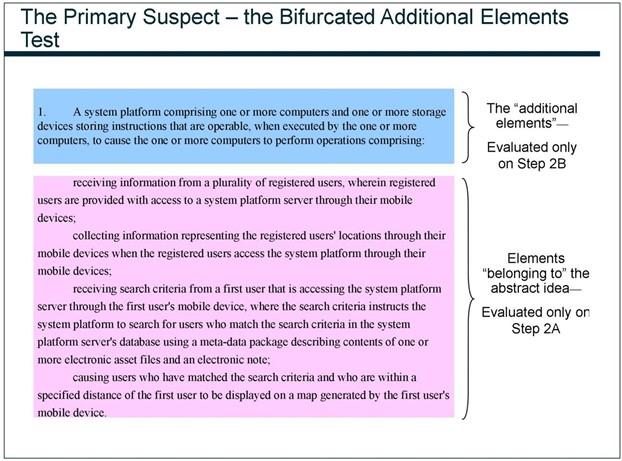

Central to this shortcut is the incorrect insistence by the PTAB that none of the elements in the pink box can be considered on Step 2B.

This example claim intentionally includes a few elements in the pink box “using a meta-data package,” “one or more electronic asset files,” and “an electronic note,” whose inventive or conventional or unconventional nature is not immediately apparent without factual findings as required by the Berkheimer Memo.

But here’s the trick: by limiting the Step 2B analysis to the conventional computing equipment in the blue box, the PTAB doesn’t need to worry about any of those factual disputes.

Instead, they simply focus their Step 2B analysis on how generic computers cannot supply an inventive concept. Thus, by initially splicing up the claim in this way, the PTAB guarantees a Step 2B affirmance every time.

In the briefing between applicants and examiners, the parties often can’t seem to agree not only on what the rules are, but on what game is even being played.

A typical scenario proceeds as follows: In the appeal brief, the applicant writes pages upon pages of arguments about which claim features provide an inventive concept under Step 2B.

But the examiner sidesteps all of that entirely and simply says that the only thing that matters on Step 2B is the generic computing equipment, which is self-evidently conventional.

In the reply brief, the applicant responds by writing pages upon pages about how the examiner’s conclusory analysis — often just a single paragraph — does not even come close to satisfying the rigorous fact-finding requirements mandated by the Berkheimer Memo and enshrined in the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure.

But then, the PTAB’s decision summarily affirms the examiner by simply stating that generic computing equipment is, in fact, conventional. The examiner wins again, without any of the substantive or procedural points raised by the applicant’s briefs being addressed or refuted. And this is not an isolated or even a rare occurrence. Similar scenarios play out again and again in ex parte appeals involving Step 2B.

There are several reasons that the Bifurcated Additional Elements Test is wrong.

First, the test pure circular reasoning. By first separating out conventional computer components, the PTAB ensures that nothing unconventional will be found on Step 2B.

Second, the test has no authority. No memo, MPEP section, regulation, statute, or precedential court decision even suggests bifurcating claim elements in this way. Moreover, no authority says elements considered on Step 2A cannot also be considered on Step 2B.

Third, the MPEP states exactly the opposite. Regarding Step 2B, the MPEP states:

Evaluating additional elements to determine whether they amount to an inventive concept requires considering them both individually and in combination to ensure that they amount to significantly more than the judicial exception itself. Because this approach considers all claim elements, the Supreme Court has noted that ‘it is consistent with the general rule that patent claims “must be considered as a whole.”[1]

Fourth, the Federal Circuit confirmed recently that claims can have an inventive concept even when all the hardware is generic.

In the Sept. 28 Cooperative Entertainment Inc. v. Kollective Technology Inc. decision, the Federal Circuit, wrote that “useful improvements to computer networks are patentable regardless of whether the network is comprised of standard computing equipment.”

This is an important point because many of our most cutting-edge inventions today are implemented using generic computers, including those relating to artificial intelligence and blockchain systems.

And in fact, the USPTO has publicly committed to incentivizing patent protection of these technologies.

Fifth, the Federal Circuit has also criticized bifurcating claim elements into different steps of the eligibility analysis. For example, in the 2020 Gree v. SuperCell the court said:

To the extent that the Board meant that a proper § 101 analysis may consider some claim limitations only at Alice step one and others only at Alice step two, we do not agree with its reading of Supreme Court precedent. Instead, both steps of the Alice inquiry require that the claims be considered in their entirety.

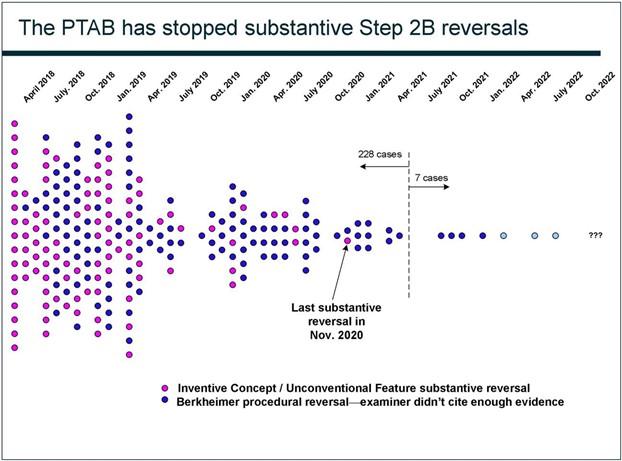

The widespread adoption of this test, with its preordained outcome, has resulted in another surprising shift in how the PTAB decides cases on Step 2B.

Namely, the PTAB has stopped issuing substantive reversals. In the pre-Berkheimer era, essentially every Alice Step 2 reversal was substantive, meaning that the PTAB would determine that the appellant had established that the claims contain an inventive concept and reverse on that basis.

In contrast, it has now been more than two years since the PTAB has made such a determination. Instead, all reversals since then are Step 2B procedural reversals.

Figure 4 below illustrates every Alice Step 2/Step 2B reversal since March 2018 with a color- coded dot. Pink dots are substantive reversals, and blue dots are Berkheimer procedural reversals.

Figure 4