Article

Biologic Patents Are Under Attack

Authors

-

- Name

- Person title

- Senior Principal

A bedrock principle of U.S. health care is that a strong patent system is critical to new drug development. Tufts University, which has tracked drug development costs for over a decade, estimates that it cost manufacturers $2.6 billion, on average, to bring a new drug to market in 2014 — up from just over $1 billion in 2003. President Obama's Council of Advisers on Science and Technology reports that it now takes 14 years, on average, to bring a new drug to market — up from about nine years just a few years ago. With patent protection for new drug discoveries fixed at 20 years, these statistics ominously warn drug manufactures that they will have increasingly less time to recoup increasingly more investment with each passing year. And this partially explains why drug prices, which are not regulated in the U.S., continue to rise as the market prices move in lockstep with the investment risk, just like any other commodity.

A second core principle of U.S. health care, in tension with the first, is the notion that drugs should be made available and affordable to everyone, which to a large extent most drugs are. Industry studies report that generic drugs today account for over 80 percent of prescriptions filled. To keep these bedrock principles in balance, however, requires a deft regulatory touch. If the balance is tipped too far in either direction, U.S. health care will suffer — investment capital will be diverted to less risky ventures or rising drug costs will overburden medical reimbursement systems.

The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act sought to impose a unique equilibrium on drug innovators and then-emerging generic manufacturers. First movers were rewarded with "market exclusivities" to ensure the recovery of their risk capital; a mechanism was established to facilitate the litigation of drug patents prior to generic entry; and copycat drugs would be approved quickly once those protections had lapsed. But Hatch-Waxman targeted mainly small molecule drugs that were regulated under the Food Drug & Cosmetic Act and which could be synthesized easily and manufactured cheaply. It did not address the emerging field of large molecule biologics that were regulated under the Public Health Service Act and made by living organisms and complex analytical processes. Because biologic drugs could not be copied or "manufactured" easily, manufacturers faced little competition and prices could be set by what the market would bear.

In 2010, that seemed destined to change with the passage of legislation that created an abbreviated approval pathway for "biosimilars" to compete against brand biologic drugs. Known as the Biologic Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), the new law was roughly modeled on Hatch-Waxman, with exclusivities provided for first movers and procedural rights for brand manufacturers to litigate their patents prior to biosimilar market entry.

At this writing, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved two biosimilar drugs — Zarixo, a biosimilar version of Amgen Inc.'s Neupogen, and Inflectra, a biosimilar version of Johnson & Johnson/Merck & Co. Inc.'s Remicade — with seven other applications currently pending. In both approvals, the "blocking" patents on the brand biologics had expired, leaving these multibillion dollar franchises essentially unprotected from competitive entry. However, many other biologics with even more lucrative revenue streams are protected by patent portfolios that have been strategically assembled to stave off such competition. Humira, for example, is an AbbVie Inc. drug approved to treat various autoimmune conditions that is fortified by more than 70 patents protecting the methods of treatment, formulations, manufacturing processes and related diagnostics. But times are changing and drug patents, particularly in the field of biologics, may no longer provide the bulletproof protections that manufacturers once thought they would.

One major change was congressional passage of the America Invents Act in 2011 (AIA) which opened a new administrative pathway, known as inter partes review (IPR) for anyone to challenge the validity of a patent without going to court. The institution of an IPR challenge can be consequential, as seen recently when a key Humira patent came under attack by a prospective biosimilar entrant and impacted the prices of both companies' stocks. Then, there has been the steady devaluation of method-of-use patents that protect multitherapy drugs, by state drug substitution laws that facilitate the sale and use of "skinny-labeled" generics for "off-label" uses. Once biosimilars are approved as "interchangeable" with the brand as intended by the BPCIA, state substitution laws may threaten to have a similar impact on brand biologics. Finally, recent case law suggests that many process patents considered vital to biologic drug production may be ineffective in stopping infringing activities or the importation of biosimilars from countries that do not share our patent culture. Collectively, these developments could spell trouble for some of the large biologic monopolies whose "salad days" may be coming to an end. For consumers and reimbursers, they signal a rebalancing of one segment of health care spending that is long overdue.

