Post-Grant Report

2015 Post-Grant Annual Report

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Senior Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

-

- Name

- Person title

- Principal

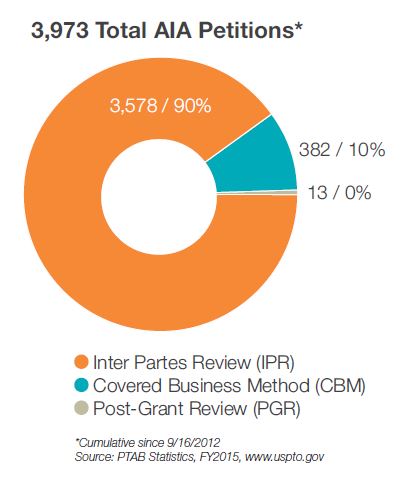

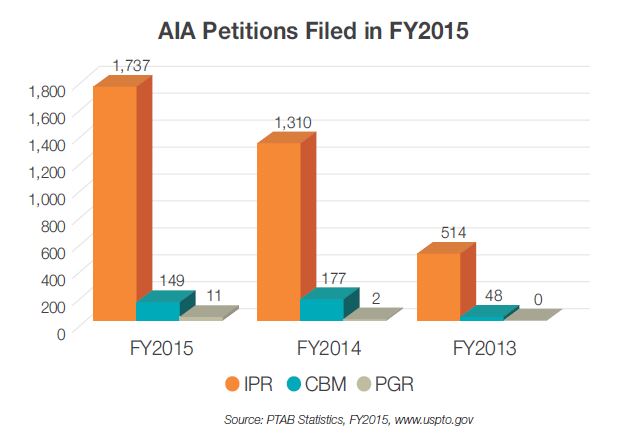

Since the enactment of the America Invents Act (AIA) in September 2012, post-grant proceedings have become an important part of litigation strategy, and in some instances are helping reduce the time and cost associated with litigation.

Fish & Richardson’s 2015 Post-Grant Practice Report takes a closer look at the key issues from the past year in post-grant practice, with particular focus on inter partes review (IPR). Throughout this report, we provide insight on trends and offer practical analysis for your business and patent strategy.

Fish is one of the most active firms at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) according to Managing Intellectual Property, and is also the most active firm representing Petitioners at the PTAB.

For practitioners and those looking to learn more about post-grant proceedings, our team provides a number of practical tools through our dedicated website, fishpostgrant.com, including:

- Monthly webinars covering post-grant topics, including recent decisions, lessons learned, practice tips, and trends.

- Detailed case summaries and decisions, including articles published by members of our post-grant practice.

- Link to download Fish & Richardson’s post-grant app, which delivers up-to-date post-grant content to your mobile device.

We invite you to contact your Fish attorney or a member of our Post-Grant practice with your questions and comments.

New Rules for Post-Grant Proceedings

The USPTO has proposed and instituted a number of new rules for post-grant proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”). They fall into two categories: the “quick fix” and the “second round.”

The “quick fix” rule package was finalized on May 19, 2015, and was effective immediately to institute a number of “quick” changes to post-grant rules. Probably the biggest rule change was in page limits. The page limit was increased from 15 to 25 in Petitioner’s Reply, which makes it much easier to respond to the 60-page Patent Owner response. The page limit was also increased from 15 to 25 in both the Patent Owner’s Motion to Amend and the Petitioner’s Opposition to Motion to Amend, as well as from 5 to 15 pages in the Reply to Opposition. In addition, proposed claim amendments can now be included in an appendix, which does not count as part of the page limit. This alleviates one of the big hurdles to amending claims: too little space to make all the required showings. The quick fix also required the use of Times New Roman font in response to parties’ use of smaller fonts that allow more words per page.

Additional clarifications and minor procedural changes were made, including requiring evidence objections to be filed instead of served, making the statement of material facts optional, allowing more than one backup counsel to be designated, requiring fees paid for unchallenged claims from which a challenged claim depends, and other discovery and procedural rules.

On August 20, 2015, the USPTO issued the “second round” of proposed rule changes. They include:

- Allow Patent Owners to include expert or other declarations with the preliminary response. Supporting evidence will be viewed in the light most favorable to the Petitioner, and the Petitioner may also seek leave to file a reply.

