whether the increased chances of success will tempt more patent owners to try their hand at motions to amend.

The Latest in Discretionary Denials

2020 was an interesting year for discretionary denial under 35 U.S.C. § 314(a). In May, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) designated, as precedential, a decision addressing considerations applicable to the PTAB’s use of discretion to deny institution in view of parallel litigation of the challenged patent. Apple Inc. v. Fintiv, Inc., IPR2020-00019, Paper 11 (PTAB Mar. 20, 2020). The Fintiv decision laid out a six-factor test used to assess a parallel, co-pending proceeding:

- whether the court granted a stay or evidence exists that one may be granted if a proceeding is instituted;

- proximity of the court’s trial date to the Board’s projected statutory deadline for a Final Written Decision;

- investment in the parallel proceeding by the court and the parties;

- overlap between issues raised in the petition and in the parallel proceeding;

- whether the petitioner and the defendant in the parallel proceeding are the same party; and

- other circumstances that impact the Board’s exercise of discretion, including the merits.

The Board explained that “[t]hese factors relate to whether efficiency, fairness, and the merits support the exercise of authority to deny institution in view of an earlier trial date in the parallel proceeding.” Id. at 6. The Board recognized that “there is some overlap among these factors” and evaluates the factors by taking “a holistic view of whether efficiency and integrity of the system are best served by denying or instituting review.” Id.

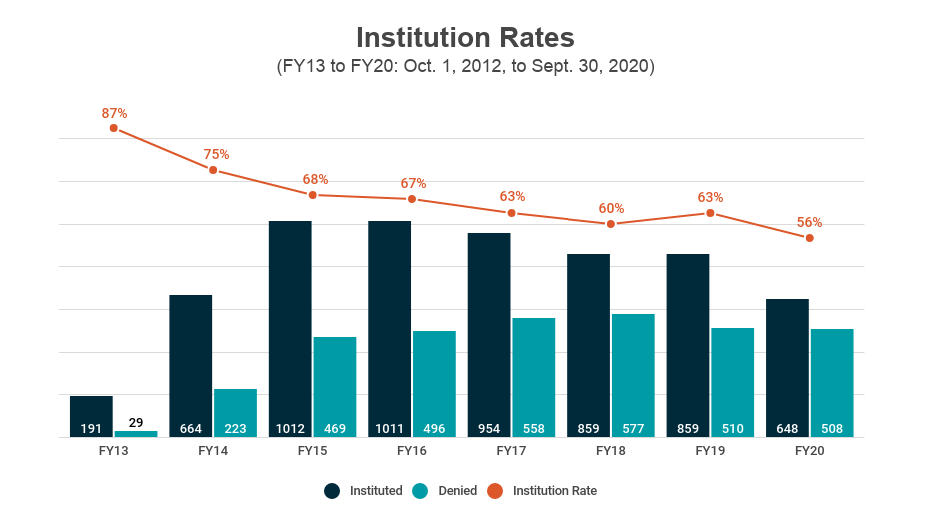

With the adoption of the Fintiv test as precedential, the PTAB reinforced the use of discretion to deny otherwise timely and meritorious petitions based on the stage of a parallel proceeding. This reinforcement has increased the number of patent owners seeking to gain denial of institution in view of a fast schedule in parallel litigation. In 2020, there appears to be a statistical difference, some of which can be attributed to the rise of discretionary denials:

Indeed, in jurisdictions with expeditious trial schedules, such as the Eastern and Western Districts of Texas and the International Trade Commission (“ITC”), the Fintiv factors may often lean in favor of institution denial (depending upon the promptness of the petitioner’s challenge at the PTAB). For example, if a defendant files an IPR petition ten months after the complaint was served in these forums (which is safely within the “one year” bar set by Congress in 35 U.S.C. § 315), such a defendant may have little chance of demonstrating that factors one, two, or five weigh in favor of institution. Of course, if a defendant files its IPR petition shortly after the litigation complaint is served, this increases the likelihood that the projected date of the Board’s Final Written Decision will occur before the scheduled date of the jury trial:

Factor three also is impacted by fast-moving litigation, although its impact can be mitigated by filing petitions promptly after the litigation has commenced. Moving quickly to file petitions, however, creates its own perils for petitioners because it requires moving forward with limited information about infringement allegations and requires early formulation of case strategy to ensure consistency between forums.