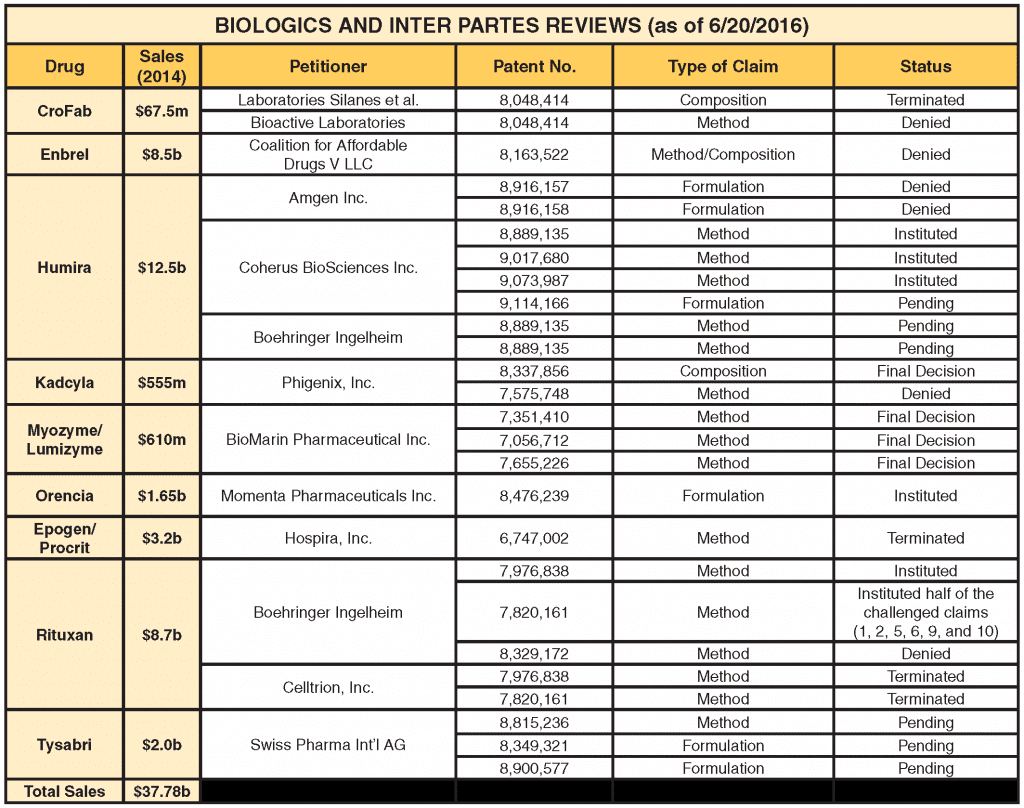

Inter Partes Review

The number of IPR petitions challenging drug patents has climbed steadily and now represents about 15 percent of all new IPR cases filed. Approximately half of these are instituted by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) for review, which is still below the norm for nondrug cases, which are instituted about 72 percent of the time. Small molecule drugs represent the lion's share of IPR challenges, but that may be changing as biologic drugs are increasingly under IPR attack as companies become familiar with the biosimilar approval process. As the following table shows, since 2013, nine biologic drugs representing approximately $38 billion in annual sales have been the target of IPR challenges by various petitioners.

What makes the IPR process such a desirable and effective weapon in a patent fight is the low cost and speed of resolution as compared to court litigation. Estimates vary, but an IPR usually can be prosecuted for less than a $1 million, in contrast to the $5 to $8 million that is typically required for a full blown patent litigation. In addition, an IPR must be instituted (or denied) within six months of filing and, if instituted, must be completed within 12 months; appeals go directly to the Federal Circuit. By comparison, a Hatch-Waxman litigation takes, on average, three to five years to complete. Most important, however, is the fact that drug patents can be attacked without the petitioner having an application on file with the FDA. Thus, the significant upfront cost of preparing and submitting a drug application can be deferred until the brand's key patents have been tested in an IPR proceeding.

