Post-Grant Report

2018 Post-Grant Annual Report

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

2018 WAS A WATERSHED YEAR FOR POST-GRANT PRACTICE

The Supreme Court of the United States and the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued several important decisions touching on a variety of topics, including the constitutionality of inter partes review (IPR) proceedings under Article III, real party in interest (RPI) and privity issues, partial institution decisions, and printed publications. The Supreme Court of the United States and the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued several important decisions touching on a variety of topics, including the constitutionality of inter partes review (IPR) proceedings under Article III, real party in interest (RPI) and privity issues, partial institution decisions, and printed publications. The Supreme Court of the United States and the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued several important decisions touching on a variety of topics, including the constitutionality of inter partes review (IPR) proceedings under Article III, real party in interest (RPI) and privity issues, partial institution decisions, and printed publications.

Fish’s 2018 Post-Grant Report takes a deep dive in to the cases, trends, and statistics that shaped post-grant practice over the previous year and how they will affect practitioners going forward.

PTAB Firm of the Year

Managing Intellectual Property, 2018

The Year in Post-Grant at the Supreme Court

April 24, 2018, was a big day for post-grant proceedings. That day, the Supreme Court issued two highly anticipated decisions on post-grant proceedings: Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group, LLC, which considered the constitutionality of IPR, and SAS Institute, Inc. v. Iancu, which considered the PTAB’s practice of partially instituting IPR petitions. Oil States, in particular, had piqued widespread media attention because of its potential to dismantle the entire post-grant process.

In Oil States, the justices found that IPR did not violate Article III of the Constitution or the Seventh Amendment. IPR would survive because patents are a public right—specifically, a public franchise, not a private one—and thus do not merit an Article III proceeding or jury.

Notably, the majority decision did not clad IPR, or post-grant more generally, against further constitutional challenges. The Court made clear that its opinion “addresses the constitutionality of inter partes review only,” leaving covered business method (CBM) and post-grant review (PGR) open to attack. Moreover, the Court also hinted at other challenges that might have merit, observing that “Oil States does not challenge the retroactive application of inter partes review” and had “failed to raise a due process challenge.” Thus, while IPR survived this constitutional attack, there could be more to come.

Later that day, the Court issued its opinion in SAS. Despite being, comparatively, a procedural nit, SAS has had the greater impact. Justice Gorsuch, this time writing for the majority, ended the PTAB practice of partial institutions. The Court reasoned that the plain language of § 318(a)—“the [Board] shall issue a final written decision with respect to the patentability of any patent claim challenged by the petitioner”—imposed a nondiscretionary duty on the PTAB to address every claim a petitioner has challenged. The PTAB implemented the edict in SAS as a binary choice—trial must be either instituted for all claims or denied for all claims.

Binary institution has changed the post-grant landscape in a number of ways. Not surprisingly, SAS can lead to more complex proceedings. For example, in the institution decision, the majority of panels will comment negatively on grounds and claims they feel do not pass muster. The comments provide the parties guidance on what grounds are in play. Nonetheless, if the proceeding is instituted, petitioners can now continue to argue the negatively treated grounds. The 2018 Trial Practice Guide update reinforces this practice, making explicit the petitioner’s right to reply to issues in the institution decision. An open question, however, is whether petitioners will be able to introduce new evidence to bolster these grounds. The Board’s practice also adds complexity, increasing the number of potential issues present at the oral argument and in the final written decision.

SAS also affects the estoppel arising from many post-grant proceedings. Per Shaw Industries Group, Inc. v. Automated Creel Systems, estoppel does not attach to grounds presented but not instituted. Under SAS, if a petition is granted, estoppel will eventually attach to all presented grounds and claims because the final written decision will address all presented grounds and claims. Therefore, in the normal course, less prior art is sheltered from estoppel. And petitioners intending to employ the Shaw-based strategy of including additional prior art grounds that might be preserved against estoppel if not instituted must do so at the cost of filing a separate petition.