With this in mind, emphasis often is placed on factor four, and petitioners have taken measures to assuage concerns relating to prospective overlap of issues raised in petitions and issues to be resolved in parallel civil proceedings involving the same patent. For example, petitioners have attempted to differentiate the prior art being advanced at the PTAB from the prior art at issue in the parallel litigation. In some cases, petitioners have used prior art at the PTAB that was not advanced in the parallel proceeding. In other cases, petitioners have offered stipulations to avoid overlap. In them, petitioners agree not to advance certain prior art in the parallel proceeding. These stipulations have taken various forms. Some petitioners have opted for unconditional stipulations, but most have used conditional stipulations that are conditioned on the PTAB granting institution before the stipulation becomes effective. The scope also has varied with petitioners limiting stipulations to (1) only the specific grounds advanced in the petition, (2) only the primary references advanced in the petition, (3) all prior art advanced in the petition, or (4) all 102 and 103 defenses based on printed publication prior art.

On December 17, 2020, the PTAB addressed stipulations by designating precedential a decision where petitioner filed a broad stipulation to limit grounds in district court. Sotera Wireless, Inc. v. Masimo Corporation, IPR2020-01019, Paper 12 (Dec. 1, 2020). In Sotera, the Board endorsed “a stipulation that, if IPR is instituted, [petitioner] will not pursue in the District Court Litigation any ground raised or that could have been reasonably raised in an IPR.” Id. at 18 (emphasis added). The Board explained that “Petitioner’s stipulation here mitigates any concerns of duplicative efforts between the district court and the Board, as well as concerns of potentially conflicting decisions.” Id. at 19. Based on Sotera, if petitioners are willing to impose a “self-estoppel” at the time of institution similar to the estoppel provisions of 35 U.S.C. § 315 that normally take effect only at the time of a Final Written Decision, the Board is far less likely to invoke discretionary denial based on the Fintiv precedent.

Petitioners challenging more claims at the PTAB than involved in co-pending litigation have also noted the consequential absence of overlap in issues that will be addressed in parallel civil actions. Patent owners have countered by stipulating, contingent upon denial of institution, that they will limit assertion of the patent against the petitioner to those claims involved in the parallel proceeding. See SK Innovation Co., Ltd. v. LG Chem, Ltd., IPR2020-01036, Paper 13 (Nov. 30, 2020).

The merits also have occasionally played a relatively large role in the PTAB’s exercise of discretion under Fintiv’s factor six. For example, the PTAB has found “a strong showing on the merits” sufficient for factor six to weigh strongly against discretionary denial and outweigh a finding that factors two, three, and five weigh in favor of exercising discretion. See, e.g., Apple Inc. v. Seven Networks, LLC, IPR2020-00255, Paper 13, (July 28, 2020).

Further, the PTAB has expanded the Fintiv inquiry beyond district court cases, applying the same analysis to investigations by the ITC. Although the ITC, unlike a district court, has no power to enter a final judgment regarding patent validity that would have issue-preclusive effect on the parties, recent decisions have held that an early ITC determination bars PTAB review under Fintiv. See, e.g., Garmin Int’l, Inc. v. Koninklijke Philips N.V., IPR2020-00754, Paper 11 (Oct. 27, 2020).

With the law on discretionary denial evolving quickly, Fintiv remains a hot topic and one to continue watching in 2021. In fact, several technology companies have filed a lawsuit arguing that Fintiv violates the APA and AIA. Apple Inc. et al v. Iancu, Case Number 5:20-cv-06128 (NDCA August 31, 2020). Also, in October, the USPTO signaled potential rule making on discretionary denial by issuing a Request for Comments on Discretion to Institute Trials Before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. 85 Fed. Reg. 66502 (PTO-C-2020-0055, October 20, 2020). With these developments, PTAB law on discretionary denial remains fluid and changes may be coming. In the meantime, however, the Fintiv precedent remains and petitioners would be well-advised to prepare strong petitions, prepare them quickly, and avoid overlap between parallel proceedings to the greatest extent possible.

A Quiet Year for the PTAB Precedential Opinion Panel

Requests for the Director’s review of Board decisions by the Precedential Opinion Panel (“POP”) increased in 2020, but the granting of such review was elusive. According to Docket Navigator, the Director has issued at least 92 decisions on requests for POP review since the POP was created in September 2018. The Director issued at least 49 such orders in 2020 and did not grant a single request for POP review. Indeed, to date, the Director has granted POP review in only four cases—a success rate of less than five percent.

