Blog

Massachusetts Patent Litigation Wrap Up — April 2020

Fish & Richardson

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

This post is a part of a monthly series summarizing notable activity in patent litigation in the District of Massachusetts, including short summaries of substantive orders.

As a general matter, the public emergency arising out of the coronavirus epidemic has prompted numerous changes in the court's procedures. Notably, on May 27, 2020, the court issued a General Order continuing all jury trials in the District of Massachusetts scheduled to begin on or before September 8, 2020. The format of other types of hearings generally remains within the discretion of individual judges, many of whom have been receptive to using a videoconference format. To the extent access to the courthouse is required, the court recently issued a Standing Order requiring the wearing of masks in public spaces.

Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. v. Covidien LP, No. CV 16-12556-LTS, 2020 WL 1969914 (D. Mass. Apr. 24, 2020)

On April 24, 2020, Judge Sorokin issued findings of fact and rulings of law following a bench trial. Ethicon sought a declaration that its Enseal X1 Large Jaw vessel sealer did not infringe two of Covidien's patents and that the patents were invalid. Covidien counterclaimed infringement. The court found that Ethicon failed prove that the two patents at issue are invalid. And the court held that Covidien failed to establish that Ethicon infringed either patent.

The patents at issue relate to "features of advanced bipolar surgical instruments used to seal and cut tissue or blood vessels." The accused devices "permit surgeons to grasp a vessel or tissue[,] apply energy to the vessel or tissue to form a seal[,] and then cut the sealed tissue . . . ."

United States Patent No. 9,241,759

Claim Construction:

The parties disputed whether the '759 patent's preamble reciting "endoscopic bipolar forceps" was a claim limitation. The court found that it was not because it "merely describe[d] a purpose or intended use for the invention, and [also because] the claim body describe[d] a structurally complete invention," noting that "the specification does not limit the invention to instruments used endoscopically."

Infringement:

The parties disputed whether the accused product practiced "a movable handle . . . that includes [] 'a finger loop' and [] 'a drive flange' . . . ." present in each asserted claim of the '759 patent.

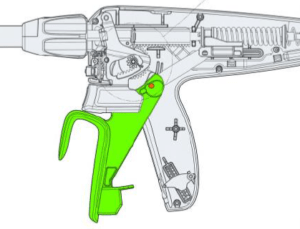

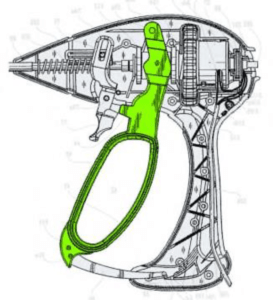

The court found that the shepherd's hook design of the movable handle in the Enseal X1 (left image, below) did not practice the '759 patent's "finger loop" limitation (right image, below) under the doctrine of equivalents, including under either the insubstantial differences or function-way-result tests:

|

|

The court reasoned that "[t]here are meaningful differences between the [claimed] finger loop and the [accused device's] shepherd's hook handle, which are grasped and released differently, and which 'receive' the user's fingers differently." The court further rejected Covidien's arguments that Ethicon's own patents and filings in a separate litigation showed equivalence.

The court previously construed "drive flange" to mean "a force-actuating and projecting rib," and in this order clarified that "a 'rib' is material added to strengthen or reinforce a part" and is not limited to "thin strips." The court agreed with Covidien that "raised structures projecting from each side of the [accused device's] movable handle" are "ribs." But the court found that the raised structures were not "force-actuating and projecting" since both parties agreed that removing the raised structures "does not prevent the transmission of force . . . ." In other words, the structures were "not the only portion of the handle to transmit force exerted by the user." The accused device thus did not practice the "drive flange" limitation and did not infringe.

Invalidity:

Ethicon argued that the '759 patent was obvious over U.S. Patent No. 6,419,675 ("Gallo"), which "does not teach several of the limitations recited in independent claim 1 of the '759 patent," in view of one or more other pieces of prior art. The court disagreed because "Ethicon points to no disclosure in the cited prior art or in any other source that suggests the desirability—at the time of the invention of redesigning the jaw members, shaft and shaft assembly, the mechanism used to close the jaw members, and the movable handle of Gallo in the ways required to produce the device covered by the claims of the '759 patent." The court also found it important that Ethicon's expert witness "did not consider the amount of time or resources it would have taken to modify Gallo to produce the '759 patent device."

