Blog

IP and Cannabis: The Current Landscape

Fish & Richardson

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Senior Patent Agent

-

- Name

- Person title

- Associate

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

Authors: Keith Barritt, Frank Gerratana, Steven Katz, Steffen Lake, Jon Jekel, Angela Parsons

Cannabis[i] is a rapidly growing industry; in 2019, overall sales of cannabis products legal under state law were estimated to be worth $13.6 billion, with an expected increase to $29.7 billion by 2025.[ii] While marijuana remains a Schedule I controlled substance under federal law, a majority of states have legalized consumption of certain cannabis products under certain conditions. As of the date of publication, 36 states and the District of Columbia have legalized cannabis for medical use, while 15 states and the District of Columbia have legalized it for adult recreational use.[iii] This tension between state and federal law presents obstacles for cannabis entrepreneurs. As with any growing industry, cannabis stakeholders are eager to protect their valuable intellectual property (IP) rights, but their ability to obtain comprehensive IP protection and enforce their IP rights is sometimes in conflict with federal drug law. Nevertheless, the current IP landscape surrounding cannabis, while very much in flux, does allow for some forms of IP protection and enforcement.

For more information about any topic herein, please see our October 20, 2020 webinar, "IP and Cannabis: The Current Landscape," or contact your Fish attorney.

FDA Regulation

Until 2018, cannabis in almost all of its forms was regulated as a Schedule I controlled substance — the same category used for heroin and LSD. But shifting social attitudes toward cannabis use, coupled with a widespread relaxation of state drug laws, led to a recognition that not all "cannabis" is the same; the cannabis plant contains over 80 biologically active compounds, the most well-known of which are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). The 2018 Farm Bill removed hemp from the definition of "marijuana" in the Controlled Substances Act. Under the new guidelines, "hemp" refers to cannabis and its derivatives containing no more than 0.3% THC. However, the bill did not eliminate the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) purview over products containing hemp, nor did it remove cannabis with over 0.3% THC from Schedule I.

The 2018 Farm Bill led to widespread availability of products containing CBD, which are commonly marketed as dietary supplements, drugs, food, and cosmetics. The FDA's policies concerning the legality of such substances are as follows:

- CBD in drugs: The use of CBD in drugs (i.e., products intended for the cure, treatment, or prevention of disease or conditions) requires the submission of a New Drug Application, including clinical studies of effectiveness for the intended indication. The FDA approved its first drug containing CBD as an active ingredient, Epidiolex, in 2018.

- CBD in dietary supplements and food: Because CBD was in clinical trials for Epidiolex prior to what the FDA considers to have been "lawful" marketing of CBD, the FDA's position is that CBD cannot be a lawful ingredient in dietary substances â dietary supplements or food — without the submission of an application for approval as a "new dietary ingredient." However, the FDA has found that hemp seed, hemp seed protein powder, and hemp seed oil are "generally recognized as safe" and those products may be used in supplements or food.

- CBD in cosmetics: The FDA does not pre-approve cosmetic ingredients, but may ban ingredients that are harmful. As CBD has not been banned, cosmetic products that contain CBD may be marketed for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance of the human body. But making non-cosmetic claims for the product (e.g., "improves mood" or "soothes aching muscles") would push it out of the "cosmetics" category.

The FDA has no formal deference to state laws that have legalized cannabis products, but its recent enforcement activity has been sparse. In November 2019, the agency sent warning letters to 15 companies, but it has taken little further action since then. A new CBD policy is reportedly under development by the FDA.

Trademark

Trademark protection is available for cannabis companies (canna-brands) through a combination of federal, state, and common law sources. Federal trademark registration is the strongest form of protection, as it is nationwide in scope and gives potential infringers constructive notice by virtue of being published in the Trademark Register. State-level trademark registrations confer many of the same advantages as federal registration, but are limited to the state in which the mark is registered. Common law trademark rights are automatically created upon the use of a trademark in commercial activities, but are the narrowest in scope, and are limited only to the geographic area of commercial use.

While federal trademark registration is the strongest form of protection, it also presents the greatest challenges for canna-brands, as most forms of cannabis are considered illegal substances under federal law. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) typically rejects cannabis trademark applications on one or more of the following legal grounds:

- The Controlled Substances Act, which prohibits the manufacture and distribution of cannabis products containing more than 0.3% THC — even if such products are legal under state law.