In 2020, the Director issued a single POP decision, which related to whether and when “the Board [may] raise a ground of unpatentability that a petitioner did not advance or insufficiently developed against substitute claims proposed in a motion to amend.” Hunting Titan, Inc. v. DynaEnergetics Europe GMBH, IPR2018-00600, Paper 67, 3 (PTAB Jul. 6, 2020). Interestingly, after the Board granted POP review but before it issued its decision, the Federal Circuit took up a very similar issue and determined that “the Board may sua sponte identify a patentability issue for a proposed substitute claim based on the prior art of record.” Nike, Inc. v. Adidas AG, 955 F.3d 45, 51 (Fed. Cir. 2020). Yet, despite its reviewing court providing what could be viewed as rather broad discretion regarding the grounds the Board may sua sponte raise against substitute claims, the Hunting Titan POP decision significantly curtails that discretion to “rare circumstances” where, for example, the petitioner ceases to participate in opposing the amendment or where “the record readily and persuasively establishes that substitute claims are unpatentable for the same reasons that corresponding original claims are unpatentable.” Hunting Titan, Paper 67 at 12-13.

The POP decision reiterated a number of times that the adversarial process of IPRs is best served by putting the onus on the petitioner to raise grounds against the claims and worried that requiring panels to consider all possible grounds supportable by the proceeding’s entire record would substantially threaten the mandated efficiency of AIA proceedings. See id. at 11-12. Having significantly tied the Board’s hands in considering grounds other than those raised in a petitioner’s opposition, the POP decision pointed parties toward ex parte reexamination as a more appropriate forum for pursuing an “examination approach” to the review of substitute claims. Id. at 19. Whether or not follow-on ex parte reexaminations challenging substitute claims prove useful to petitioners grappling with co-pending litigation remains to be seen.

While the Board’s decision in Hunting Titan is currently binding on the Board’s future decisions, the Federal Circuit has issued opinions that call into question the applicability of such POP decisions outside of PTAB proceedings. Facebook, Inc. v. Windy City Innovations, LLC, 953 F.3d 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2020). In March, the Federal Circuit addressed the Board’s ability to join new issues to an ongoing IPR proceeding via joinder under 35 U.S.C. § 315(c). Id. at 1317-18. (This is the same issue that the POP had addressed in Proppant Express Investments, LLC v. Oren Technologies, LLC, No. IPR2018-00914, Paper 38 (P.T.A.B. Mar. 13, 2019)). The Federal Circuit resolved that the Board’s POP decision was not entitled to Chevron deference because the language of § 315(c) was unambiguous. Id. at 1328. Further, the Federal Circuit opinion also offered lengthy “additional views” expressing the view that POP decisions should be given no deference by a reviewing court. Id. at 1337-44. Specifically, the additional views explained that “[t]here is no indication in the statute that Congress either intended to delegate broad substantive rulemaking authority to the Director to interpret statutory provisions through POP opinions or intended him to engage in any rulemaking other than through the mechanism of prescribing regulations.” Id. at 1340. These views seem to go beyond consideration of appropriate levels of deference and appear to show a broader disdain for the POP process generally.

Yet, despite the Federal Circuit’s indicating a strong likelihood that POP decisions will be given little or no deference in future appeals, the precedent set by the POP still has the power to significantly impact practice at the PTAB—particularly with respect to certain non-reviewable issues. For example, in April 2020, the Supreme Court in Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, LP held that § 314(d)’s bar on appeal of institution decisions “encompasses the entire determination ‘whether to institute an inter partes review.’” Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, LP, 140 S. Ct. 1367, 1375 (2020) (emphasis added). The Federal Circuit has subsequently held that Thryv forecloses its ability to review the Board’s discretionary denials of institution pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 314(a). See, e.g., Cisco Systems Inc. v. Ramot at Tel Aviv University, Case Nos. 20-2047, -2049 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 30, 2020). As a result, certain Board precedent currently stands immune to reconsideration by a reviewing court, and POP decisions related to such issues may accordingly have a lasting impact on the conduct of post-grant proceedings. While the Board chose not to utilize the POP review process to address any such issues in 2020, it is worth watching whether a new USPTO Director will utilize the POP process to clarify or alter the Board’s approach to these or other issues in 2021 and beyond.

Declines in Biopharma Activity at the PTAB

In calendar year (CY) 2020, the total number of post-grant petitions in the biopharma space, which we define as petitions involving USPTO Technology Center 1600 patents, was 85, which accounted for 5% of all petitions filed. This number was less than the 114 petitions filed in CY 2019 and the 144 petitions filed in 2018, indicating that the number of biopharma petitions is on a three-year downward trend. The vast majority in 2020 were inter partes review (IPR) petitions, but 18 PGR petitions were filed. Of the cases that reached an institution decision, 75% were instituted—a slight increase from the approximately 70% instituted in 2019. The most active petitioners in 2020 were 10x Genomics, Inc., Progenity, Inc., and Illumina, Inc. The most active patent owners in 2020 were HandyLab, Inc., United Kingdom Research and Innovation/Harvard University, and Natera, Inc.