- Apply the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) claim construction standard in proceedings where the patent will expire after a final written decision, and apply Phillips claim construction to patents expiring before a final written decision.

- Require seven days between exchange of exhibits and the oral hearing. Require a word count (not page limit) for briefing. For example, the 60-page limit would be replaced with a 14,000-word limit.

- Add a Rule 11-type certification for all papers filed, to allow the Board to sanction noncompliance.

The addition of a declaration with the preliminary response and the optional reply may prove to be one of the biggest changes. They have the potential to increase costs for parties pre-institution, and also complicate the issue of which facts can be relied on by the PTAB at institution. The move to word count is a small but wise decision, as it should reduce disputes over formatting and improve readability. The addition of the Rule 11-type certification is controversial, but it is not clear how much practical impact it would have. These proposed rules have not yet been implemented, and time will tell which rules get implemented as proposed.

Real Party-in-Interest

A party petitioning for inter partes review (IPR) is required to name all real parties-in-interest (RPIs)—this helps ensure proper application of statutory estoppel and assists the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) in identifying potential conflicts. The determination of whether a party is an RPI is based on a highly fact-specific test, and the case law indicates that the analysis largely hinges on factors such as compensation for filing and control of the IPR proceedings.

There are risks associated with improperly naming RPIs. An IPR may be denied or terminated for failure to name all RPIs, and the failure may not be able to be cured if more than one year has passed since the Petitioner or RPI was served with an infringement complaint.1 The PTAB has considered RPI issues even after institution of trial, and has terminated the proceedings for failure to name all RPIs, where the one-year bar is implicated.2 There is also a risk of being over-inclusive in naming RPIs because estoppel applies to the Petitioner and any named RPI, barring them from further challenging claims based on any ground that was or could have been raised during the IPR.

As noted, the RPI analysis is highly fact dependent. Former Chief Judge James Donald Smith, PTAB, observed that “[c]ourts and commentators agree … that there is no bright-line test for determining the necessary quantity or degree of participation to qualify as a real party-in-interest.”3 The Board generally accepts the Petitioner’s identification of the RPIs. The Patent Owner, however, may rebut the Petitioner’s identification of RPIs.4 In its analysis, the Board considers six “Taylor factors” but has primarily focused on control of and payment for the proceeding.5 In general, an RPI must have sufficient opportunity to control the IPR, such as when a parent wholly owns a Petitioner and authorizes its budget and plans.6 Evidence of payments for specific challenges may indicate an RPI, but nonspecific payments by technical/industry organization members have been found to not be enough.7

Common counsel or participation in related district court proceedings, by itself, is typically not sufficient to establish a third party as a RPI.8 Yet common counsel, when combined with other factors may be sufficient to establish a third party as a RPI8 where it (1) pays the Petitioner for services, including potential IPR filings, and (2) discusses the Patent Owner and filing of IPRs with the Petitioner.9

The RPI analysis will continue to be a highly fact-specific inquiry, and Petitioners must be mindful of the above considerations when filing an IPR, particularly where a Petitioner is part of a larger corporate structure or involved in a joint defense group as part of concurrent district court proceedings. We expect this area of practice to continue to evolve as more fact patterns are considered by the PTAB.

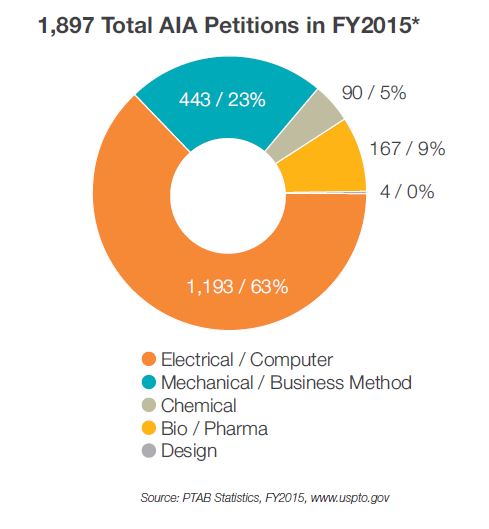

IPR Petitions in BioPharma Grow in Popularity

The popularity of IPR petitions in the biopharma space has steadily grown since 2012 when IPRs were first introduced as a means of challenging the validity of patents. In 2013, 34 IPRs were filed, and the number nearly tripled in 2014 with 97 IPRs filed. With 168 IPRs filed through December 2015, biopharma cases now represent over 9% of all IPR filings. Given this growing trend, it is an opportune time to evaluate the IPR activity in this space.