Finally, binary institution has other impacts. For example, because the PTAB’s discretion can no longer be exercised on a ground-by-ground basis, it is possible that a petition that passed muster for one or a few claims but was otherwise largely weak may be discretionally denied in its entirety.

While post-grant survived its first fundamental challenge in Oil States and has mostly come to terms with the effects of SAS, it will be interesting to see what is in store for post-grant in 2019.

2018: A Time of Change and Transition at the PTAB

While practice and procedure at the PTAB have progressively advanced and evolved since its inception, 2018 was particularly lively in terms of meaningful change.

FROM BRI TO PHILLIPS

On May 9, 2018, the USPTO published a proposed rule change that would (a) modify the claim construction standard in post-grant proceedings from BRI to the standard applied in federal district courts under Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005), and (b) require PTAB panels to review and consider prior claim construction rulings from a district court or International Trade Commission proceeding. See 83 Fed. Reg. 21221, 21222 (PTO-P-2018-0036, May 9, 2018). More than 350 comments were submitted in response to the proposal, including 75 comments from intellectual property organizations and business entities. On balance, the interested public seemed receptive to the change, and the office announced its implementation on October 11, 2018, for all petitions filed on or after November 13, 2018. See 83 Fed. Reg. 51340 (PTO-P-2018-0036, October 11, 2018). While the change in claim construction standard came as no surprise to most, its entirely prospective application was far from certain and led to a significant spike in petition filings (80+ petitions were filed on November 12). This rush to file undercuts views expressed by certain commenters and the USPTO itself that the BRI and Phillips standards are not significantly different. It seems many petitioners believe the latter is considerably narrower. With the rule change being prospective, clashes between BRI and Phillips interpretations at the PTAB may be few and far between, leaving the practical effect of this shift difficult to measure.

NEW GUIDANCE AND PROPOSAL ON CLAIM AMENDMENTS

At the close of 2017, now-former USPTO Chief Judge Ruschke provided guidance on the PTAB’s policy under Aqua Products, Inc. v. Matal, 872 F.3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2017), indicating that the burden of persuasion with respect to patentability of substitute claims would not be placed on the patent owner. Beyond this modification, Chief Judge Ruschke indicated that the practice and procedure regarding amendments would not change. This largely held true until June 1, 2018, when Western Digital Corp. v. Spex Technologies, Inc., IPR2018- 00082, Paper 13 (April 25, 2018), was designated informative in replacement of MasterImage 3D, Inc. v. RealD, Inc., IPR2015-00040, Paper 42 (July 15, 2015), and Idle Free Sys., Inc. v. Bergstrom, Inc., IPR2012-00027, Paper 26 (June 11, 2013). Western Digital provided new and much-needed guidance on a variety of topics, including the ordinary treatment of requests to substitute claims as contingent, the presumption that one substitute claim per replaced challenged claim is reasonable, and the authority of the Board to find substitute claims unpatentable based on any evidence of record in the proceeding. While Western Digital’s guidelines offer increased predictability and certainty for the current amendment process, the USPTO’s recently proposed pilot program is an entirely new framework that may make motions to amend more attractive for patent owners. See 83 Fed. Reg. 54319 (PTO-P-2018-0062, October 29, 2018). The pilot program features an accelerated briefing schedule that calls for a preliminary, nonbinding evaluation of a motion to amend by the Board and an opportunity for the patent owner to revise the amendment before the oral hearing and final written decision. From a patent owner’s perspective, this may compare favorably with the current regime, where there is only one opportunity to submit an amendment before the motion is ruled on at the final written decision. The USPTO indicated that it anticipates implementation of the pilot program “shortly after the comment deadline” of December 14, 2018, and it will be “used in every AIA [America Invents Act] trial proceeding involving a motion to amend.” See 83 Fed. Reg. at 54324.