.png)

The year was slow for biologics5 at the PTAB. In 2020, only two IPR petitions and one PGR petition were filed against patents covering biologic drugs. This number is down from 14 biologic IPR petitions filed in 2019 and 20 biologic IPR petitions filed in 2018. The first IPR petition concerned a transgenic mouse patent held by Kymab for producing antibodies, which was denied under § 325(d). The second IPR petition, still pending as of the date of publication, was filed against an Amgen biologics method patent not clearly related to any specific product. The single PGR petition, also still pending as of the date of publication, concerned a patent held by SeaGen covering Enhertu® (trastuzumab deruxtecan). Several explanations have been offered for this precipitous decline in filings, including a general slowdown in biologic activity, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and uncertainty surrounding IPR since Arthrex v. Smith & Nephew, No. 18-2140 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 31, 2019).

The Year in Appeals

On November 5, 2020, Fish Senior Principal John Dragseth and Principal Nitika Gupta Fiorella hosted the Post-Grant for Practitioners webinar “Post-Grant Appeals.” In it, they discussed the latest post-grant decisions from the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. If you missed that webinar, you can find a summary of many of the cases they covered below, as well as a few additional cases from the past year.

Legality of PTAB Judges

In Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc., 941 F.3d 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2019), a Federal Circuit panel held that Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) judges were unconstitutionally appointed because they were “principal,” not “inferior,” officers and thus needed nomination and Senate confirmation. But the panel had a fix to avoid obliterating post-grant review altogether: it made the judges terminable at will, to make them “inferior” officers. The Supreme Court accepted review on the following issues: (1) whether the judges were initially invalid, and if so, (2) whether the Federal Circuit’s fix was legitimate. United States v. Arthrex, Inc., Docket No. 19-1434 (cert. granted Oct. 13, 2020). Oral argument will be in early 2021, and we can expect a decision by June or earlier.

Although widely seen as one of the most noteworthy cases this year, the practical effect of Arthrex might not be game-changing outside certain cases. If the Supreme Court affirms, a number of cases that were decided soon after Arthrex will get a rehearing at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO). On the other hand, the Court could decide that the Federal Circuit’s fix is invalid, and there is no judicial fix. Even then, Congress could still work with the PTO to try to fix things. However, it remains uncertain as to how disruptive that would be. Notably, in Ciena Corp. v. Oyster Optics, LLC, 958 F.3d 1157 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (Order), the Federal Circuit said that only patentees can challenge the constitutionality of the APJs, because petitioners chose the IPR option in the first place—so this will cut down on who can complain, even if the Supreme Court rules IPR judges invalid. Bottom line: continue to preserve objections on this ground.

Reviewability

In Thryv, Inc. v. Click-to-Call Technologies, LP, 140 S. Ct. 1367, 206 L. Ed. 2d 554 (2020), the Supreme Court held that a patentee could not challenge the PTAB’s decision to institute a petition that the patentee argued was time-barred. The looming question then is, what PTAB decisions made at institution can the courts review? The Supreme Court’s opinion seems to say that no one—neither patentees nor petitioners—can complain about institution or non-institution, but that has enormous ramifications, particularly on the non-institution side. That is because the PTAB has been declining institution of petitions that it identifies as meritorious for a host of policy-driven reasons, including for efficiency where a patent is involved in a parallel fast-track litigation. So far, no petitions for mandamus have inspired review of such rulings, e.g., Cisco Systems Inc. v. Iancu, No. 20-148, 2020 WL 6373016 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 30, 2020). Pending review, however, is an APA suit filed by several technology companies in the Northern District of California that challenges similar actions by the PTO, Cisco Sys., Inc. et al. v. Iancu, No. 5:20-cv-6128 (N.D. Cal., filed Aug. 31, 2020).

Standing

Congress gave any “person” who is not the patent owner standing to bring an IPR, but Article III of the Constitution limits judicial review of an IPR to cases in which there is a live “case or controversy.” In other words to establish Article III standing for appeal, the losing petitioner must be able to show a concrete and imminent risk of being sued for patent infringement. Since the AIA’s inception, the Federal Circuit has continued to clarify the law on what constitutes “imminent risk” for standing, and 2020 was no different.

For example, in Argentum Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., 956 F.3d 1374, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2020), Argentum appealed a holding that it failed to establish the unpatentability of Novartis’ patent claims to a particular drug. Argentum tried to show risk of suit by pointing to its marketing partner’s plans to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), but the court said that was not enough because (1) Argentum’s marketing partner had not filed the ANDA yet, and (2) if Novartis sued anyone, it would be Argentum’s marketing partner, not Argentum.

