Article

Why PTAB 'Step 2B' Reversal Rates Are Falling

Law360

Authors

-

- Name

- Michael P. Shepherd

- Person title

- Principal

Principal Michael Shepherd authored Expert Analysis for Law360 examining the declining reversal rate on Step 2B of subject matter eligibility rejections at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, hypothesizing how a shift in standards caused this occurrence and offering solutions to address the problem.

Read the full article on Law360.

Something surprising has happened with the way the Patent Trial and Appeal Board is deciding ex parte appeals of subject matter eligibility rejections under Section 101 of the Patent Act. Namely, reversals have become vanishingly rare on the second half, the so-called Step 2B part, of the analysis.

As of the first week of November, the reversal rate on Step 2B was at a five-year low — and falling.

This result is especially surprising in light of the 2018 Berkheimer v. HP Inc. decision in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, and corresponding guidance issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office — the Berkheimer Memo — which required examiners to support rejections under Step 2B with explicit fact finding.

Thus, on its face, the Berkheimer Memo seemed to raise the bar for examiners to establish and support a rejection under Step 2B and consequently seemed to enlarge the opportunities for applicants to obtain a reversal at the PTAB on Step 2B.

Yet exactly the opposite has happened. Instead of becoming easier, winning a reversal on Step 2B at the PTAB has never been more unlikely.

This article will first present data and statistics to illustrate this dramatic and ever-declining reversal rate on Step 2B. It will then present a hypothesis on how a behind-the-scenes shift in standards caused this to occur. Finally, it will offer suggested solutions to address this problem.

For the uninitiated, the U.S. Supreme Court in the 2012 Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories Inc. decision and the 2014 Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International decision established a two-step test to decide whether a claim is directed to patent-eligible subject matter.

Under Alice Step 1, the claim is evaluated to determine whether it is directed to an ineligible concept, e.g., an abstract idea or natural phenomenon.

If so, under Alice Step 2, the claim is evaluated to determine whether it contains an inventive concept sufficient to ensure that the claim is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the ineligible concept.

The USPTO has different nomenclature for these steps, with Alice Step 1 being referred to as Step 2A, and Alice Step 2 being referred to as Step 2B.

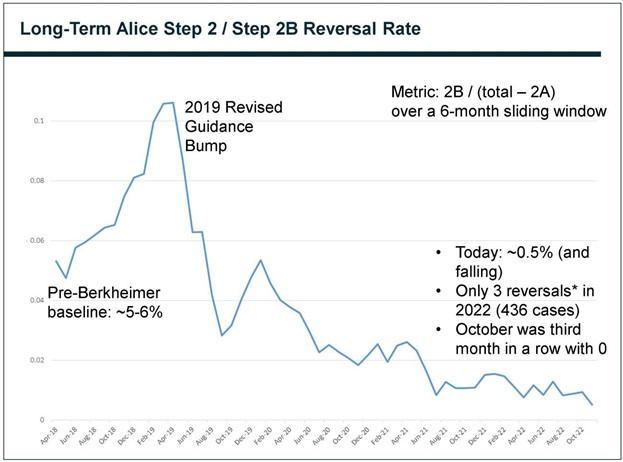

Figure 1 illustrates the long-term Alice Step 2 — Step 2B reversal rates, based on an extensive review of the most recent 6,125 published PTAB decisions that involved a Section 101 rejection.

Figure 1 thus incorporates the result of every published PTAB Section 101 decision between Nov. 1, 2017 and Nov. 8, 2022.

Figure 1

As shown on the left-hand side of Figure 1, in the six months leading up to the Berkheimer Memo — Nov. 2017 to April 2018 — the Step 2B reversal rate held steady at about 5% to 6% of all Section 101 appeals. Thus, roughly 1 in 20 appeals were reversed on Alice Step 2.

In January 2019, there was a surge in reversals due to the USPTO issuing new Section 101 guidance —the “2019 Revised Guidance” — that incorporated the directives of the Berkheimer Memo.

But since May 2021, Step 2B reversals have become rare. In 832 decisions, there have been only 7 reversals on Step 2B in that time frame.

October 2022 was the third full month in a row with zero Step 2B reversals, and in the 14 decisions since November 1, 2022, there have also been zero.

Thus, today, roughly 1 in 200 appeals are reversed on Step 2B.

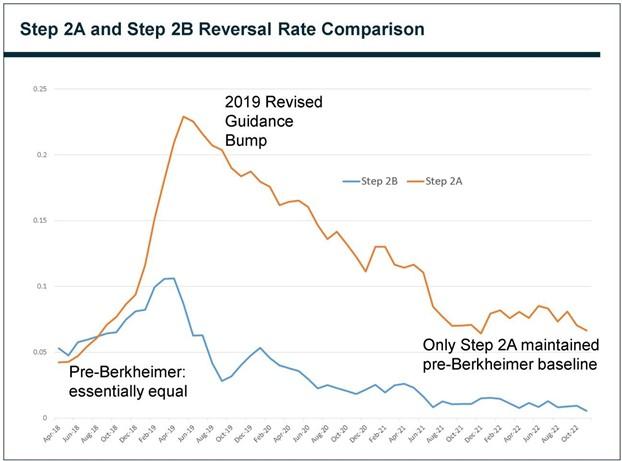

This dramatic downward trend did not occur for Alice Step 1/Step 2A reversals. Figure 2 illustrates historical Step 2A reversal rates compared with Step 2B reversal rates.