First, statistics published by the PTO suggest IPR petitions are instituted less often in the biopharma space compared with IPR petitions in other technological classes. For example, as of September 2015, IPRs were instituted 48.4% of the time in non-biotech fields, whereas only 40.5% of biopharma IPRs were instituted. Furthermore, once instituted final decisions are reached in the biopharma context more often, suggesting biopharma cases are less likely to settle. In particular, 65.7% of biopharma trials are completed, as compared with 57.7% of all IPR petitions. PTO statistics further reveal that biopharma claims are less likely to be invalidated by the PTAB in instances in which a final written decision is reached. Collectively, these numbers demonstrate that biopharma IPRs as a class evidence unique trends, of which practitioners in this space should be aware.

Second, review of biopharma IPR petitions reveals that not only are generic and branded companies filing, but so are nonpracticing entities—specifically hedge fund managers. In early 2015, Kyle Bass, founder of Dallas-based hedge fund Hayman Capital Management, announced plans to challenge 15 drug companies’ patents via IPR. As of November 30, 2015, Bass and his various real parties-in-interest, which include Erich Spangenberg, delivered as promised, filing 35 IPR petitions along the way. In sum, 16 companies were the subject of the various petitions, including Acorda Therapeutics, Pozen, Biogen, and Celgene. To date, a decision on institution has been reached in 15 of the 35 cases, with IPR being instituted in seven of these cases.

While Bass has publicly stated his intention in filing IPRs is to invalidate weak biopharma patents to clear the way for lower-priced generic entry, many believe his motives lie in using IPR petitions as part of his investment strategy in which he attempts to profit from short-selling the stock of targeted companies. While the PTAB has refused to dismiss Bass’ petitions as abuse of process, legislative reform that would prevent hedge funds from filing IPRs is being considered.

In response to allegations that their motives are not altruistic, Bass and Spangenberg recently filed two IPR petitions—this time as individuals—against Alpex Pharma and Fresenius. The petitions state that neither stands to profit financially from these filings. In a similar vein, Spangenberg recently used his blog to solicit volunteers to file IPR petitions challenging allegedly “weak” pharma patents, pledging to provide draft petitions to the volunteers and help offset the costs associated with the petitions.

It will be interesting to see how the industry reacts to these filings, and what action, if any, Congress takes in response.

Legislative Developments

Amidst a spate of high-profile IPR filings in the life sciences space by hedge fund financiers, the biotechnology industry has mobilized behind two chief legislative strategies designed to limit or eliminate its exposure to post-grant challenges.

First, medical device, pharmaceutical, and diagnostic companies have sought to change two key provisions in the IPR statute: elevating the burden of proof for invalidity from a preponderance of the evidence to clear and convincing evidence, and narrowing the claim construction standard from the “broadest reasonable construction” of a claim term to its “ordinary and customary meaning,” as used in district court.

Senator Chris Coons (D-Del.) has pushed for these changes in S. 632, the STRONG Patents Act, which he introduced in February 2015. While the Senate has yet to vote on the measure in its entirety, the Senate Judiciary Committee in June approved a different bill, S. 1137, the PATENT Act, which incorporated the “ordinary and customary meaning” change but not the burden of proof provision, and also empowered the Patent Office director to decline institution if it “would not serve the interests of justice.”

In parallel, the House Judiciary Committee in June approved H.R. 9, the Innovation Act, by a 24-9 margin, a bill that incorporated the “ordinary and customary meaning” language from the Coons act but, like the Senate companion measure, not the burden of proof provision. The Innovation Act also includes language that impairs the ability of hedge funds to hold “financial instruments” of the companies whose patents they challenge.

At the same time, the biopharma industry has trod a second path involving the exemption of life sciences patents entirely from the IPR system.

In a July letter to Congress, the Biotechnology Industry Association and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America wrote that IPR “threatens to disrupt the careful balance that Congress achieved over 30 years ago, by increasing business uncertainty for innovative biopharmaceutical companies having to defend their patents in multiple venues and under differing standards and procedures.”

