IP Law Essentials

ITC Litigation: The Rise in Popularity of Section 337

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

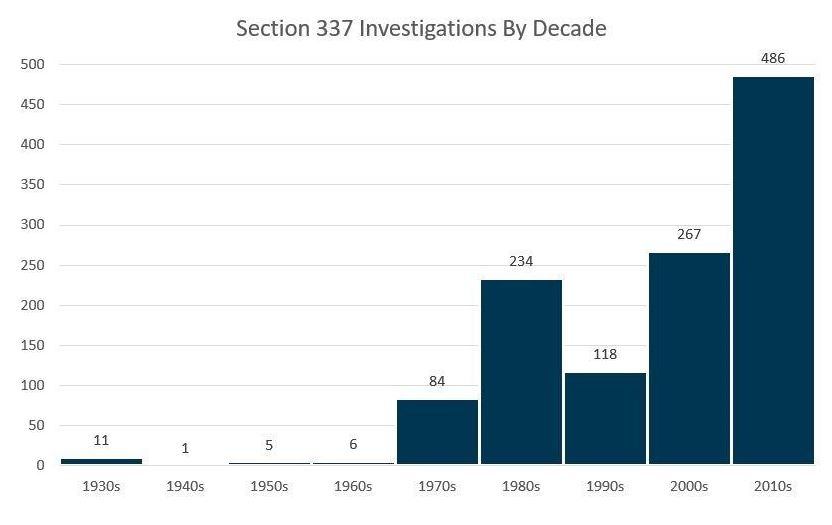

"Section 337" actions before the United States International Trade Commission have existed for decades since their creation under the Tariff Act of 1930. As the below histogram depicts, however, the number of instituted Section 337 investigations in the ITC's first 40 years is less than 5% of that from this past decade, alone.

Here, we trace the roots of ITC Section 337 actions throughout its existence, summarizing a few of what we think are the most notable historical facts concerning the ITC (previously known as the U.S. Tariff Commission):

1930s

- The Commission's role in investigating and reporting unfair acts actually began in 1922, under Section 316 of the Tariff Act passed that year. Congress replaced Section 316 with Section 337 in the Tariff Act of 1930. Section 337 allowed the Commission to make recommendations to the President who would, in turn, decide whether to exclude merchandise from entering the U.S. based on unfair practices in import trade.[1]

- The first Section 337 investigation instituted by the Commission concerned the alleged unfair sale of Russian asbestos in 1931 and was not based on patent infringement.[2] By 1937, however, patent infringement was the principal ground of Section 337 complaints.[3]

- In 1938, the Commission started making public the complaints received under Section 337, and by the end of the decade, the Commission received approximately 34 complaints and instituted 11 Section 337 investigations.[4]

1940s

- Because of World War II, the Commission redirected much of its work to war time efforts and dismissed nearly all of the handful of Section 337 complaints it received.[5]

- The Commission did institute for the first time in eight years a Section 337 investigation in 1943 concerning Canadian-sourced medical swabs judicially found to infringe U.S. patents, but ultimately found no substantial injury to the complainant because imports were suspended under war conditions.[6]

1950s

- The Commission received 21 complaints and instituted five Section 337 investigations in this baby-boom era.[7]

- For two completed investigations in 1957 and in 1959 the Commission did not reach a decision on patent infringement because it found the complainants failed to show a substantial injury or tendency to destroy a domestic industry.[8]

1960s

- The Commission received 11 complaints and instituted six Section 337 investigations.[9]

- In a matter concerning "in-the-ear hearing aids" filed in 1965, the Commission unanimously found patent infringement but evenly split on whether it substantially injured a domestic industry. Section 337 permitted the President to break the tie and find a violation, but President Johnson declined to exercise that option.[10]

1970s

- The number of Section 337 complaints climbed substantially in the 70s. In just the first five years alone the Commission received over 40 complaints and instituted investigations in nearly all cases.[11]

- Momentous changes in the ITC took place in 1975:

- Under the Trade Act of 1974, the U.S. Tariff Commission became the U.S. International Trade Commission.[12]

- Its decisions in Section 337 proceedings were no longer advisory instead, the ITC now made decisions that became final subject to Presidential approval.[13]

- Section 337 proceedings took on the adjudicative form we see today, and the ITC hired its first Administrative Law Judge, Judge Myron R. Renick.[14]

- The ITC began using the "337-TA" nomenclature for identifying investigations by reassigning pending Section 337 investigations new numbers. Certain Electronic Pianos, whose complaint was filed on March 6, 1972, and whose investigation the ITC instituted on March 30, 1972, became Inv. No. 337-TA-1.[15]

- The last investigation that the ITC instituted in the 70s was Inv. No. 337-TA-76, signaling more investigations were instituted in the 70s than all prior decades combined.[16]

1980s

- The ITC instituted 234 Section 337 investigations this decade.[17]

- In 1981, the ITC issued its first temporary exclusion order against the importation of copper rods based on patent infringement and the first limited exclusion order specifically directed at a foreign manufacturer of large video matrix systems (aka scoreboards). The ITC also found for the first time that a domestic industry under Section 337 could be satisfied by a service and distribution industry.[18]