Suddenly, brands are finding themselves under attack, sometimes by multiple competitors coming at them on different patents, all vying for a piece of the brand's lucrative monopoly. Even more daunting is that the challengers tend to be other brands who are financially well-heeled, patent savvy and know how to read the odds — since the doors were opened to IPRs in 2012, 84 percent of final PTAB decisions have invalidated at least some part of the challenged patent. And on June 20, 2016, the Supreme Court in Cuozzo upheld the Patent Office's "broadest reasonable interpretation" standard for construing patent claims during an IPR, making it easier to invalidate patents administratively than in a court of law.

Several petitioners appear to be using the IPR process as a type of "freedom to operate" strategy to clear out patents in the early stages so they do not become impediments when a biosimilar application is filed. In this way, the prospective biosimilar entrant can dispose of key patents that may become the focus of the "patent dance" (the information exchange under the BPCIA that can lead to the first wave of patent litigation) or involved in the second wave of prelaunch litigation contemplated by the BPCIA. In the case of Humira, the second top selling drug in the U.S. and responsible for 60 percent of AbbVie's annual revenues, the institution of an IPR on what some considered to be a foundational patent revealed an unexpected weakness in the portfolio. By the next day, AbbVie's stock was down 4.7 percent. Bloomberg talked about the AbbVie "patent dam springing a leak" while other investment advisors worried aloud over a possible "domino effect" with other patents.

Biologic Use and Process Patents

Biologic drugs are complex macromolecules made by living organisms whose chemical and physical properties are, often times, not fully understood. As a result, biologic manufactures must rely on complex analytical processes and bioassays to maintain quality control over manufacturing, stability assessment and batch release. These activities are highly regulated by the FDA as a condition for marketing approval. To protect the biologic franchise, manufacturers amass patent portfolios that cover the approved composition, therapeutic uses and various processes required to manufacture a safe and effective drug product. However, once the composition patent(s) expires, the other patents in the portfolio are all that remain, and even when large in number, they may come up short in protecting against biosimilar entry. Method of use patents can be avoided by labeling strategies, and certain process patents may be unenforceable under the Hatch-Waxman "safe harbor" or when practiced in foreign countries that may be beyond the reach of U.S. law.

Therapeutic Use Patents

Consider the case of a hypothetical brand biologic that is protected by several therapeutic use patents that expire on different dates (Humira, for example, is approved for seven indications protected by 22 patents that expire on different dates over a nine year period). A biosimilar entrant runs BPCIA-required "similarity" studies on the therapeutic indication that is the most expedient for obtaining FDA approval. At the same time, it provides a scientific justification to "extrapolate" those studies to the other uses approved for the brand biologic, a novel practice permitted under the BPCIA to avoid the high cost and time delays that would accompany a requirement to run studies on all of the brand biologic's approved uses. Once the prospective entrant secures FDA approval, it can launch its biosimilar labeled only for uses not protected by patent, as also permitted by the BPCIA.

Though the biosimilar goes to market with a "skinny label," the manufacture can bank on the common practice of "off-label" prescribing by physicians who are familiar with the therapeutic uses on the brand label and may be willing to prescribe a low cost alternative. The brand's use patents may end up being unenforceable against the biosimilar manufacturer because the on-label use does not infringe. Moreover, if the biosimilar drug is subsequently approved by the FDA as "interchangeable" as the BPCIA allows, pharmacists and benefits managers may be allowed to substitute it automatically for the brand biologic without need for physician consent.

Although the FDA has not yet determined how it will implement the BPCIA's interchangeability provisions, if it follows the model it established decades ago for small molecule drugs, a designation of interchangeability may follow the drug rather than the labeled indications. In the end, brand manufactures may find that method-of-use patents offer less protection against biosimilar entry than they may have thought.