Rep. Mimi Walters (R-Calif.) acted on this proposal, introducing an amendment to the Innovation Act that would have excluded biotech patents from IPR, but she withdrew the amendment in the face of opposition.

Meanwhile, a leaked analysis by the Congressional Budget Office concluded that the BIO/PhRMA proposal would cost the federal government $1.3 billion over the next 10 years because of the delayed entry to market of generic drugs. Biotech industry spokespeople disputed the report, arguing, among other things, that $130 million per year amounted to a very small sum, relatively speaking.

In any event, patent reform in general has stalled in both the House and Senate, leaving the fate of these IPR amendments and proposed exemptions highly uncertain. And in an election year, it’s unlikely that these measures will see much action in Congress.

Joinder in Post-Grant Proceedings

The complex nature of modern patent litigation has meant that multiple defendants often have interests that align around a single portfolio of patents. This inevitably results in one or more post-grant challenges. The natural desire for each party to present its own validity defense can result in a large number of post-grant petitions.

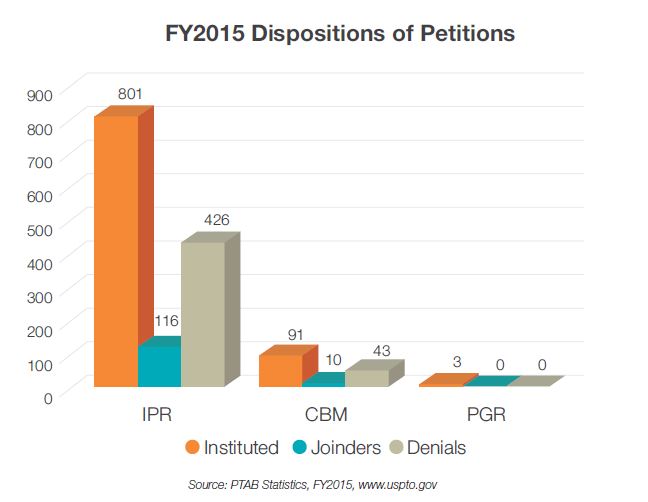

As noted elsewhere in this report, the PTAB often considers joinder in association with 35 U.S.C. § 325(d) as a way of managing the complexity imposed by a large number of challenges. Once two proceedings had been joined, the PTAB often sought to simplify the proceedings in 2015 by mandating that all correspondence flow through the senior Petitioner, where the senior Petitioner is typically the first filer. Thus, the PTAB has seemingly been responsive to concerns by junior Petitioners that a proceeding could settle and be terminated without an opportunity for them to avail themselves of the validity questions raised by the senior Petitioner. In balancing these concerns, the PTAB has allowed parties to liberally join using nearly identical petitions with a request for joinder under 35 U.S.C. § 315(c). Of more than 174 joinder motions filed in 2015, 74% were granted. This rate is markedly increased from granted joinder motions at a rate of 61% in 2014 and 53% in 2013, and is believed to reflect the PTAB’s increased reliance on 35 U.S.C § 325(d). The acceptance rate for joinder motions is below 50% so far in 2016, across 13 requests for joinder.

A brief survey of the reasons for denial of a request for joinder includes concerns about the impact of ongoing proceedings. In the case of IPR2015-01053, the PTAB declined to join a Petitioner filed more than one year after the proceedings where the Petitioner was previously denied institution and filed after the statutory bar by including a new ground for rejection. In the case of IPR2015-01091, the petition was denied for being filed more than three months after the institution date of the earlier petition in which the junior Petitioner sought joinder. The Board in this proceeding went to great lengths to contrast the present proceedings, in which a newly filed petition was being considered, relative to IPR2013-00495, in which the Petitioner sought to join an earlier-filed proceeding on identical grounds.

The PTAB has generally vested the senior Petitioner filing the earlier-considered petition with sole responsibility for preparing a response in joined proceedings. For example, in a scheduling order involving CBM2015-00059, the PTAB joined a junior Petitioner involved in a later-considered petition to earlier-instituted proceedings.

However, the PTAB charged the senior Petitioner involved with the earlier-instituted petition with sole responsibility for filing all joint motions and, conducting cross-examinations, and also noted that the Patent Owner is not required to provide separate discovery responses or additional deposition time as a result of the consolidation. The deference to the senior Petitioner also extended to the oral hearing, where the PTAB allocated time in all proceedings only to the senior Petitioner, and noted that the senior Petitioner is “free to divide the time among the cases as they choose.”