- The ITC observed in 1982 a notable increase in non-patent Section 337 proceedings concerning trademark, copyright, passing off, false designation of origin, and misappropriation of trade secrets accounting for one-third of its total case load.[19]

- This decade saw important changes to Section 337 as part of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988.[20]

- Complainants no longer had to prove injury in order to obtain relief based on infringement of statutory IP rights (e.g. patents, registered trademarks, copyrights, mask works, or registered boat hull designs).[21]

- For investigations based on statutory IP rights, the definition of the required domestic industry was clarified, and extended to include non-manufacturing activities such as licensing, research and development, and engineering.[22]

- In 1989, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) - now the World Trade Organization - ruled on behalf of the European Community and found that several aspects of Section 337 violated the U.S.'s treaty obligations, including:

- The statutorily mandated 12 month deadline for concluding investigations;

- The inability of respondents to raise counterclaims; and

- The fact that a foreign manufacturer may have to defend itself in both the ITC and a federal court simultaneously while a domestic manufacturer only faced litigation in federal court.[23]

1990s

- The ITC instituted approximately 118 Section 337 investigations this decade.[24]

- In 1994, Congress passed the Uruguay Round Agreements Act which had provisions addressing the 1989 GATT Panel report:

- The statutory time limit was replaced by language directing the ITC to conclude investigations "at the earliest practical time";[25]

- Respondents could now raise counterclaims that are removed to district court;[26] and

- A respondent facing actions in the ITC and in district court may have the court action stayed.[27]

- In 1995, the ITC launched a website providing online access to its reports, opinions, and notices.[28]

- In 1996, the ITC instituted its first investigation alleging infringement of registered mask works in Inv. No. 337-TA-384, In the Matter of Certain Monolithic Microwave Integrated Circuit Downconverters.[29]

- This decade marked the beginning of a 15-year streak where women comprised at least half of the Commissioners in the ITC.

2000s

- The ITC instituted approximately 267 Section 337 investigations through the end of 2009 more than double the number from the 1990s.[30]

- By 2000 and 2001, for example, the ITC experienced a 60% increase in its Section 337 caseload.[31]

- Instituted investigations on average lasted 12.7 months before termination.[32]

- Over this decade, approximately 94% of the Section 337 investigations alleged patent infringement, 7% alleged trademark or trade dress infringement, 2% alleged copyright infringement, and less than 2% alleged misappropriation of trade secrets or false advertising.[33]

2010s

- The ITC instituted approximately 486 Section 337 investigations, of which 431 have terminated.[34]

- Instituted Section 337 investigations on average lasted 11.3 months before termination.[35]

- In 2013, the ITC launched the Section 337 100-day pilot program, intended to expedite proceedings. Specifically, this program permits the ITC to direct ALJ to issue an early initial determination on a potentially dispositive issue within 100 days of institution.[36]

- In June 2018, the ITC formally added the 100-day program to its rules.[37]

- Over this decade, approximately 95% of the Section 337 investigations alleged patent infringement, 6% alleged trademark or trade dress infringement, 2% alleged copyright infringement, and 2% alleged misappropriation of trade secrets, tortious interference, false advertising, false designation of origin or manufacturer, or conspiracy to fix prices and control output and export volumes.[38]

2020s

- As of the end of April, the ITC instituted seven Section 337 investigations. For comparison purposes, in the same time period in 2019, the ITC instituted 11 Section 337 investigations.[39]

- At this time, and until further notice, the ITC is only accepting electronic filings. In April, alone, four complaints were filed according to these new procedures.[40]

More questions? Contact the authors or visitFish's Intellectual Property Law Essentials.

[1] Fifteenth Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 3 (1931); A Centennial History of the USITC, USITC Pub. 4744, at 317-19 (Nov. 2017).

[2] Fifteenth Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 75-76 (1931).

[3] Twenty-first Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 36 (1937).

[4] Twenty-second Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 31, 49 (1938); Twenty-third Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 37 (1939); Twenty-fourth Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 37 (1940).

[5] Twenty-fourth Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 37 (1940); Twenty-fifth Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 43 (1941); Twenty-sixth Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission (1942) (containing no reports of Section 337 activities); Twenty-seventh Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 19-20 (1943); Twenty-eighth Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission (1944); Section 337 Status Report, USITC Pub. 130, at 1 n.1 (July 1964).

[6] Twenty-seventh Annual Report of the U.S. Tariff Commission 19-20 (1943).

[7] Section 337 Status Report, USITC Pub. 130 (July 1964) (summarizing Section 337 activity from Jan. 1949 to July 1964).

[8] Id.

[9] Id.; Annual Report FY 1964, USITC Pub. 146 (Feb. 1965); Annual Report FY 1965, USITC Pub. 168 (Jan. 1966); Annual Report FY 1966, USITC Pub. 193 (Dec. 1966); Annual Report FY 1967, USITC Pub. 227 (Jan. 1968); Annual Report FY 1968, USITC Pub. 273 (Jan. 1969); Annual Report FY 1969, USITC Pub. 301 (Nov. 1969); Annual Report FY 1970, USITC Pub. 356 (Jan. 1971).