- The "use in commerce" requirement, which requires the applicant to provide evidence that it has placed the mark on the goods and sold them to an actual, bona fide consumer in a manner that is lawful under federal law.

- The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which requires premarket approval from the FDA for food and dietary supplements that contain substances undergoing clinical investigations for the treatment of medical issues. Because CBD is an active ingredient in the FDA-approved drug Epidiolex, the USPTO will commonly reject trademark applications even for cannabis products that are legal under the Controlled Substances Act. Products containing hemp seed, hemp seed protein powder, and hemp seed oil are exempt from the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and are not subject to related trademark rejections.

With large segments of the cannabis industry excluded from the benefits of federal trademark registration, canna-brands must seek trademark protection through a patchwork of federal, state, and common law strategies. For canna-brands whose products are legal under state law but illegal under federal law, state-level trademark registrations provide the strongest protection for core products, while common law rights and unfair competition claims can fill gaps where needed. Federal trademark registration may still be available to canna-brands for federally legal goods or services — usually products that are ancillary to the core product, such as websites, clothing items, and mobile apps.

Patent Prosecution

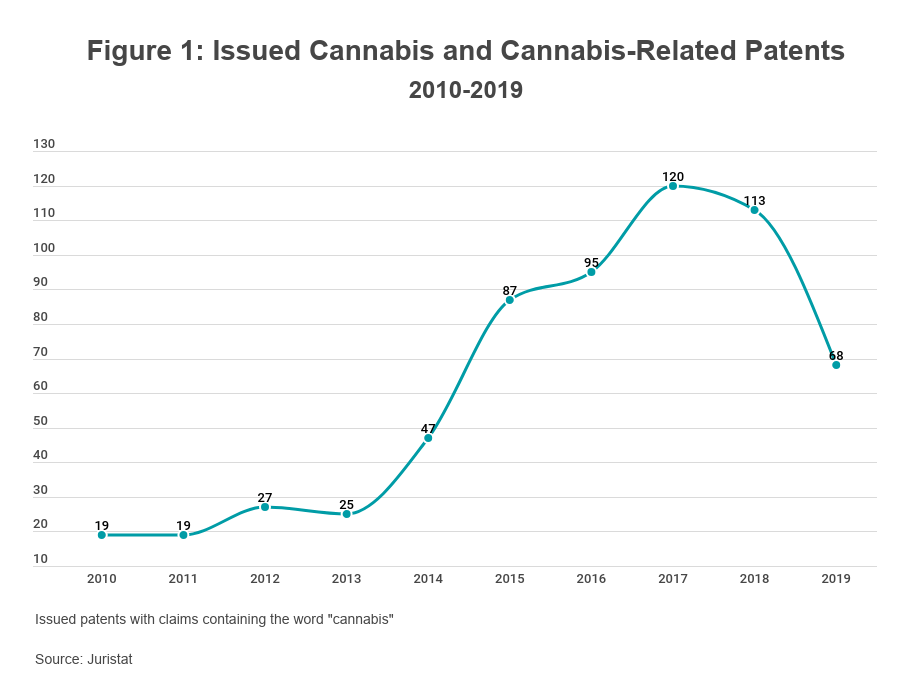

Patent protection is generally available for cannabis and cannabis-related innovations on the same basis as any other innovation, presenting relatively few obstacles for applicants. In the past 10 years, the USPTO has issued hundreds of cannabis-related patents (see Figure 1). While most claim secondary technologies (e.g., cultivation methods, processing and extraction techniques, cannabis-derived products, consumption devices, and medical treatments), some claim new strains of the cannabis plant itself.

The USPTO is willing to issue patents on cannabis irrespective of its legality because patent rights are merely negative rights; a patent is the right to exclude others from the invention claimed therein rather than a license to make, use, or sell the invention. Unlike trademark registrations, there is no requirement that a patent applicant demonstrate that it has used the claimed invention in commerce. A patent applicant's planned use of the claimed invention thus has no bearing on its patentability.

The primary challenges for cannabis patent applicants are subject-matter eligibility rejections and the comparative lack of traditional prior art publications in the field. As with many life sciences patents, cannabis patents are subject to rejections under § 101 as claiming laws of nature or natural phenomena. Applicants should therefore take cues from the biopharma and agricultural spaces by claiming only genetically modified strains, compounds, formulations, dosage forms, methods of treatment, and methods of extraction/purification. The comparative lack of prior art in the field stems from cannabis' long-standing criminalization; before the widespread legalization of cannabis, entrepreneurs who had developed innovative products were reluctant to publish their findings for fear of criminal prosecution. As a result, much of the prior art in the cannabis space is informal, nonscientific literature that is not collated or indexed in a traditional manner. The absence of a well-developed body of formal prior art raises the danger that the USPTO will issue invalid or overly broad patents due to very limited information or proof of prior use.