The PTAB tried to strike a compromise that balances the desire for judicial efficiency and prompt resolution of post-grant proceedings in a way that also serves the public interest function in adjudicating exclusive rights. The PTAB struck this balance in 2015 by granting an increased number of joinder motions, albeit often limited to existing records, while preventing junior parties from presenting additional evidence and more current briefing on additional case law.

Shifts in Amendments at the PTAB

Despite another year of attempts to amend in IPR and CBM, success is still rare. But is a change coming?

In the summer of 2015, the PTAB issued its final written decision in REG Synthetic Fuels LLC v. Neste Oil OYJ, IPR2014-00192, only the fourth substantive amendment granted since inception of the AIA post-grant procedures. Perhaps pressured by continued criticism for its seemingly unattainable bar, the PTAB in REG Synthetic seems to have shown a slight easing of its stringent requirements.

Just a year prior, in ScentAir Technologies, Inc. v. Prolitec, Inc., IPR2013-00179, the PTAB had rejected a motion to amend for failing to distinguish prior art cited on the face of the patent, but the panel in REG Synthetic Fuels came to a different conclusion. The panel distinguished ScentAir and allowed an amendment over several references from the face of the patent noted by Petitioner. The PTAB reasoned that, unlike the reference in ScentAir, the references in the REG Synthetic Fuels IPR were not alleged by the challenger to form any part of a combination of references rendering the claims obvious. Rather, these references were relevant only to the question of teaching away, which had been discussed during, and rendered moot by, the PTAB’s rejection of the original claims.

Shortly after REG Synthetic Fuels, the PTAB further clarified the requirements for motions to amend in MasterImage 3D, Inc. v. RealD Inc., Case IPR2015-00040, slip op. at 1-3 (PTAB July 15, 2015) (Paper 42). Here the PTAB explained that a Patent Owner need only argue for the patentability of the proposed substitute claims over the prior art of record, including any art provided in light of a Patent Owner’s duty of candor, and any other prior art or arguments supplied by the Petitioner. In other words, the universe of art the Patent Owner must distinguish is finite.

The decisions in REG Synthetic Fuels and MasterImage illustrate how the PTAB is trying to accommodate amendments, but neither is a big shift.

What’s more, this summer the Federal Circuit effectively gave the PTAB great freedom in its analysis over amendments. The PTAB’s reasoning for rejecting the motion to amend in ScentAir, and more generally the PTAB’s requirements for motions to amend set forth in Idle Free Systems, Inc. v. Bergstrom, Inc., IPR2012–00027 (PTAB June 11, 2013), have since been affirmed at the Federal Circuit. See Prolitec, Inc. v. ScentAir Technologies, Inc. December 4, 2015; Microsoft Corp. v. Proxyconn, Inc.

The First Wave of Post-Grant Appeals

2015 brought the first wave of Federal Circuit decisions in appeals from inter partes review (IPR) and covered business method (CBM) proceedings. The trend has been deference: in 83 post-grant appeals, the Federal Circuit has affirmed in 92%, mostly without opinion. There are a few areas, though, in which the Federal Circuit has addressed interesting new issues.

Several parties have challenged the Board’s authority to institute an IPR or CBM. The Federal Circuit has largely rejected such challenges, finding that the appeal bar in 35 U.S.C. § 314(d) deprives it of jurisdiction to consider most of them. For example, In re Cuozzo Speed Techs., LLC, 793 F.3d 1268 (Fed. Cir. 2015), the Federal Circuit declined jurisdiction over a challenge to the Board’s decision to institute based on an obviousness combination that wasn’t precisely articulated in the IPR petition. Cuozzo held that the § 314(d) appeal bar applies equally at the final written decision stage and that the Petitioner’s failure to cite particular prior art against specific claims wasn’t a basis for upsetting the final decision. But the Federal Circuit has examined one institution-related issue: Versata Development Group v. SAP America, Inc., 793 F.3d 1306 (Fed. Cir. 2015). It found jurisdiction to consider whether the PTAB properly determined a patent was a “covered business method,” because this was a substantive limit on the PTAB’s invalidation authority.