Figure 2

Notably, reversals on both steps were essentially equally likely before the Berkheimer Memo. Both steps also received significant increases in reversals due to the 2019 Revised Guidance. Yet in recent months, only Step 2A has maintained a rate resembling the pre- Berkheimer baseline.

How did this happen?

After an extensive review of these cases, a prime suspect has emerged: The increasingly widespread adoption of a shortcut that allows the PTAB to bypass any real fact-finding to hand the examiner a win on Step 2B every time.

In a sense, the PTAB has replaced the prescribed “search for an inventive concept” and fact finding analysis with a circular test that the examiner can never lose.

I call this shortcut the “Bifurcated Additional Elements Test”: in which elements of a claim are bifurcated into (1) things “belonging to” the abstract idea, and (2) generic computing components.

The trick is that only the generic computing components are evaluated on Step 2B, where the dispute is primarily over whether the claim includes any unconventional features.

But the practice of separating out conventional computing equipment for the purpose of evaluating whether the conventional computing equipment includes anything unconventional is purely circular reasoning.

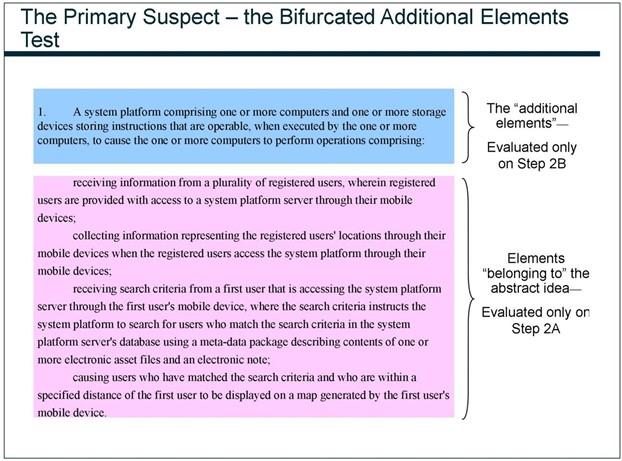

Figure 3 illustrates how this shortcut works on a hypothetical claim.

Figure 3

Central to this shortcut is the incorrect insistence by the PTAB that none of the elements in the pink box can be considered on Step 2B.

This example claim intentionally includes a few elements in the pink box “using a meta-data package,” “one or more electronic asset files,” and “an electronic note,” whose inventive or conventional or unconventional nature is not immediately apparent without factual findings as required by the Berkheimer Memo.

But here’s the trick: by limiting the Step 2B analysis to the conventional computing equipment in the blue box, the PTAB doesn’t need to worry about any of those factual disputes.

Instead, they simply focus their Step 2B analysis on how generic computers cannot supply an inventive concept. Thus, by initially splicing up the claim in this way, the PTAB guarantees a Step 2B affirmance every time.

In the briefing between applicants and examiners, the parties often can’t seem to agree not only on what the rules are, but on what game is even being played.

A typical scenario proceeds as follows: In the appeal brief, the applicant writes pages upon pages of arguments about which claim features provide an inventive concept under Step 2B.

But the examiner sidesteps all of that entirely and simply says that the only thing that matters on Step 2B is the generic computing equipment, which is self-evidently conventional.

In the reply brief, the applicant responds by writing pages upon pages about how the examiner’s conclusory analysis — often just a single paragraph — does not even come close to satisfying the rigorous fact-finding requirements mandated by the Berkheimer Memo and enshrined in the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure.

But then, the PTAB’s decision summarily affirms the examiner by simply stating that generic computing equipment is, in fact, conventional. The examiner wins again, without any of the substantive or procedural points raised by the applicant’s briefs being addressed or refuted. And this is not an isolated or even a rare occurrence. Similar scenarios play out again and again in ex parte appeals involving Step 2B.

There are several reasons that the Bifurcated Additional Elements Test is wrong.

First, the test pure circular reasoning. By first separating out conventional computer components, the PTAB ensures that nothing unconventional will be found on Step 2B.

Second, the test has no authority. No memo, MPEP section, regulation, statute, or precedential court decision even suggests bifurcating claim elements in this way. Moreover, no authority says elements considered on Step 2A cannot also be considered on Step 2B.

Third, the MPEP states exactly the opposite. Regarding Step 2B, the MPEP states:

Evaluating additional elements to determine whether they amount to an inventive concept requires considering them both individually and in combination to ensure that they amount to significantly more than the judicial exception itself. Because this approach considers all claim elements, the Supreme Court has noted that ‘it is consistent with the general rule that patent claims “must be considered as a whole.”[1]

Fourth, the Federal Circuit confirmed recently that claims can have an inventive concept even when all the hardware is generic.