United States Patent No. 8,323,310

Claim Construction:

The court construed "plane," used in the claim phrase "when the jaw members are disposed in the [clamped] position, a plane is formed between the opposing sealing surfaces," to mean "the plane that bisects the gap between the sealing surfaces when the jaw members are in the closed position." In making this construction, the court rejected Ethicon's arguments that the "plane" limitation requires "the sealing surfaces [to] touch when the jaw members are in the closed position" or, alternatively, that "the claimed 'plane' is indefinite because a gap contains an infinite number of planes and the patent offers no guidance to determine which of these is the claimed plane." The court found that Ethicon's construction was contrary to the "only figure in the patent showing the jaw members in a closed (or "clamped') position" that "shows a gap between the sealing surfaces of the jaw members," and that descriptions of other embodiments cited by Ethicon did not serve to limit the claims.

Infringement:

The court found that Covidien failed prove that the accused devices include a "plane that bisects the gap between the sealing surfaces of the jaw members when they are in the closed position [and that] is below the longitudinal axis" as required by the claims of the '310 patent. To prove that this limitation was met, Covidien relied on a CAD assembly file and photographs of the accused devices—not measurements of the physical accused devices. The court found that the CAD assembly file "is not reliable for mapping the precise spatial relationships of components of a device whose dimensions are not stable, or a reliable basis for determining precise distances between components of manufactured devices" in light of manufacturing tolerances. The court found that Covidien failed to show that "using photographs to measure the minuscule distances at issue here is a reliable approach" while describing several issues with Covidien's expert's methodology.

Invalidity:

Ethicon argued that certain figures in three prior art references anticipated or render obvious the claims of the '310 patent. The parties disputed whether the figures in the references disclosed the plane limitation. Relying on "well settled" Federal Circuit precedent providing that "arguments based on drawings not explicitly made to scale in issued patents are unavailing," Nystrom v. TREX Co., Inc., 424 F.3d 1136, 1149 (Fed. Cir. 2005), the court found that none of the references invalidated the claims because the references did not disclose "that the figures at issue [were] drawn to scale or that they define[d] the precise proportions of components or the relationships among components . . . ."

Intellectual Ventures I, LLC v. NetApp, Inc., No. CV 16-10860-PBS, 2020 WL 1644227 (D. Mass. Apr. 2, 2020)

On April 2, 2020, Judge Saris granted NetApp's motion for summary judgment finding that NetApp did not infringe U.S. Patent No. 6,516,442.

The '442 patent relates to a "type of computer architecture known as a symmetric multi-processor system, in which multiple computer processors share a common operating system and memory." The patent "sought to improve how data is transferred through the components of a symmetric multi-processor system in order to increase the system's processing capacity."

Intellectual Ventures ("IV") accused NetApp's MetroCluster systems. The MetroCluster systems "allow[ed] a user to continuously back up data in a separate location . . . ."

The primary issue before the court was whether the MetroCluster systems had certain components configured to "perform error correction of the data," which the court previously construed to require "correcting errors in data by at least reconstructing erroneous data." For this limitation, IV pointed to the MetroCluster systems' "cyclic redundancy check" ("CRC") code used "[t]o ensure that data is transmitted correctly from one component to the other." NetApp countered that CRC codes were solely error detecting codes instead of error correcting codes as required by the claims.

The court found that the CRC code did not meet the error correction limitation because it never "'reconstruct[s] erroneous data' . . . as required by th[e] Court's Claim Construction Order." Rather, "the CRC code's only function is to trigger a retry request, at the exclusion of any other method of addressing errors."

IV also argued that an infringement analysis is a question of fact that precluded summary judgment, citing Uniloc USA, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 632 F.3d 1292, 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2011). The court disagreed, explaining IV's infringement theory "contradicts the Court's construction of" the "error correction" limitation. The court further ruled that "IV cannot relitigate claim construction at the summary judgment stage and then cry dueling experts."

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.