THE TRIAL PRACTICE GUIDE UPDATE

In August 2018, the PTAB published an update to its original Trial Practice Guide of 2012. Of the many topics addressed, considerations regarding institution are perhaps the most notable. Here, the Practice Guide update reemphasizes considerations beyond the merits of patentability, including the 325(d) Becton Dickinson factors and the General Plastic factors considered in assessing follow-on petitions. In addition to these specific doctrines, the Practice Guide update notes that under 35 USC 316(b), an institution decision should broadly consider the integrity of the patent system, the efficient administration of the USPTO, and the ability of the USPTO to timely complete proceedings. Some observers have opined that the 316(b) consideration can be leveraged to justify denial of instituting the petition as a whole under SAS, even where one or more grounds have merit. Of further interest is the provision of a guaranteed sur-reply for patent owners, combined with the option to request a sur-rebuttal at the oral hearing. While these aspects generally favor patent owners, the Practice Guide update includes revisions sure to be welcomed by petitioners as well. For example, petitioners now have express authorization to address in the reply brief any point raised by the Board’s institution decision. Thus, grounds unfavorably received by the Board yet instituted under the PTAB’s post-SAS policy may be addressed, even if the patent owner’s response is silent on the subject.

Changes to the RPI and Privity Issues in 2018

The Wi-Fi One (en banc) Federal Circuit decision, which came out in January 2018, made the one-year IPR time bar under 35 USC 315(b) appealable for the first time. See Wi-Fi One, LLC v. Broadcom Corp., 878 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (en banc). In doing so, this decision opened the door for the Federal Circuit to weigh in on PTAB treatment of the RPI and privity inquiries. And the Federal Circuit wasted no time in providing guidance, issuing a string of four seminal cases in short order over the past year: (1) Wi-Fi One, LLC v. Broadcom Corp. (Wi-Fi Remand), 887 F.3d 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2018); (2) WesternGeco, LLC v. ION Geophysical Corporation, ION International S.A.R.L. (WesternGeco), 889 F.3d 1309 (Fed. Cir. 2018); (3) Applications in Internet Time, LLC v. RPX Corporation (AIT), 897 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2018); and (4) Worlds, Inc. v. Bungie, Inc. (Worlds), 903 F.3d 1237 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

In Wi-Fi Remand, the Federal Circuit affirmed various aspects of the USPTO Trial Practice Guide’s guidance on the RPI and privity inquiries, including its recognition that the terms “privy” and “real party in interest” should be governed by common-law principles. The Federal Circuit agreed that the privity inquiry requires a “flexible” analysis to determine whether the relationship between two parties is “sufficiently close such that both should be bound by the trial outcome and related estoppels,” and that the RPI inquiry requires the Board to determine whether some party other than the petitioner is the “party or parties at whose behest the petition has been filed.”

The Federal Circuit provided further guidance on the privity issue in WesternGeco, noting that the privity inquiry “is a highly fact-dependent question” that requires the Board to engage in a “flexible” analysis on a “case by case” basis. The Federal Circuit affirmed that the Taylor framework introduced by the Supreme Court in Taylor v. Sturgell is useful in performing the privity inquiry. See 128 S.Ct. 2161. Additionally, the Federal Circuit stated that (a) a common desire among multiple parties to invalidate a patent alone is insufficient to establish privity, (b) a standard customer-manufacturer relationship regarding the accused product alone is insufficient to establish privity, and (c) an indemnification agreement alone does not necessarily establish privity, as it depends on the specifics of the agreement.

The Federal Circuit then turned to the RPI inquiry in AIT, where, unlike in Wi-Fi Remand and WesternGeco, it vacated the Board’s final written decisions and remanded the cases to the Board for further consideration. In vacating the Board’s decisions, the Federal Circuit noted that the Board had adopted an overly narrow interpretation of “real party in interest,” had failed to consider the entirety of the administrative record, and had misallocated the burden of proof by placing it on the patent owner rather than on the petitioner. The Federal Circuit noted that determination of whether a nonparty is an RPI “demands a flexible approach that takes into account both equitable and practical considerations, with an eye toward determining whether the nonparty is a clear beneficiary that has a preexisting relationship with the petitioner.”