In the Sept. 28 Cooperative Entertainment Inc. v. Kollective Technology Inc. decision, the Federal Circuit, wrote that “useful improvements to computer networks are patentable regardless of whether the network is comprised of standard computing equipment.”

This is an important point because many of our most cutting-edge inventions today are implemented using generic computers, including those relating to artificial intelligence and blockchain systems.

And in fact, the USPTO has publicly committed to incentivizing patent protection of these technologies.

Fifth, the Federal Circuit has also criticized bifurcating claim elements into different steps of the eligibility analysis. For example, in the 2020 Gree v. SuperCell the court said:

To the extent that the Board meant that a proper § 101 analysis may consider some claim limitations only at Alice step one and others only at Alice step two, we do not agree with its reading of Supreme Court precedent. Instead, both steps of the Alice inquiry require that the claims be considered in their entirety.

The widespread adoption of this test, with its preordained outcome, has resulted in another surprising shift in how the PTAB decides cases on Step 2B.

Namely, the PTAB has stopped issuing substantive reversals. In the pre-Berkheimer era, essentially every Alice Step 2 reversal was substantive, meaning that the PTAB would determine that the appellant had established that the claims contain an inventive concept and reverse on that basis.

In contrast, it has now been more than two years since the PTAB has made such a determination. Instead, all reversals since then are Step 2B procedural reversals.

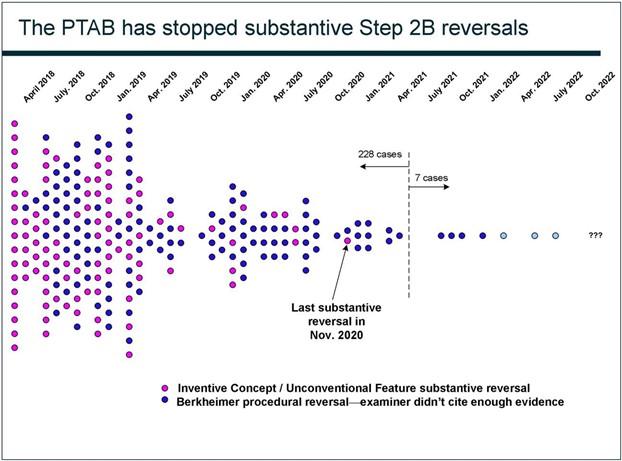

Figure 4 below illustrates every Alice Step 2/Step 2B reversal since March 2018 with a color- coded dot. Pink dots are substantive reversals, and blue dots are Berkheimer procedural reversals.

Figure 4

Figure 4 illustrates how substantive reversals dried up and were replaced entirely by Berkheimer procedural reversals. And as discussed above, now even the Berkheimer procedural reversals are drying up as well.

In other words, the Bifurcated Additional Elements Test has been so successful that it has eliminated all substantive reversals as they were known before Berkheimer as well as all procedural reversals afterwards.

The overall picture presented by Figure 4 is in remarkably stark contrast to what everyone thought the Berkheimer Memo was going to mean. Rather than providing expanded avenues for applicants to establish patent eligibility, the Berkheimer Memo is now largely toothless because the PTAB found a way to shortcut it with a circular test that the applicant loses every time.

What should be done to address this development? First, the office needs to issue updated guidance that unequivocally states that the Bifurcated Additional Elements Test is wrong.

Namely, guidance that (1) states that it is incorrect to separate out just the generic computing equipment for Step 2B, and (2) states that elements considered on Step 2A must also be considered on Step 2B.

The office might also consider reiterating to the PTAB that the MPEP’s guidance, on this and other points, is binding on them. When the PTAB takes shortcuts, and when it overlooks shortcuts taken by the examining corps, applicants and the public suffer an ever deeper drop in examination quality.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.

Blog March 14, 2025

Trump Nominates John Squires as USPTO Director: Here’s What to Watch

Article November 20, 2024

How a Second Trump Presidency Could Shape IP

Blog September 16, 2024

Federal Circuit Finds Conventional Components Can Provide a Technological Advantage at Alice Step 1

Blog July 19, 2024

USPTO Updates Eligibility Guidance on AI Inventions

Article June 13, 2024

AI and the Word That's Been Missing From Patent Eligibility Case Law

Blog June 2, 2025

Navigating Change at the USPTO

Blog May 23, 2025

John Squires Faces the Senate Judiciary Committee

Article May 9, 2025

Patent Diligence for VCs and PEs

Blog May 7, 2025

Federal Circuit Clarifies Limits of Patent Eligibility for Machine Learning Claims

Blog April 28, 2025

Can Clinical Trials Negate Patentability for Pharma Inventions?

Blog April 16, 2025

Key Insights From the UPC’s First SEP Decision

Blog March 18, 2025

Federal Circuit: PTE for Reissue Patents Should Be Calculated From Original Patent’s Issue Date

Blog March 14, 2025

Trump Nominates John Squires as USPTO Director: Here’s What to Watch

Blog February 18, 2025

How Startups Can Position Their IP Portfolios to Attract Investors

Blog January 21, 2025

How Standardization, SEPs, and Patent Pools Can Benefit the EV and Battery Industries