[10] Annual Report FY 1967, USITC Pub. 227, at 9-10 (Jan. 1968).

[11] Annual Report FY 1970, USITC Pub. 356 (Jan. 1971); Annual Report FY 1971, USITC Pub. 467 (Mar. 1972); Annual Report FY 1972, USITC Pub. 536 (Jan. 1973); Annual Report FY 1973, USITC Pub. 649 (Jan. 1974); Annual Report FY 1974, USITC Pub. 710 (Jan. 1975); Annual Report FY 1976, USITC Pub. 790 (Nov. 1976).

[12] A Centennial History of the USITC, USITC Publication 4744, at 122 (Nov. 2017).

[13] Id. at 333.

[14] A Centennial History of the USITC, USITC Publication 4744, at 132, 334 n. 902 (Nov. 2017).

[15] Annual Report FY 1976, USITC Pub. 790 (Nov. 1976).

[16] Information compiled from Lex Machina based on dates of Notice of Institution as published in the Federal Registrar. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[17] Information compiled from Lex Machina based on dates of Notice of Institution as published in the Federal Registrar. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[18] Annual Report FY 1981, USITC Pub. 1352, at 11 (Feb. 1983).

[19] Annual Report FY 1982, USITC Pub. 1412, at 11 (Aug. 1983).

[20] The ITC also moved to its current address at 500 E Street SW in 1988. Annual Report FY 1991, USITC Pub. 2490 (Feb. 1992). If you ever stay in the Hotel Monaco in D.C., you're staying in the pre-1988 ITC building. See A Landmark History: A Historic Hotel in Washington DC, https://www.monaco-dc.com/historic-hotels-washington-dc/ (last visited May 4, 2020).

[21] Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-418, 1342, 102 Stat. 1107, 1212, 1215 (codified as amended at 19 U.S.C. 1337). Congress added boat hull designs to the scope of statutory IP protection under Section 337 in 1999. Act of Nov. 29, 1999, Pub. L. No. 106-113, 113 Stat. 1501, 1501A-594.

[22] Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-418, 1342, 102 Stat. 1107, 1212-13 (codified as amended at 19 U.S.C. 1337(a)(3)(C)).

[23] Report of the Panel, United States-Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, L/6439 (Nov. 7, 1989), GATT B.I.S.D. at 36S/345 (1990).

[24] Information compiled from Lex Machina based on dates of Notice of Institution as published in the Federal Registrar. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[25] Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. 103-465, 321, 108 Stat. 4809, 4943 (1994) (codified as amended at 19 U.S.C. 1337(b)(1)); see also A Centennial History of the USITC, USITC Pub. 4744, at 327-28 (Nov. 2017).

[26] Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. 103-465, 321, 108 Stat. 4809, 4943-4944 (1994) (codified as amended at 19 U.S.C. 1337(c)); see also A Centennial History of the USITC, USITC Pub. 4744, at 327-28 (Nov. 2017).

[27] Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. 103-465, 261 and 321, 108 Stat. 4908-4910, 4943-4946 (1994) (codified as amended at 28 U.S.C. 1659); see also A Centennial History of the USITC, USITC Pub. 4744, at 327-28 (Nov. 2017).

[28] Annual Report FY 1995, USITC Pub. No. 2979, at 11 (Sep. 1996).

[29] Annual Report FY 1996, USITC Pub. No. 3025, at 14 (Apr. 1997); 61 Fed. Reg. 10595 (Mar. 14, 1996).

[30] Information compiled from Lex Machina based on dates of Notice of Institution as published in the Federal Registrar. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[31] USITC Year in Review, USITC Pub. No. 3520, at 11 (June 2002).

[32] Information compiled from Lex Machina based on time between Notice of Institution as published in the Federal Registrar and termination dates. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[33] Information compiled from Lex Machina, including investigations that included more than one type of claim. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[34] Information compiled from Lex Machina based on dates of Notice of Institution as published in the Federal Registrar. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[35] Information compiled from Lex Machina based on time between Notice of Institution as published in the Federal Registrar and termination dates. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[36] Faster Investigation Resolution, Lower Litigation Costs Are Goals of USITC Section 337 Pilot Program, USITC News Release 13-059 (June 24, 2013), https://www.usitc.gov/press_room/news_release/2013/er0624ll2.htm.

[37] Rules of General Application, Adjudication and Enforcement, 83 Fed. Reg. 21140, 21160, 21162 (May 8, 2018) (codified at 19 CFR 210.10, 210.42).

[38] Information compiled from Lex Machina, including investigations that included more than one type of claim. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[39] Information compiled from Lex Machina. See Lex Machina, https://lexmachina.com/ (last visited April 28, 2020).

[40] USITC Response to COVID-19, https://www.usitc.gov/press_room/featured_news/usitc_response_covid_19.htm (last visited Apr. 24, 2020).

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.