According to the Federal Circuit, the Board erred by focusing too heavily on the lack of evidence of control and funding of the particular IPRs by the nonparty while turning a blind eye to other types of proxy relationships that may be implicated, including whether the petitioner was an express or implied litigating agent for the nonparty and whether the conduct of the petitioner and the nonparty gave the petitioner apparent authority to act on behalf of the nonparty in pursuit of the nonparty’s desires. The Federal Circuit also faulted the Board for failing to consider the nonparty’s interests in the IPRs, the nature of the petitioner’s business model, the overlapping members on the petitioner’s and the nonparty’s boards of directors, and the pattern of communication and the exchange of payments between the nonparty and the petitioner that may be indicative of a willful blindness strategy.

In Worlds, the Federal Circuit addressed the Board’s burden framework for performing the RPI inquiry. In analyzing the burden framework heretofore used by the Board as set forth in Atlanta Gas Light v. Bennet Regulator Guards (IPR2013-00453), the Federal Circuit agreed that the petitioner bears the burden of persuasion as to the accuracy of its initial identification of RPIs, and that the initial identification should be accepted unless and until disputed by the patent owner. The Federal Circuit, however, disagreed that the petitioner’s initial identification should act as a “rebuttable presumption” shifting a burden of production to the patent owner. Instead, the Federal Circuit clarified that the acceptance of initial identification is “practical,” not a presumption, and that the patent owner need produce only “some evidence” to raise the RPI issue and thereby trigger the petitioner’s obligation to satisfy its burden of persuasion. The Federal Circuit did not address the quantum of support needed to raise the RPI issue but noted that the Atlanta Gas Light standard, if not treated as a presumption, requiring evidence that “reasonably brings into question the accuracy of a petitioner’s identification of the real parties in interest,” may prove useful.

RPI and privity are hot issues at the PTAB and merit close watching in 2019.