The Supreme Court may soon resolve the seeming tension between Cuozzo and Versata, as it has granted certiorari in Cuozzo and will render a decision there by June 2016.

Most losing parties have framed their appeals as matters of claim construction, as this gets de novo review when based on the intrinsic evidence. But this is still a difficult road for Patent Owners, because Cuozzo held that the “broadest reasonable interpretation” (BRI) standard governs. That result sparked considerable controversy–five judges dissented from denial of rehearing en banc, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari to resolve the issue.

Applying the current BRI standard, the Federal Circuit has reversed claim constructions in only two IPR appeals: Microsoft v. Proxyconn, 789 F.3d 1292 (Fed. Cir. 2015) and Straight Path IP Group v. Sipnet, 806 F.3d 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2015). The common thread was that the Board ignored express limitations in the claim language. By contrast, Patentees are unlikely to succeed in obtaining a narrower construction if the issue is in any way ambiguous or they are relying heavily on the specification.

The Federal Circuit has rejected most appeals arguing either side of obviousness because the Appellant usually reargues underlying factual findings. The only precedential decision that vacates an obviousness finding is Ariosa Diagnostics v. Verinata Health, Inc., 805 F.3d 1359 (Fed. Cir. 2015), where the Board might have erroneously excluded a prior art document that reflected the skilled artisan’s knowledge, regardless of whether it was part of a formal obviousness combination. Another notable decision is Belden Inc. v. Berk-Tek LLC, 805 F.3d 1064 (Fed. Cir. 2015), which affirmed the invalidation of the broader claims and reversed on the dependent claims, finding those invalid too.

Several other post-grant appeals are still pending, including those addressing the Board’s power to invoke the “redundancy” doctrine and the Board’s power to “join” additional claims raised in a second IPR petition filed by the same party. Most Appellants will be hard-pressed to find a legal issue that makes their case stand out from the wave of others, while appellees will be content to blend in with the crowd.

- Zoll Lifecor Corporation v. Philips Electronics North America Corp. and Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. (IPR2013-00606)

- Atlanta Gas Light Company v. Bennett Regulator Guards, Inc., (IPR2013-00453)

- Chief Judge James Donald Smith, USPTO Discusses Key Aspects of New Administrative Patent Trials, UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE, Apr. 4, 2012, www.uspto.gov/patent/laws-and-regulations/america-invents-act-aia/message-chief-judge-james-donald-smith-board

- The Taylor factors include: (1) whether third party agrees to be bound by the Board’s determination; (2) whether a pre-existing relationship with the party named in the proceeding justifies binding the third party; (3) whether the third party is adequately represented by someone with the same interests; (4) whether the third party exercised or could have exercised control over the proceeding; (5) whether the third party is bound by a prior decision and is attempting to rehear the matter through a proxy; (6) whether a statutory scheme forecloses successive hearing by third parties. 77 Fed. Reg. 48759 (citing Taylor v. Sturgell, 553 U.S. 880 (2008))

- Zoll Lifecor Corporation v. Philips Electronics North America Corp. and Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V., (IPR2013-00606)

- Unified Patents Inc. v. Dragon Intellectual Property, LLC, (IPR2014-01252); Petroleum Geo-Services Inc. v. WesternGeco LLC, (IPR2014-00688)

- RPX Corporation v. Virnetx Inc., (IPR2014-00171, IPR2014-00172, IPR2014-00173, IPR2014-00174, IPR2014-00175, IPR2014-00176, IPR2014-00177)

- 35 U.S.C. § 325(d)

- ZTE Corp. v. ContentGuard Holdings, Inc., (IPR2013-00454); Unilever, Inc. v. Procter & Gamble Co., (IPR2014-00506); Medtronic, Inc. v. Nuvasive, Inc., (IPR2014-00487)

- ZTE Corp. v. ContentGuard Holdings, Inc., (IPR2013-00454)

- Intelligent Bio-Systems, Inc. v. Illumina Cambridge Limited, (IPR2013-00324)

- Medtronic, Inc. v. Robert Bosch Healthcare Systems, Inc., (IPR2014-00436)

- Unified Patents v Personal Web, (IPR2014-00702)

- Prism Pharma Co., Ltd. v. Choongwae Pharma Corp., (IPR2014-00315)

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.