On the other hand, the court found standing in Adidas AG v. Nike, Inc., 963 F.3d 1355, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2020), where the patentee had (1) previously sued the petitioner on a different patent; (2) refused to grant the petitioner a covenant not to sue for similar, ongoing conduct; and (3) sued a third party with a similar product to the petitioner’s on the patent in the IPR. Similarly, in Grit Energy Solutions, LLC v. Oren Technologies, LLC, 957 F.3d 1309, 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the court said a petitioner that had previously been sued on the patent had standing where the previous action had been dismissed without prejudice. These cases stand for the principle that injury-in-fact in patent cases require the petitioner-appellant to show more than a generalized fear of infringement; rather, there must be something in the past dealings with the patentee or the nature of the petitioner’s actions that suggest suit is imminent.

Estoppel

Like standing, estoppel is another legal issue that continues to dominate the Federal Circuit’s PTAB appeals docket. The court issued a number of cases this year touching on estoppel that arises between different IPRs and estoppel from IPRs into litigation.

In Papst Licensing GmbH v. Samsung Electronics America, Inc., 924 F.3d 1243 (Fed. Cir. 2019), the court looked at the classic collateral estoppel effect from prior IPRs. In that case, the court found the patentee estopped from challenging the PTAB’s obviousness findings that were common with other IPRs, the appeals of which the patentee had voluntarily dismissed. But in Power Integrations, Inc. v. Semiconductor Components Industries, LLC, 926 F.3d 1306, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2019), the court found no estoppel even where the patentee had already litigated and lost an issue in another IPR, which it chose not to appeal. Unlike Papst, in Power Integrations, the court found the prior patent was not in real dispute between the parties at the time of the decision and, thus, that the patentee had no incentive to fully litigate it.

The court also took on cases involving the more common type of estoppel—where a petitioner is prevented from presenting in litigation prior art that it could have brought in an IPR. See 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2). In Network-1 Techs., Inc. v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 976 F.3d 1301, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2020), for example, the court found a party that joined an IPR after institution was not estopped from raising invalidity challenges in district court based on prior art that could have been, but was not, raised in the IPR. One unanswered question is what happens with estoppels in district court when a petitioner wins an IPR. The court was presented with this issue in BTG Int’l Ltd. v. Amneal Pharms. LLC, where the PTO advocated that a petitioner should be estopped from raising grounds in litigation that it advanced and won in the IPR; the court did not reach the issue but instead decided the case on other grounds. 923 F.3d 1063, 1066 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

Indefiniteness at the PTAB

The Board has long had a policy of not reviewing, in IPR proceedings, claims that are indefinite. In Samsung Electronics America, Inc. v. Prisua Engineering Corp., 948 F.3d 1342 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the Federal Circuit held that the Board cannot invalidate claims for Section 112 issues in IPR, but that a supposed indefiniteness problem (here, claims that fail under IPXL) would not prevent the Board from applying the prior art, as long as the indefiniteness problem did not interfere with such prior art application. So there is space for petitioners to get IPR review of certain indefinite claims. But the Board still can refuse to look at claims whose indefiniteness issues get in the way. For example, in Cochlear Bone Anchored Solutions AB v. Oticon Medical AB, 958 F.3d 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the court found no error in the Board’s refusal to address certain means-plus-function limitations that had no corresponding structure, but faulted the Board on one limitation because the claim recited a physical structure “and/or” the means-plus-function element, so the means-plus-function element was not required.

Constitutionality of IPR for Pre-AIA Patents

The constitutionality of IPR for pre-AIA patents was also at play this year. In Celgene Corp. v. Peter, 931 F.3d 1342 (Fed. Cir. 2019), the Federal Circuit held that IPR challenges to pre-AIA patents are not unconstitutional (i.e., they are not a taking of an issued patent or a violation of due process). The Supreme Court has since denied certiorari on this and several other cases that raised the same issue. And in Personal Audio, LLC v. CBS Corp., 946 F.3d 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the Federal Circuit held that a district court cannot consider arguments that various aspects of IPR are illegal, since a patentee can, and must, make those arguments in IPR.

- https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/20201028_ptab__mta_study_installment_6_tf_iq_813950_final_revised.pdf

- https://www.uspto.gov/blog/director/entry/ptab-s-motion-to-amend

- We define "biologics" as antibodies and the like used in humans. We exclude small peptide drugs (<40aa), animal vaccines, and animal therapeutics.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.