2018 Developments in the Biopharma Sector

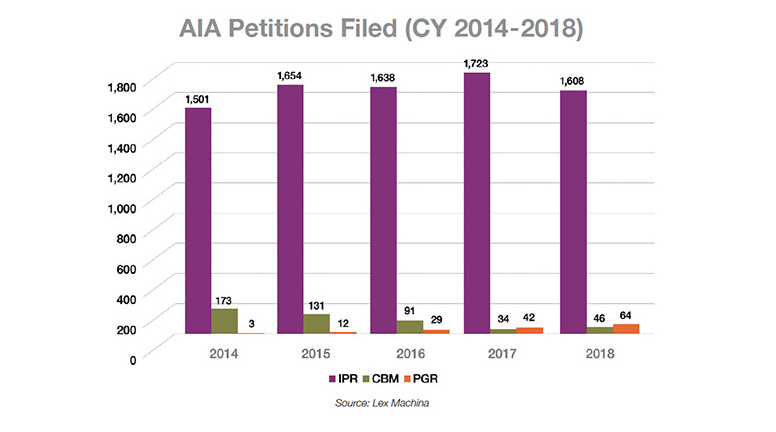

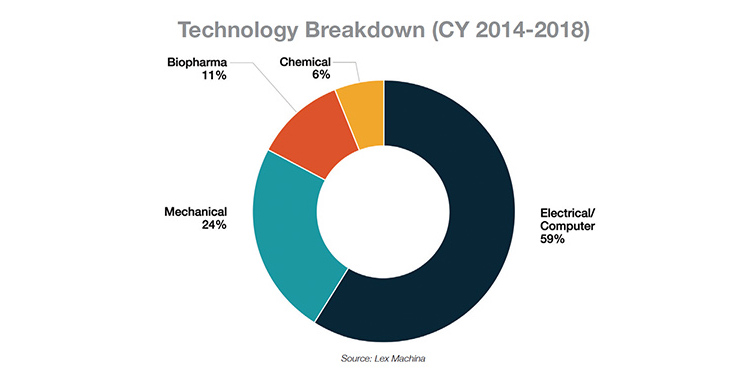

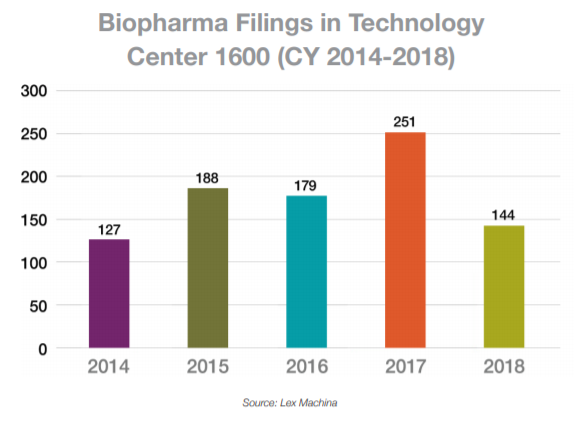

In calendar year (CY) 2018, the total number of post-grant petitions in the biopharma space, which we define as petitions involving Group 1600 patents, was 144 petitions filed, which accounted for 8 percent of all petitions filed. This number was down from the record-setting 251 petitions filed in 2017. The vast majority in 2018 were IPR petitions, but 21 PGR petitions were filed. Of the cases that reached an institution decision in the biopharma space, approximately 63 percent were instituted, which was slightly less than the average institution rate of 70 percent across all technology classes. The most active petitioners in 2018 were Eli Lilly, Foundation Medicine, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The most active patent owners in this space were Teva Pharmaceuticals, Caris MPI, and GlaxoSmithKline.

2018 also saw a marked difference in the number of IPR petitions against patents covering biologic drugs. While 2017 was a record year for biologic petitions as well, with over 80 petitions filed, only a quarter of that number (20) were filed in 2018. The number of petitions filed in 2018 was more consistent with the number of biologic petitions filed in 2015 and 2016 (17 and 20, respectively). The high number of petitions filed in 2017 was largely a result of multiple petitions focused primarily on three blockbuster drugs: Herceptin (31 petitions), Rituxan (19 petitions), and Humira (14 petitions). While there were multiple petitions filed on particular drug portfolios in 2018 (for example, Eli Lilly filed nine petitions challenging nine patents related to galcanezumab), there were not as many biologic patent portfolios challenged, nor to the same degree, as in 2017.

Another notable development related to biopharma IPRs in 2018 was the introduction of the Hatch-Waxman Integrity Act of 2018 by Senator Orrin Hatch (R-Utah). The proposed legislation would modify the IPR process for pharmaceuticals—under Hatch-Waxman and the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA)— “to restore the careful balance the Hatch-Waxman Act struck to incentivize generic drug development.” The proposed legislation would apply to both generic and biosimilar drug applicants, requiring anyone wishing to challenge a pharmaceutical patent to choose between Hatch-Waxman/BPCIA litigation and an AIA challenge (IPR). The legislation is currently under consideration.

2018 Federal Circuit Decisions that Will Impact PTAB Practice

Several decisions interpreted § 315(b), which prohibits the PTAB from instituting an IPR filed more than a year after the petitioner, a privy, or an RPI is sued for infringement. The Federal Circuit held in Wi-Fi One that it has jurisdiction to review those determinations, which has led it to overturn multiple aspects of the Board’s prior practice (see Page 4).