Process Patents Ancillary to Manufacturing

As noted above, post-production quality control and lot-based release testing are required for most biologic drugs. Often times, these manufacturing steps involve complex analytical processes that are expensive to develop and therefore patent-protected. Under the BPCIA, a biosimilar drug must be "highly similar" to the brand biologic and have no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity and potency. A determination as to whether a biosimilar candidate meets these standards may often require the use of patented processes or assays to identify certain physical characteristics or biomarkers. How well these patents protect the brand biologic, especially when they are ancillary to manufacturing, is an issue undergoing litigation in a case involving the biologic drug, Lovenox (enoxaparin).

Momenta Pharmaceuticals Inc., the manufacturer of Lovenox, holds a patent on the official United States Pharmacopeia-specified testing method for determining bioequivalence on a batch-by-batch basis for generic versions of enoxaparin. Following FDA approval of an Amphastar Pharmaceuticals Inc. version of enoxaparin, Momenta sued for infringement on the basis that its process patent would have had to be practiced to perform the required bioequivalence testing for each batch of enoxaparin produced. One of the questions raised in the litigation was whether the Hatch-Waxman "safe harbor" protects against the infringement of a patented process used to maintain FDA approval in which records of the process are required to be kept but only submitted upon FDA request.

The matter came before the Federal Circuit on two occasions, in preliminary injunction and summary judgment phases, and the court reached different conclusions in each. In Momenta I, the Federal Circuit remanded the case to the district court, stating that bioequivalence testing "falls squarely within the scope of the safe harbor" provisions of Hatch-Waxman, as it generates information for submission to the FDA. The Federal Circuit determined that compliance with the bioequivalence testing requirements was "solely" for purposes "reasonably related" to the submission of information to the FDA. On remand, the district court entered summary judgment of noninfringement in favor of Amphastar.

In Momenta II, however, the Federal Circuit reevaluated whether post-approval studies fall within the safe harbor based on whether such uses are "reasonably related" to an actual "submission." Because previous decisions had determined that the safe harbor does not apply to "routine" post-approval reports to the FDA, the court reasoned that quality control testing for each batch meets the definition of "routine" and, therefore, is not "reasonably related to the development and submission of information to the FDA." In addition, Momenta II looked at whether quality control testing constitutes "made by" and thus subjects an imported product to the section 271(g) prohibition on products "made by" a process patented in the U.S. The court determined that final testing does not constitute "made by" and that process patents ancillary to "making" the product are not protected under section 271(g).

The issues raised in Momenta II are currently on petition for certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court. In the meantime, the protections afforded by certain types of process patents will be in a state of flux. If the Supreme Court grants certiorari and reverses the Federal Circuit on the safe harbor issue, process patents used to generate information required to maintain FDA approval may be unenforceable. But even if the Federal Circuit is upheld, patents that relate only to quality control, testing and analysis, as opposed to actual manufacturing of a finished or intermediate product, may escape the reach of 271(g) if they are practiced in countries where they cannot be enforced. In either case, many types of process patents that are important to biologic drug production will be put in jeopardy.

Conclusion

Biologic drug manufacturers are facing a confluence of disparate forces chipping away at once formidable patent estates. Novel IPR proceedings now offer a fast and relatively low cost means to challenge validity; method of use patents may be circumvented by skinny labeled biosimilars relying on state substitution laws developed under Hatch-Waxman to facilitate "off-label" use; and many processes required for biologic production and control may be falling through loopholes in the patent laws. Although biosimilar entrants stand to benefit directly from these pressures on their brand counterparts, it is the public that has the most to gain by the emergence of a competitive market for biologic medicines.

This article appeared on Law360 on June 29, 2016 and is reprinted with permission. To download a PDF version of this article, please click here.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors on the date noted above and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fish & Richardson P.C., any other of its lawyers, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This post is for general information purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is formed.