Patent Litigation

The landscape surrounding cannabis patent litigation is uncertain at best. To date, no court has issued a finding of infringement of a cannabis patent, although the District of Colorado has at least considered the issue (see more below). As such, whether federal courts will be willing or able to enforce cannabis patents remains an open question.

The enforcement of patent rights is governed exclusively by federal law, and federal law continues to classify most forms of cannabis as Schedule I controlled substances. While the USPTO issues patents on cannabis-related innovations without regard to their legality, federal courts may be more constrained in their ability to enforce cannabis patent rights. This is primarily due to the centuries-old Illegality Doctrine, which holds that a court may not enforce claims or contracts that are based in illegal acts. The Illegality Doctrine is well-settled and has been widely applied in American law to prevent a party from benefiting from acts that are "illegal, criminal, and void...[in] a court whose duty is to give effect to the law which the party admits he intends to violate." Higgins et al. v. McCrea, 116 U.S. 671 (1886). In the context of cannabis patents, courts may refuse to hear an infringement claim on the grounds that the patentee is attempting to protect its own criminal enterprise from competition from another criminal enterprise. Contracts, such as cannabis patent licenses, could also be unenforceable under federal law.

It is unclear whether the Illegality Doctrine applies to cannabis patent infringement cases, as no court has yet held that it does. However, plenty of scholarship suggests that the doctrine should not apply in the cannabis patent context. While cannabis itself is illegal under federal law, cannabis patents are not illegal; a patent is a government grant of property rights rather than the "fruit of a crime," thereby distinguishing patent cases from traditional Illegality Doctrine cases. Further, a patent is the right to exclude. By enforcing a cannabis patent owner's rights against an infringer, the court is merely stopping the infringer from doing something that is illegal under federal law.

Even if a court were to hear a cannabis patent infringement case, a successful patentee could nonetheless face difficulties obtaining remedies. In direct competitor scenarios, a cannabis patentee may have the easiest time obtaining an injunction, as the court would merely be stopping the competitor from engaging in illegal activity. Obtaining monetary damages could be more difficult. While a cannabis patent itself may not be the fruit of a crime for Illegality Doctrine purposes, profits derived from selling cannabis products likely could be considered as such, thereby giving the defendant an opportunity to argue that no damages are available. Further remedies, including attorneys' fees and seizure, destruction, or impoundment of infringing goods, are available only in exceptional cases, and it remains unclear whether the courts would award them in a cannabis patent infringement case.

The closest the courts have come to settling the question of whether cannabis patents are enforceable is United Cannabis Corp. v. Pure Hemp Collective, Inc., No. 18-cv-1922-WJM-NYM, filed July 30, 2018, in the District of Colorado. United Cannabis (UCANN) filed a complaint against Pure Hemp asserting U.S. Patent No. 9,730,911, which claimed various liquid formulations of highly enriched extracts of plant cannabinoids, including formulations wherein at least 95% of the total cannabinoids are THCa, THC, CBD, CBDa, THC + CBD, and CBD + CBN + THC. Pure Hemp moved for partial summary judgment, arguing that the claims were unpatentable because they were directed to natural phenomena. The court denied Pure Hemp's motion, finding that the claims did not claim patent-ineligible subject matter under Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014). The case was subsequently stayed due to UCANN's filing of a bankruptcy petition. Nonetheless, United Cannabis provides a few insights into how courts may handle cannabis infringement claims going forward. Most notably, the court did not raise the Illegality Doctrine, despite having the power to do so. That the court was willing to hear the case at all and that the case survived past the summary judgment stage is an early indicator that cannabis patent holders will be able to use the federal courts to enforce their patents.

[i] In this article, we use the term "cannabis" as an umbrella term for hemp, marijuana, or any extracts of hemp/marijuana, such as CBD or THC. For more information on how the FDA treats "cannabis" and "hemp," see the FDA's guidelines.

[ii] https://newfrontierdata.com/cannabis-insights/u-s-legal-cannabis-market-growth/

[iii] https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.