Addressing another aspect of the time bar, Click-to-Call Techs., LP v. Ingenio, Inc., 899 F.3d 1321 (Fed. Cir. 2018), held that the one-year clock starts anytime a petitioner is sued for infringement, even if that suit is later dismissed without prejudice. The court rejected the Board’s approach, instead focusing on the statutory text, which refers to the suit’s “filing,” making whatever happens later irrelevant. The court took a similarly literal view of another provision—§ 311(a)—holding that its instruction that any “person who is not the owner of a patent may file” an IPR means that assignor estoppel cannot bar institution. See Arista Networks, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 908 F.3d 792 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

Other decisions addressed whether a petitioner who loses at the Board has standing to appeal. Standing currently requires an injury beyond a mere loss at the Board. Two decisions found standing where the appellant had just begun potentially infringing activity or had sufficiently concrete plans to do so, even if the activity might not begin for several years. See Altaire Pharms., Inc. v. Paragon BioTeck, Inc., 889 F.3d 1274 (Fed. Cir. 2018); E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co. v. Synvina CV, 904 F.3d 996 (Fed. Cir. 2018). But a party didn’t have standing where it could not quantify the risk it might infringe and insisted that its design “will continue to evolve and may change.” JTEKT Corp. v. GKN Automotive, Inc., 898 F.3d 1217 (Fed. Cir. 2018). Several other standing appeals are pending at the Federal Circuit. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court has signaled interest in addressing standing in RPX Corp. v. ChanBond, LLC, No. 17-1686, by asking for the solicitor general’s views.

A recurring issue of substantive patent law in IPR appeals was whether various references were “publicly accessible” and thus prior art. See Medtronic, Inc. v. Barry, 891 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (vacating the Board finding that a video and slides shown to at least 75 expert surgeons at two conferences weren’t prior art); Jazz Pharms., Inc. v. Amneal Pharms., LLC, 895 F.3d 1347 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (materials on the FDA website were prior art, especially when a Federal Register notice indicated their location); Nobel Biocare Services AG v. Instradent USA, Inc., 903 F.3d 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (a catalog distributed at a conference was prior art where witnesses provided the conference’s date and one had an old copy in his files); GoPro, Inc. v. Contour IP Holding, LLC, 908 F.3d 690 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (reversing the Board and holding that a catalog distributed at a trade show without restriction was prior art where the show involved technology related to the patent-in-suit, regardless of whether it was “directly” available to skilled artisans); and Acceleration Bay, LLC v. Activision Blizzard, Inc., 908 F.3d 765 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (a thesis wasn’t prior art where it was indexed only by author and year, not title or subject, especially where the university’s search functionality was unreliable).

Finally, the Federal Circuit began applying SAS by remanding decisions where the Board had partially instituted on only some claims or some invalidity grounds. See, e.g., Adidas AG v. Nike, Inc., 894 F.3d 1256 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (collecting cases).

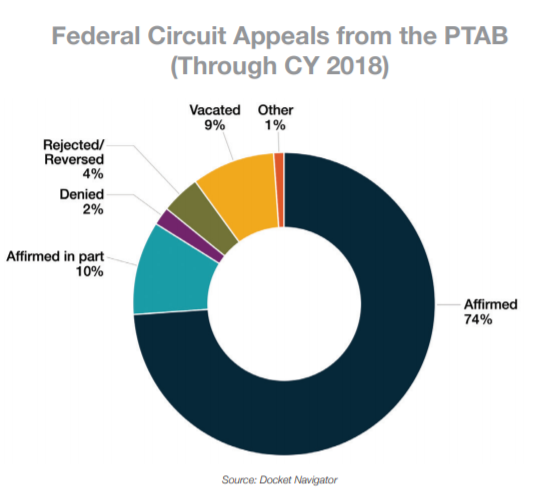

From a landmark Supreme Court case affirming the constitutionality of post-grant proceedings to incremental procedural updates, 2018 saw many changes in the post-grant legal landscape that will impact the practice for years to come. But in a practice as young as post-grant, these kinds of changes are to be expected as the system grows and evolves to meet the needs of the wider business and innovation communities.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.